Abstract

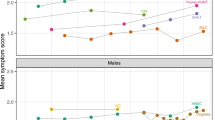

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen a rise in anxiety and depression among adolescents. This study aimed to investigate the longitudinal associations between sleep and mental health among a large sample of Australian adolescents and examine whether healthy sleep patterns were protective of mental health in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. We used three waves of longitudinal control group data from the Health4Life cluster-randomized trial (N = 2781, baseline Mage = 12.6, SD = 0.51; 47% boys and 1.4% ‘prefer not to say’). Latent class growth analyses across the 2 years period identified four trajectories of depressive symptoms: low-stable (64.3%), average-increasing (19.2%), high-decreasing (7.1%), moderate-increasing (9.4%), and three anxiety symptom trajectories: low-stable (74.8%), average-increasing (11.6%), high-decreasing (13.6%). We compared the trajectories on sociodemographic and sleep characteristics. Adolescents in low-risk trajectories were more likely to be boys and to report shorter sleep latency and wake after sleep onset, longer sleep duration, less sleepiness, and earlier chronotype. Where mental health improved or worsened, sleep patterns changed in the same direction. The subgroups analyses uncovered two important findings: (1) the majority of adolescents in the sample maintained good mental health and sleep habits (low-stable trajectories), (2) adolescents with worsening mental health also reported worsening sleep patterns and vice versa in the improving mental health trajectories. These distinct patterns of sleep and mental health would not be seen using mean-centred statistical approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental disorders are the leading cause of disability among young people aged up to 24 years worldwide, accounting for one quarter of all years lived with disability1. In Australia, mental disorders make up three of the five leading causes of burden of disease among those aged 12–24 years2 and cost the economy approximately $200–220 billion yearly3. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused disruptions to all facets of adolescent development and exacerbated mental health issues such as depression, anxiety and self harm4,5,6,7. Examining modifiable factors that were protective of mental health throughout this global crisis can offer insights on targets for prevention and early intervention, especially since improving the mental health of young people is a critical public health priority8.

There is growing evidence that sleep is a key modifiable factor associated with mental health9,10,11,12,13,14. Human sleep is primarily under biological control, governed by the well-supported two-process model of sleep15,16. The first process is sleep homeostatis, whereby pressure to sleep builds across the waking day and evening and dissipates during sleep. As adolescents develop, their ability to build sleep pressure in the evening declines, resulting in increased alertness in the evening. This inevitably results in a delay in the onset of sleep (i.e., a longer sleep onset latency)16. The second process—the circadian rhythm—is a cycle of sleep and wake across the 24 h day, and is of particular relevance during adolescence. From about age 10 to 20 years, the timing of the circadian rhythm delays, resulting in a later onset of sleep in the evening, and a later rise time (when allowed to sleep-in)16. However, 5 out of 7 days of the week, adolescents are prevented from slee** at their natural circadian times as they need to wake relatively early to prepare for, travel to, and attend school17. This inevitably results in a restriction of sleep across the school week (i.e., shortened total sleep time) and weekend catch-up, which leads to irregular sleep and pepetuates weekday sleep debt17.

