Abstract

Coronaviruses have been the causative agent of three epidemics and pandemics in the past two decades, including the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. A broadly-neutralizing coronavirus therapeutic is desirable not only to prevent and treat COVID-19, but also to provide protection for high-risk populations against future emergent coronaviruses. As all coronaviruses use spike proteins on the viral surface to enter the host cells, and these spike proteins share sequence and structural homology, we set out to discover cross-reactive biologic agents targeting the spike protein to block viral entry. Through llama immunization campaigns, we have identified single domain antibodies (VHHs) that are cross-reactive against multiple emergent coronaviruses (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS). Importantly, a number of these antibodies show sub-nanomolar potency towards all SARS-like viruses including emergent CoV-2 variants. We identified nine distinct epitopes on the spike protein targeted by these VHHs. Further, by engineering VHHs targeting distinct, conserved epitopes into multi-valent formats, we significantly enhanced their neutralization potencies compared to the corresponding VHH cocktails. We believe this approach is ideally suited to address both emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants during the current pandemic as well as potential future pandemics caused by SARS-like coronaviruses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are a large family of viruses that infect numerous species, including humans, and consist of four main genera known as alpha, beta, gamma, and delta. The most significant CoV species, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a beta-coronavirus that emerged in China in 2019, is currently driving a pandemic that has resulted in over 500 million cases and 15 million excess deaths in the last 3 years1. Other strains of CoV include SARS-CoV and MERS, both of which have resulted in smaller, but significant, outbreaks with high morbidity and mortality.

Coronaviruses are single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) viruses with a large genome size and a relatively high mutation rate. Recombination events among different CoV species have been shown to occur, resulting in further genetic variability2. One of the key factors driving the continued large burden of COVID-19 disease is the observed high rate of mutation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, resulting in the emergence and rapid spread of novel viral variants capable of evading natural and vaccine-induced host immune responses. Based on systematic genomic sequencing of clinical isolates of SARS-COV-2, there are 12 lineage groups that have been identified and 5 of them, Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), Delta (B.1.617.2), and the newly identified Omicron (B.1.1.529), have been defined as variants of concern (VOCs) by the World Health Organization. The Omicron variant, bearing more than 30 mutations in the viral spike protein, is currently the major variant circulating globally. Multiple studies have reported resistance of the Omicron variant against neutralization by antibodies and serum targeting the wild type (Wuhan) strain, significantly impacting the protective efficacy of original licensed Wuhan strain based vaccines and therapeutic antibodies3,4,5,6. Bivalent mRNA vaccines including the original Wuhan based strain and the currently circulating Omicron BA.4/5 strain were recently made available as booster vaccines, however, it is possible that new VOCs will arise and escape again from these boosters’ induced immunity. Furthermore, the threat of continued zoonotic spillovers warrants the development of broadly reactive antiviral agents that could combat coronaviruses with pandemic potential in the future7.

While the vast majority of antibodies targeting the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein have been conventional immunoglobulins, several potent heavy-chain variable domains (VHHs) from camelid-derived single-domain antibodies (sdAbs) targeting the CoV-2 spike have also been reported8,9,10. Several cross-reactive epitopes on the spike have been identified in the literature, including Class 3 and Class 4 epitopes on the receptor binding domain (RBD), represented by S309 and CR3022, respectively11,12,13. Since VHHs are smaller compared to conventional antibodies (~ 15 kDa vs ~ 150 kDa), they have the potential to bind to smaller, conserved epitopes shared among different coronaviruses that conventional antibodies might not access. Moreover, VHHs have been shown to possess favorable biophysical properties and their smaller size also facilitates generation of multivalent constructs. In this work, we report the discovery of multiple VHHs that bind distinct cross-reactive epitopes on the spike protein. We further demonstrate that the neutralization potencies of multimeric VHHs are greatly enhanced compared to the monovalent forms. The enhanced potency and potential to protect against escape mutations make this approach valuable in addressing emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants as well as SARS-like viruses that may emerge in the future.