Multiple studies have shown that poor sleep during paediatric development can increase the odds of develo** anxiety and depression, with two mechanisms implicated9. First, the restriction of sleep (less total sleep time) has been shown to dampen positive mood and hinder one’s next-day emotion regulation9. Second, an extended sleep onset latency is proposed to create an ideal environment for repetitive negative thinking (i.e., worry and rumination), which has been linked to both depression and anxiety in young people. An extended sleep onset latency is common among later chronotypes, which may be a predisposing factor for the development of depression and anxiety symptoms18. Conversely, a healthy sleep profile (particularly short sleep onset latency—between 5 and 30 min19, sufficient total sleep time—between 8 and 10 h20, and less daytime sleepiness) is associated with increased mental resilience (i.e., lower symptoms of anxiety and depression)21,22. Therefore, sleep is an important risk-/protective factor for the development of mental ill-health.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, mental resilience was tested on a global scale, and many adolescents experienced heightened psychopathology4,5,6,7. Sleep was also impacted, potentially relating to heightened stress and restrictions on movement and closure of schools; however, evidence as to whether healthy sleep improved or worsened has been mixed23,24,25. Surprisingly, one longitudinal study found that the prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep problems was higher before, compared to during and after, the pandemic26. While studies focusing on average changes are informative, they might miss for whom changes occur. Did all adolescents experience worse sleep and mental health? Were adolescents with healthy sleep patterns more resilient? For example, later chronotype26,37. Nonetheless, it might still be difficult to identify these emerging risk-groups (average-increasing trajectories), as their sleep was significantly different from the low-stable trajectories but it was not yet problematic (e.g., sleep duration close to the recommended 8 h/night20; see Tables 4, 5). This supports the importance of promoting sleep health in the adolescent population in a universal manner, as some of the adolescents at-risk might easily be missed. Given that the link between sleep and mental health is ultimately bi-directional and can create a vicious cycle of poor emotional regulation and poor sleep quality and quantity38, breaking this cycle by targeting sleep is warranted and has shown promising benefits for mental health9. For example, sleep has shown significant improvements (sleep onset latency in particular) alongside symptoms of depression following bright light therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), school-based sleep interventions9, and later school-start times39. Two recent meta-analyses found evidence that improving sleep can lead to an improvement in both anxiety and depressive symptoms40,41. In addition, addressing sleep problems first can be advantageous because it is less stigmatized and easier to talk about compared to mental health40.

The present study has a number of strengths and limitations that need to be taken into account when interpreting the results. Mental health symptoms and sleep patterns were self-reported, which can be subject to error and common method bias. However, externally developed measures that have been validated in adolescents were used. Although objective sleep measures are encouraged in future studies, self-reported sleep has proven valid compared to actigraphy42,43. This is also a more feasible method when including a large sample of adolescents followed over time. The large and diverse sample, spanning three Australian states is a strength of the study, together with the longitudinal design, which enabled to capture changes throughout the pandemic. Despite the three waves of longitudinal data, the results of this study cannot discern whether sleep patterns or mental health precede one another. More frequent longitudinal sampling could have provided a clearer picture44. However, using sophisticated person-oriented analyses allowed to highlight that not all adolescents were impacted the same way during the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, the majority of the sample coped well during this stressful time (low-stable trajectories) and these low-risk classes also reported the healthiest sleep patterns. In addition, although WASO and SOL decreased over time in the whole sample, when looking at subgroups the decrease occurred only among adolescents whose symptoms improved. These important results might have been missed if only average changes were examined.

To conclude, sleep and mental health go hand-in-hand for adolescents. During a stressful time such as the COVID-19 pandemic, good sleep health was distinctive of adolescents who maintained low and stable symptoms of anxiety and depression. Given the bidirectional nature of the link between sleep and mental health, promoting healthy sleep habits in adolescents is a promising modifiable factor to improve and maintain mental health. Adolescent mental health is a public health priority8, and this study provides empirical evidence that sleep health should be one central target for prevention and intervention.

Method

Design and participants

This study utilises data from the “Health4Life” cluster randomised controlled trial, which aimed to evaluate the efficacy of an eHealth intervention targeting six modifiable risk factors among Australian adolescents (sleep, physical activity, diet, screen time, alcohol use and tobacco smoking). Baseline data were collected in 2019 (approximately July-November) using online self-report surveys among Year 7 students at 71 secondary schools across New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (QLD) and Western Australia (WA), with follow up surveys conducted in 2020 (approximately July-December) and 2021 (approximately July-December). To avoid contamination effects from the intervention, this study focuses on control group data. Only students with data on depressive and anxiety symptoms at baseline were included (Depressive symptom trajectories: NT1 = 2781, NT2 = 2280, NT3 = 2095; Anxiety symptom trajectories: NT1 = 2781, NT2 = 2267, NT3 = 2088). Participants provided written consent and parents provided passive, active written or active verbal consent, depending on the approved procedures for the school/region. The Health4Life trial was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, it was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials registry (ACTRN12619000431123) and has ethical approval from ten relevant committees (University of Sydney HREC2018/882, NSW Department of Education SERAP 2019006, University of Queensland 2019000037, Curtin University HRE2019-0083 and several Catholic Diocese committees). The study protocol provides further details on recruitment and consent procedures29.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic factors included sex assigned at birth, age, cultural and linguistic diversity (CALD), and relative socioeconomic position. CALD was defined as per recommendations from a recent Australian review45 to include participants who were born in a non-English speaking country and/or primarily speak a language other than English at home. Relative family affluence was identified using the Family Affluence Scale III (FASIII), which has demonstrated good test–retest reliability (r = 0.90) and strong correlation with parental report46. The FASIII generates a summed score across indicators of familial wealth (e.g., number of computers, number of bathrooms in home, etc.) as a proxy for familial socioeconomic status that children and adolescents might be better at reporting compared to parent or caregivers’ income and education.

Sleep patterns

Average sleep duration per night was measured using the validated Modified Sleep Habits Survey42,43. Students reported the time they usually: (1) went to bed (time—12 h format), (2) attempted sleep (time—12 h format), (3) took to fall asleep (duration—h, min), (4) were awake during the night (duration—h, min), and 5() woke up in the morning (time—12 h format) over the past week (separately for week nights and weekend nights). In the present study, we derived several sleep parameters, including sleep onset latency (SOL; i.e., time taken to fall asleep), wake after sleep onset (WASO; i.e., time awake during the night), total sleep time (TST; i.e., time between falling asleep and wake up in the morning, minus WASO) during schooldays, and chronotype. We calculated chronotype as the midpoint of sleep on free days (i.e., sleep onset time on weekends plus sleep duration on weekends, divided by 2). According to Roenneberg et al.47 a correction needs to be made as many adolescents restrict their sleep on schooldays and attempt to catch up on weekends. Therefore, if the sleep duration on weekends is longer than on schooldays, sleep midpoint is calculated as sleep onset time (weekends) plus sleep duration (average schoolday-weekend) divided by 2. The midpoint of sleep is a good behavioural marker for circadian phase47. Finally, to examine irregular sleep patterns during weekdays and weekends, we calculated “weekend sleep-in” by subtracting wake-up time on weekends—wake-up time on weekdays48.

Sleepiness

The Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale was used to assess daytime sleepiness30. It has been validated in adolescents and includes eight items such as ‘How often do you fall asleep or feel drowsy in class?’ and ‘How often do you have trouble getting out of bed in the morning?’ with five response options from ‘Never’ (0) to ‘Very often/ always’ (4), with scores ranging from 0 to 32. The cutoff for excessive sleepiness is 14 for boys and 17 for girls30. The Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable (α = 0.72).

Anxiety

Past 7-day anxiety symptoms were assessed with the PROMIS Anxiety Paediatric (PROMIS-AP) scale, which has been validated among adolescents49. The 13-item scale asks participants to report frequency of symptoms including difficulty relaxing, and feelings of nervousness, worry, and fear, amongst others on a scale from ‘never’ (1) to ‘almost always’ (5), the total ranging from 13–6549. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94.

Depression

Past 7-day depressive symptoms were measured using the modified Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents scale (PHQ-A)50. The 9-item scale asks participants to report how often they experienced symptoms such as “feeling down, depressed, irritable or hopeless”, sleep issues, tiredness, and changes in appetite, weight or behaviours on a scale from ‘not at all’ (0) to ‘nearly every day’ (3)50. The 9th item (measuring thoughts of death and self-harm) was removed on request of the ethics board. In addition, 2 items were excluded from analyses because of their overlap with sleep, our variable of interest. Depression symptoms were analysed using a sum of the remaining six items, ranging from 0–18 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84).