Results

Identification of cross-reactive VHHs

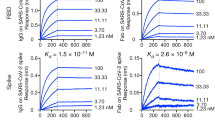

We used a heterologous immunization approach to identify VHHs with broad cross-reactivity (Fig. 1A). We hypothesized that cross-reactive B cells would be enriched after three rounds of immunizations with related, but non-identical spike proteins. To that end, llamas were first immunized with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, followed by spike proteins from MERS and SARS-CoV viruses with three-week intervals between the immunizations. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were harvested 10 days after the final immunization. B cells binding to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein were isolated and cultured, and supernatants were used to screen for binding to spike proteins from the three viruses. Twenty-three clones that bound to both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spikes were sequenced, recombinantly expressed in either monomeric or bivalent formats, and validated for binding by ELISA to soluble recombinant spike proteins (Fig. 1B, Table S1). The binding by the bivalent constructs was also assessed by flow cytometry using cells recombinantly expressing spike protein on their surface (Table S2). All 23 constructs bound with similar affinity to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 with significant affinity improvement observed in the bivalent format, likely due to increased avidity. Many bivalent VHHs showed affinity to SARS-CoV-2 spike, and affinity mostly remained unchanged for SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta. However, 8 of the candidates lost binding to the Omicron variants BA.1 and BA.2 (Table S1). In addition, one VHH (6A1) also bound to spike proteins from MERS and endemic beta human coronaviruses OC43 and HKU1 (Table S1). Direct affinity measurement against CoV-2 spike protein using Biacore (Fig. 1C, Table S3) validated ELISA results. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) affinities were measured for monovalent VHHs. Monovalent affinities could not be measured for VHH-Fc constructs due to avidity, so the data do not fit the 1:1 model. The sensograms do, however, indicate that multivalent constructs had enhanced binding. Candidates were further evaluated for binding to different domains of the spike protein (RBD, NTD, S2) using ELISA (summarized in Fig. 1D). Using this approach, we were able to identify SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 double cross-reactive clones targeting all 3 domains of the spike protein. In contrast, triple cross-reactive clones that bound to all three spike proteins (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, MERS) were restricted to the S2 domain.

Identification of cross-reactive VHHs following llama immunization. (A) Llama immunization scheme using purified spike proteins from different viruses. (B) ELISA binding results of VHHs showing cross-binding to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins (left panel, monovalent; right panel, bivalent). (C) SPR sensograms of select VHH binders to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Colored curves are raw data at different concentrations of VHH; black curves are fits to a 1:1 model. (D) Table of cross-reactive VHHs targeting different domains (RBD, NTD, S2) within the spike protein. The structure of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein is shown (PDBID: 6XKL) and colored by domain; N-Terminal Domain (NTD) in cyan, Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) in pink, the S2 domain in green, and the stretch between the end of the RBD and beginning of the S2 domain colored gray.

Potent cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2

We initially evaluated neutralization potency of candidate VHHs in the bivalent format using Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-based pseudovirus neutralization assays and observed cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 with several candidates (Fig. 2A, Table S4). In particular, 8 of the candidates, including 10B8 and 1E4, showed potent neutralization for both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Neutralization was observed with all RBD-binding and some NTD-binding antibodies. None of the S2-binding antibodies showed neutralization in SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, or MERS pseudovirus assays (Table S4). Importantly, potent neutralization capability remained for the SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha, Beta and Delta. While potency was reduced against the Omicron variant for some candidates, it remained high for several candidates—particularly 10B8 (Table S4).

Pseudovirus and authentic virus neutralization. (A) SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 VSV pseudovirus neutralization (estimated IC50 values) by 16 candidate VHH-Fcs (bivalent). (B) Authentic SARS-CoV virus neutralization by select candidates (monomeric and bivalent formats). (C) Authentic SARS-CoV-2 virus neutralization by select candidates (monomeric and bivalent formats).

Next, neutralization potency of select candidates were evaluated in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 authentic virus assays. Overall neutralization potency remained similar to what was observed in pseudovirus assays with two of the potent candidates 10B8 and 1E4 showing IC50 values at sub-nM levels for both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2B and C). The bivalent format of 10B8 showed IC50 values of 40 pM and 300 pM for SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, respectively. Even in the monovalent format, IC50 values of 10B8 remained potent (150 pM for SARS-CoV and 2.9 nM for SARS-CoV-2). While the bivalent format of 1E4 remained potent (IC50 values of 50 pM and 200 pM for SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 respectively), the monovalent format of this construct was less potent and IC50 values could not be calculated with the concentrations used in the experiment. Consistent with the literature14, REGN10987 Ab, used as a comparator, showed potent neutralization for SARS-CoV-2 but not for SARS-CoV.