Data analysis

We followed a two-step procedure to identify different mental health trajectories51. In Step 1, we estimated a latent curve growth model to examine how, on average, adolescents’ mental health symptoms changed over a 2 years period, and to examine whether there was a significant between-person variation in intercept (initial level) and slope (change over time) of depression and anxiety. In Step 2, we used latent class growth analysis (LCGA) to identify adolescents with different mental health trajectories. To determine the number of trajectories that best fit the data we looked for the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), highest entropy (i.e., classification accuracy), non-significant Lo–Mendell–Rubin test (LMR; i.e., model fit improvement from n − 1 to n classes), and the proportion of adolescents in each group trajectory (> 5%)52. When these indicators were contrasting, we chose the most parsimonious solution (i.e., fewer classes)52. We analyzed trajectories for depressive symptoms and anxiety separately. To validate the distinctiveness of the classes, we compared depression and anxiety symptom trajectories on symptom levels at each time point using ANOVAs. After establishing the different trajectories, we compared adolescents in each trajectory on sex distribution and sleep parameters across three time points using the BCH method in Mplus53. This method uses a weighted multiple group analysis, where the groups correspond to the latent classes, and therefore the classes established in the LCGA model are not affected in this second step (i.e., when analysing differences in sleep patterns)53. Data were analysed in SPSS (v. 26) and Mplus54. We handled missing data in Mplus using full information maximum likelihood (FIML). Depressive symptoms model: 4 missing data patterns, covariance coverage ranged between 0.67 and 1.00. Anxiety model: 4 missing data patterns, covariance coverage ranged between 0.67 and 1.00. The covariance coverage was well above the recommended 0.10 to reliably use FIML. Moreover, FIML is a superior method compared to mean imputation, listwise deletion or pairwise deletion, as it provides more reliable standard errors55.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the agreement made with the individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Erskine, H. E. et al. A heavy burden on young minds: the global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychol. Med. 45(7), 1551–1563 (2015).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health of Young People. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/health-of-young-people (2020).

Australian Government Productivity Commission. Mental Health. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report (2020).

Viner, R. et al. School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 176(4), 400–409 (2022).

Samji, H. et al. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth – A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 27(2), 173–189 (2022).

Madigan, S. et al. Changes in depression and anxiety among children and adolescents from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 177(6), 567–581 (2023).

Bower, M. et al. A hidden pandemic? An umbrella review of global evidence on mental health in the time of COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1664–2640. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1107560 (2023).

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO-UNICEF Hel** Adolescents Thrive Initiative. https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/promotion-prevention/who-unicef-hel**-adolescents-thrive-programme (2023).

Gradisar, M. et al. Sleep’s role in the development and resolution of adolescent depression. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 512–523 (2022).

Jamieson, D., Broadhouse, K. M., Lagopoulos, J. & Hermens, D. F. Investigating the links between adolescent sleep deprivation, fronto-limbic connectivity and the onset of mental disorders: A review of the literature. Sleep Med. 66, 61–67 (2020).

Jamieson, D., Shan, Z., Lagopoulos, J. & Hermens, D. F. The role of adolescent sleep quality in the development of anxiety disorders: A neurobiologically-informed model. Sleep Med. Rev. 59, 101450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101450 (2021).

Lovato, N. L. & Gradisar, M. A. Meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep depression in adolescents: Recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med. Rev. 18, 521–529 (2014).

Marino, C. et al. Association between disturbed sleep and depression in children and youths: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. JAMA Netw. Open 4(3), e212373. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.2373 (2021).

Short, M. A., Gradisar, M., Lack, L. C. & Wright, H. R. The impact of sleep on adolescent depressed mood, alertness and academic performance. J. Adolesc. 36(6), 1025–1033 (2013).

Leger, D., Beck, F., Richard, J. B. & Godeau, E. Total sleep time severely drops during adolescence. PLoS One 7(10), e45204. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0045204 (2012).

Hagenauer, M. H. & Lee, T. M. Adolescent sleep patterns in humans and laboratory animals. Horm. Behav. 64(2), 270–279 (2013).

Crowley, S., Wolfson, A., Tarokh, L. & Carskadon, M. An update on adolescent sleep: new evidence informing the perfect storm model. J. Adolesc. 67, 55–65 (2018).