Epitope map** and structural analysis

We used an Octet-based binning assay to evaluate the epitopes of candidate VHHs. Briefly, the first VHH was incubated with the CoV-2 spike protein, which was captured on the biosensor tip, followed by binding of a second antibody. Benchmark antibodies against the RBD (Class 1: REGN1093314, Class 3: REGN1098714, and Class 4: VHH-7215) were included to classify the RBD-targeting VHHs we discovered11. Strikingly, fourteen out of 15 RBD binders binned with VHH-7215 known to bind a cryptic cross-reactive Class 4 epitope on the RBD (Fig. S1A)11. In contrast, one RBD binder (7A9) did not bin with any of the other candidates or benchmark antibodies tested, indicating a novel epitope. We did not find any cross-reactive RBD-targeting VHHs that bound to either the Class 1 or Class 2 epitopes, consistent with literature that epitopes on the top of the RBD are more variable and strain-specific. Likewise, both NTD binding VHHs (19B8 and 16H7) binned together (Fig. S1B). Regarding S2 binders, three of the VHHs that did not bind to MERS binned together, while one triple cross-reactive VHH (6A1) binned separately from the four double cross-reactive VHHs, indicating that they indeed target distinct epitopes on the S2 domain (Fig. S1B). The other two triple cross-reactive VHHs (S3_29, S3_44) were not evaluated in this assay since they bound well to cell surface expressed spike, but poorly to recombinant proteins (Tables S1–S3).

Unlike the well documented cross-reactive antibodies targeting the RBD, benchmark S2-binding antibodies with known epitopes are scarce. Therefore, we utilized hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) to map the epitopes of the three classes of S2 binders we identified. These included 6A1 (triple cross-reactive), 11F5 (double cross-reactive), and S3_29 which was triple cross-reactive in the FACS binding assay (Fig. 3, Fig. S2). Our HDX data revealed three distinct binding epitopes for these S2-targeting VHHs with high confidence. The first epitope (shown in blue in Fig. 3B) is located at the top of the S2 domain and targeted by the triple cross-reactive VHH S3_29. This epitope is similar to that of the recently reported MERS cross-reactive antibody 3A3 and includes the S-2P stabilizing mutations that stabilize our spike construct16. Given the inability of S3_29 to neutralize wild-type virus and its poor binding to recombinant protein, it is likely that these residues are important for stabilizing the conformational epitope at this dynamic region of the protein rather than being directly important for recognition. The second S2 epitope is located at the stem-helix region at the base of the spike protein and targeted by the triple cross-reactive VHH 6A1. The final epitope is also located at the base of the spike protein but above the stem helix region (shown in orange and red), targeted by the double cross-reactive VHH 11F5 and likely by a few other VHHs that bin together with it (Fig. S1B).

Identification of VHH binding epitopes to guide linker length design. The epitopes of select S2 binders were determined by HDX-MS using the spike protein S2 domain. (A) Hydrogen–deuterium exchange difference plots are shown for S3_29, 11F5 and 6A1. Sequence regions showing significant differences are AA962-1006, LVKQLSSNFGAISSVLNDILSRLDKVEAEVQIDRLITGRLQSLQT for S3_29; AA899-916, MQMAYRFNGIGVTQNVL and AA1111-1145, EPQIITTDNFVSGNCDVVIGIVNNTVYDPLQPEL for 11F5; AA1176-1178, VVN and AA1183-1197, DRLNEVAKNLNESL for 6A1. (B) The structure of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein is shown (PDBID: 6XKL) colored gray. The map** for S3_29 is shown in blue. The map** for 11F5 in shown in orange and red marking the sequences protected and deprotected by the VHH respectively. As the region that 6A1 targets has not been resolved in a full spike ectodomain protein structure, it is not shown in this figure.

VHH 7A9 binds a rare RBD epitope and destabilizes the spike trimer

We were intrigued that the RBD-binding VHH 7A9 bound to a cross-reactive epitope that did not bin with any of the benchmark antibodies used in this study. To characterize the 7A9 epitope, we again used HDX-MS, which indicated that the major binding site of 7A9 is partially occluded by the NTD and spans residues 353–364 of the spike protein (Fig. S3). To further analyze this rare antigenic site, we used X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of 7A9 bound to the CoV-2 RBD (Fig. 4, Table S5). The structure reveals that the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) of 7A9 forms a platform through which the VHH binds to a concave cleft on the RBD, inserting Leu107 into a small cleft formed by Tyr396 and Phe464. CDR1 and CDR2 contribute only minimally to the interaction, with Arg31 of CDR1 forming a network of Van der Waals interactions and Tyr60 of CDR2 forming a hydrogen bond with Glu465. The energetic driver of the interaction is likely the salt bridges formed between Arg357 of the RBD and two 7A9 glutamates in CDR3, Glu104 and Glu119. A detailed view of the molecular interactions is shown in Fig. 4B. The structure helps to rationalize how 7A9 is still able to bind and neutralize the Omicron variant (Tables S1, S4), as the epitope does not overlap with any of the 15 RBD mutations in this VOC (Fig. 4C). Notably, the 7A9 epitope is fully occluded in the closed state and partially occluded in the open state of the spike protein (Fig. 4D). Modeling 7A9 binding onto the full CoV-2 spike protein indicates that the VHH would introduce a clash with the NTD from the neighboring spike protomer in either the closed- or open state (Fig. S4). This suggests that either a conformational shift in the RBD relative to the NTD or trimer dissociation would have to occur upon VHH binding. Indeed, recent HDX studies and advances in analysis of heterogeneity in cryo-EM data have shown that the spike protein is quite dynamic and samples states that would potentially expose the 7A9 epitope17,18.

VHH 7A9 binds a rare RBD epitope and triggers spike trimer dissociation. (A) Crystal structure of VHH 7A9 bound to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD. The RBD is shown in light grey with the epitope highlighted in teal. The VHH is shown in dark grey with CDR1, CDR2, and CDR3 highlighted in green, blue, and red, respectively. (B) Molecular interactions between VHH 7A9 and the SARS-CoV-2 RBD. The RBD is shown in light grey with the epitope residues shown in teal. 7A9 is shown in dark grey. Polar interactions are denoted by violet dashed lines. (C) SARS-CoV-2 RBD in cartoon and transparent surface notation with the Cα carbons of residues mutated in the Omicron variant shown as red spheres. The epitope of VHH 7A9 is shown in teal. (D) Overlay of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD from the crystal structure onto the closed (left) or open (right) spike protein structures (PDBs: 7DF3 and 6XKL, respectively). (E) Continuous distribution (c(s)) analyses of analytical ultracentrifugation data. From top to bottom: 7A9 VHH alone, 1E4 VHH alone, SARS-CoV-2 Spike alone, SARS-CoV-2 Spike + 7A9 VHH, and SARS-CoV-2 Spike + 1E4 VHH.

To understand the structural consequences of 7A9 binding to the SARS-CoV-2 spike trimer, we conducted a series of analytical ultracentrifugation sedimentation velocity (AUC-SV) experiments, using a continuous distribution (c(s)) analysis to determine the species present in solution (Fig. 4E, Fig. S5A). The c(s) distribution of the spike alone showed as a single peak (95% of total signal) at 15.9 s, corresponding to an apparent mass of 441 kDa, consistent with a stable trimer (estimated mass of 398 kDa). 7A9 VHH showed as a single peak (93% of total signal) at 2.1 s, corresponding to an apparent mass of 18 kDa, as expected. 7A9 was then mixed with the spike trimer at a 1.5:1 (monomer:monomer) molar ratio. Compared to the spike trimer alone, this mixture displayed a dramatic shift in the sedimentation profile that is readily apparent from the absorbance scans (Fig. S5A). The c(s) distribution revealed 2 major species at 2.2 s (7%) and 8.0 s (86%), with apparent masses of 22 and 155 kDa, respectively. We interpret these species as excess free 7A9 VHH and 7A9 bound to a spike monomer (theoretical mass of 151 kDa). Strikingly, there was no appreciable intact spike trimer (15.9 s) remaining after mixing with 7A9, indicating that binding of 7A9 completely dissociated the spike trimer. To determine if spike trimer dissociation was specifically due to 7A9 binding, we ran identical AUC-SV experiments using the 1E4 VHH, which is predicted to bind to, but not disrupt, the spike trimer. Similar to 7A9 alone, the c(s) distribution of 1E4 alone showed a single peak (98% of total signal) at 2.1 s, corresponding to an apparent mass of 19 kDa. Mixing 1E4 with the spike trimer at a 1.5:1 (monomer:monomer) ratio showed 2 major species at 2.0 s (8%) and 16.7 s (88%), with apparent masses of 20 and 467 kDa, respectively. We interpret these species as excess free 1E4 VHH and 1E4 bound to the spike timer (theoretical mass of 451 kDa). Further, we analyzed identical samples using size-exclusion chromatography coupled to multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) and performed molecular weight calculations via a conjugate analysis method (Fig. S5B). Consistent with the AUC-SV experiments, we observed dissociation of the spike trimer upon binding to 7A9, but not 1E4, with calculated masses of the complexes being comparable to AUC-SV experiments (Fig. S5C). Together, these data clearly indicate that the binding of 7A9 to its cryptic epitope results in the complete dissociation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike trimer, whereas the spike trimer remains intact upon 1E4 binding.