Bauducco, S., Richardson, C. & Gradisar, M. Chronotype, circadian rhythms and mood. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 34, 77–83 (2020).

Ohayon, M. et al. National sleep foundation’s sleep quality recommendations: First report. Sleep Health 3(1), 6–19 (2017).

Hirshkowitz, M. et al. National sleep foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 1(1), 40–43 (2015).

Yip, T. The effects of ethnic/racial discrimination and sleep quality on depressive symptoms and self-esteem trajectories among diverse adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 44, 419–430 (2015).

Orchard, F., Gregory, A. M., Gradisar, M. & Reynolds, S. Self-reported sleep patterns and quality amongst adolescents: Cross-sectional and prospective associations with aniety and depression. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiat. 61, 1126–1137 (2020).

Stone, J. E. et al. In-person vs home schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: Differences in sleep, circadian timing, and mood in early adolescence. J. Pineal Res. 71(2), e12757. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12757 (2021).

Olive, L. S. et al. Child and parent physical activity, sleep, and screen time during COVID-19 and associations with mental health: Implications for future psycho-cardiological disease?. Front. Psychiatry 12, 774858. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.774858 (2021).

Gardner, L. A. et al. Lifestyle risk behaviours among adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 12(6), e060309. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060309 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. How does the COVID-19 affect mental health and sleep among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal follow-up study. Sleep Med. 85, 246–258 (2021).

Zhao, J., Xu, J., He, Y. & **ang, M. Children and adolescents’ sleep patterns and their associations with mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Shanghai, China. J. Affect. Disorders 301, 337–344 (2022).

Bacaro, V. et al. The impact of COVID-19 on Italian adolescents’ sleep and its association with psychological factors. J. Sleep Res. 31(6), e13689 (2022).

Teesson, M. et al. Study protocol of the Health4Life initiative: A cluster randomised controlled trial of an eHealth school-based program targeting multiple lifestyle risk behaviours among young Australians. BMJ Open 10(7), e035662. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035662 (2020).

Drake, C. et al. The pediatric daytime sleepiness scale (PDSS): Sleep habits and school outcomes in middle-school children. Sleep 26(4), 455–458 (2003).

McLaughlin, K. A. & King, K. Developmental trajectories of anxiety and depression in early adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43, 311–323 (2015).

Wang, D. et al. Longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19 lockdown in China. J. Affect. Disord. 299, 628–635 (2022).

van Loon, A. W. et al. Trajectories of adolescent perceived stress and symptoms of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 15957. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20344-y (2022).

Smout, S., Gardner, L. A., Newton, N. & Champion, K. E. Dose-response associations between modifiable lifestyle behaviours and anxiety, depression and psychological distress symptoms in early adolescence. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 47(1), 100010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anzjph.2022.100010 (2023).

Short, M.A., Booth, S.A., Omar, O., Ostlundh, L., Arora, T. (2020) The relationship between sleep duration and mood in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews. 52, 101311; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101311.

Meltzer, L.J., et al. COVID-19 instructional approaches (in-person, online, hybrid), school start times, and sleep in over 5,000 U.S. adolescents. Sleep. 44(12), zsab180; https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab180 (2021).

Vidal Bustamante, C. M. et al. Within-person fluctuations in stressful life events, sleep, and anxiety and depression symptoms during adolescence: a multiwave prospective study. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiat. 61(10), 1116–1125 (2020).

Palmer, C. A. & Alfano, C. A. Sleep and emotion regulation: an organizing, integrative review. Sleep Med. Rev. 31, 6–16 (2017).

Mousavi, Z. & Troxel, W. M. Later school start times as a public health intervention to promote sleep health in adolescents. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 9, 152–160 (2023).

Gee, B. et al. The effect of non-pharmacological sleep interventions on depression symptoms: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 43, 118–128 (2019).

Staines, A. C., Broomfield, N., Pass, L., Orchard, F. & Bridges, J. Do non-pharmacological sleep interventions affect anxiety symptoms? A meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 31(1), e13451 (2022).