Multimeric design enhances neutralization

It has been reported that multimerization of VHHs can lead to improvement in potency8,19,5, Table S6). A homotrimer of 1E4 showed about a 26-fold improvement in neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus and about 46-fold improvement in neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 authentic virus (Fig. 5A–C). Likewise, a heterotrimeric construct targeting RBD, NTD and S2 showed a 43-fold improvement in neutralization over a cocktail of the same three VHHs in SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus assay (Fig. 5D,E). Importantly, this potency improvement was also observed in authentic SARS-CoV-2 neutralization (Fig. 5F). Additionally, we observed multimerization leading to improved potency with several designs where weakly-neutralizing or non-neutralizing VHHs could be combined to enhance potency (Table S6).

Multimerization of VHH results in enhanced neutralization potency. (A) Design of homotrimeric VHH multimer with 20 aa linker (4 × GGGGS) in between monomeric VHH 1E4. The structure of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein (PDBID: 6XKL) is colored by domain as in Fig. 1. (B) SARS-CoV-2 VSV pseudovirus neutralization by 1E4 VHH monomer vs 1E4 VHH trimer. (C) SARS-CoV-2 authentic virus neutralization by 1E4 VHH monomer vs 1E4 VHH trimer. (D) Design of heterotrimeric VHH multimer with 20 aa linker (4 × GGGGS) in between VHH 7A9 and VHH 19B8 and 50 aa linker (GAS) in between VHH 19B8 and VHH S3_29. The structure of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein (PDBID: 6XKL) is colored by domain as in Fig. 1. Heterotrimeric design with 20 aa linker (4 × GGGGS) in between VHH 7A9 and VHH 19B8 and 50 aa linker (GAS) in between VHH 19B8 and VHH S3_29. (E) SARS-CoV-2 VSV pseudovirus neutralization by 7A9-19B8-S3_29 multimer vs combination of 7A9, 19B8 and S3_29 in equimolar concentrations. (F) SARS-CoV-2 authentic virus neutralization by 7A9-19B8-S3_29 multimer vs combination of 7A9, 19B8 and S3_29 in equimolar concentrations.

Discussion

In this study, we discovered a variety of cross-reactive VHHs against the coronavirus spike protein and characterized the binding affinity, neutralization potency and the epitopes these VHHs target. While the affinities of these VHHs in their monomeric format ranged from < 1 nM to > 100 nM, affinities < 1 nM were observed for the bivalent VHH-Fc format. We found that some of the VHHs have exceptional binding affinity and neutralization potency against SARS-CoV-2 that are comparable to the benchmark antibodies being used in the clinic or in clinical development (Fig. 2C). In addition, these potent antibodies can also neutralize the related coronavirus SARS-CoV and retain activity against the newly emerged Omicron VOC.

The cross-reactive VHHs we identified bind distinct epitopes on the spike protein. The majority of the antibodies cross-react to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, but not to MERS, which was expected as SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are more related and both belong to the Sarbecovirus subfamily. Most of the VHHs we identified target the RBD domain, and all of the RBD-targeting VHHs are neutralizing. This finding is consistent with literature where at least two distinct cross-neutralizing epitopes have been identified on the RBD (Classes 3 and 4)11. Interestingly, most of the RBD VHH antibodies we found target the cryptic Class 4 epitope (targeted by VHH-7215 and CR302213), suggesting that the smaller size of VHH might indeed facilitate interaction with this less accessible antigenic site.