Wolfson, A. R. et al. Evidence for the validity of a sleep habits survey for adolescents. Sleep 2, 213–216 (2003).

Short, M. A., Gradisar, M., Lack, L. C., Wright, H. R. & Chatburn, A. Estimating adolescent sleep patterns: Parent reports versus adolescent self-report surveys, sleep diaries, and actigraphy. Nat. Sci. Sleep 5, 23–26 (2013).

Rynders, C. A. et al. A naturalistic actigraphic assessment of changes in adolescent sleep, light exposure, and activity before and during COVID-19. J. Biol. Rhythms 37(6), 690–699 (2022).

Pham, T. T. L. et al. Definitions of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD): A literature review of epidemiological research in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(2), 737 (2021).

Torsheim, T. et al. Psychometric validation of the revised family affluence scale: A latent variable approach. Child Indic. Res. 9(3), 771–784 (2016).

Roenneberg, T., Pilz, L. K., Zerbini, G. & Winnebeck, E. C. Chronotype and social jetlag: A (self-) critical review. Biology 8(3), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology8030054 (2019).

Gradisar, M. et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy plus bright light therapy for adolescent delayed sleep phase disorder. Sleep 34(12), 1671–1680 (2011).

Irwin, D. et al. An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Qual. Life Res. 19(4), 595–607 (2010).

Johnson, J. G., Harris, E. S., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J. Adolesc. Health 30(3), 196–204 (2002).

Jung, T. & Wickrama, K. A. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and personality psychology compass. 2(1), 302–317 (2008).

Weller, B. E., Bowen, N. K. & Faubert, S. J. Latent class analysis: A guide to best practice. J. Black Psychol. 46(4), 287–311 (2020).

Asparouhov, T. & Muthén, B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus Web Notes 21(2), 1–22 (2014).

Muthén, L.K., Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide. (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017).

Little, R. J. & Rubin, D. B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data 2nd edn. (Wiley, 2002).

Acknowledgements

The Health4Life study was led by researchers at the Matilda Centre at the University of Sydney, Curtin University, the University of Queensland, the University of Newcastle, Northwestern University, and UNSW Sydney: Teesson, M., Newton, N.C, Kay-Lambkin, F.J., Champion, K.E., Chapman, C., Thornton, L.K., Slade, T., Mills, K.L., Sunderland, M., Bauer, J.D., Parmenter, B.J., Spring, B., Lubans, D.R., Allsop, S.J., Hides, L., McBride, N.T., Barrett, E.L., Stapinski, L.A., Mewton, L., Birrell, L.E., & Quinn, C & Gardner, L.A.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Örebro University. The Health4Life study was funded by the Paul Ramsay Foundation and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council via Fellowships (KC, APP1120641; MT, APP1078407; and NN, APP1166377) and via a Centre of Research Excellence in the Prevention and Early Intervention in Mental Illness and Substance Use (PREMISE; APP11349009). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge all the research staff who have worked across the study, as well as the schools, students and teachers who participated in this research. The research team also acknowledges the assistance of the New South Wales Department of Education (SERAP 2019006), the Catholic Education Diocese of Bathurst, the Catholic Schools Office Diocese of Maitland-Newcastle, Edmund Rice Education Australia, the Brisbane Catholic Education Committee (373), and Catholic Education Western Australia (RP2019/07) for access to their schools to conduct this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.A.G., K.E.C., M.G., and S.B. conceived the idea behind the study. S.B. analysed the data. K.E.C., L.A.G., N.C.N. and M.T. acquired the fundings and coordinated data collection. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, writing, and reviewing the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Gradisar reports that he is the CEO of WINK Sleep Pty Ltd which provides professional training for the treatment of sleep disorders, and is employed by Sleep Cycle AB, a listed company whose app tracks sleep.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bauducco, S., Gardner, L.A., Smout, S. et al. Adolescents’ trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic and their association with healthy sleep patterns. Sci Rep 14, 10764 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60974-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60974-y

- Springer Nature Limited