Among the cross-reactive RBD targeting VHHs we discovered, 7A9 is unique, as it is the only VHH identified in this study that is both cross-reactive and does not clearly bin with any other of the Class 1–4 epitopes. Our combined structural approaches clearly demonstrate that 7A9 binds to a highly conserved and cryptic epitope on the RBD that is partially occluded by the CoV-2 spike NTD, providing a structural basis for the retained binding and neutralization of 7A9 to the Omicron variant. Importantly, our data also demonstrates that 7A9 binding leads to the dissociation of the CoV-2 spike trimer. Recently, there have been two reported structures of antibodies that bind to a similar cryptic RBD epitope: the bn03 bispecific VHH (n3130v segment) and 553–49 IgG21,22. Similar to 7A9, both of these antibodies bind to sites that are partially occluded by the NTD of a neighboring protomer in the CoV-2 spike trimer and induce dissociation of the trimer upon binding. However, comparison of the structures of 7A9, bn03, and 553–49 show unique modes of binding for each (Fig. S6A). Comparison of the footprints of each antibody show that the epitopes of 553–49 and bn03 share very little overlap with one-another. The binding site of 7A9 is located in between that of 553–49 and bn03 and shares epitope residues with each of these antibodies (Fig. S6B and C). The divergent mechanisms of these three antibodies are further highlighted by the fact that only RBD residues R355 and R357 are located near the interfaces of all three (Fig. S6C and D). Therefore, each of these antibodies can achieve broad specificity and induce trimer dissociation via distinct mechanisms of binding. It is unclear why these agents exhibit differing levels of viral neutralization, which could be the result of multiple factors including size, binding geometry and valency. Interestingly, several antibodies have been reported in recent years that dissociate other trimeric viral fusion proteins including influenza hemagglutinin and respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein, suggesting that this might a common mechanism of antibody neutralization against respiratory viruses23,24.

A few of the VHHs that were cross-reactive to both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 target NTD and S2, and while some of the NTD binders are neutralizing, none of the S2 binders neutralize. We also found three highly cross-reactive VHHs that also bound to spike protein from MERS, which belongs to a separate subfamily from CoV and CoV-2. All these three VHHs target the S2 domain but did not neutralize any of the three viruses. These data suggest that S2 domain is more conserved and presents multiple distinct cross-reactive epitopes. While these cross-binding S2 antibodies are non-neutralizing, it is possible that they can confer in vivo protection through other Fc-mediated mechanisms. We therefore performed additional characterization to understand the specific epitopes they target. From our HDX map** data, we observed three distinct binding epitopes for S2-targeting VHHs with high confidence. The first epitope is represented by S3_29, which share sequence similarity with one other VHH, and targets the top of the S2 domain. In the closed state of the Spike protein, this region is not exposed or accessible to VHHs. This region could be exposed for VHH binding in one of two ways: (a) when multiple RBDs are in the open state, or (b) following shedding of S1 but prior to the conformational change that precedes membrane fusion. Intriguingly, there is a previous report of an antibody that targets the same region that was mapped similarly using HDX, providing further evidence that this site is accessible25. The second epitope is represented by 6A1 which targets the stem helix region at the base of the spike protein. While not resolved in most spike protein structures, previous studies have reported similar antibodies26,27,28,29. This region is exposed regardless of the conformational state of the prefusion Spike protein. Our binding data suggest that this epitope is the broadest from this study, with reactivity not only to Sarbecovirus and MERS, but also to endemic human coronaviruses HKU1 and OC43 which belong to a different beta coronavirus subfamily from CoV/CoV-2 and MERS. Our data suggests that this region of the spike protein is likely the most conserved. In the future, it would be interesting to evaluate whether antibody binding to this epitope can offer protection against coronavirus infection and disease. The final S2 epitope is represented by 11F5, which binds to the base of the spike protein. Interestingly, this antibody appears to cause both protection and deprotection effects upon binding to the bottom of the spike in our HDX experiment, suggesting that spike undergoes a local conformational change when this antibody binds.

Most of our VHH multimer designs led to potency enhancement, while two designs showed modest loss of potency over their respective VHH cocktails. Significant enhancement in potency was observed with several of our multimer designs. One of the homotrimeric designs, 1E4, showed significant potency enhancement over its monomeric version. However, homotrimers of 10B8 and 7A9 showed no potency enhancement over their respective monomers. One potential reason for this could be due to lack of simultaneous binding to all three protomers with the current design. While homotrimeric VHH constructs targeting RBD epitopes have been shown to enhance potency compared to their monomeric counterparts8,19,44. Solvent A was 0.3% formic acid in water. The injection valve and enzyme column and their related connecting tubings were inside a cooling box maintained at 8 °C. The second switching valve, C8 column and their related connecting stainless steel tubings were inside another chilled circulating box maintained at − 6 °C. Peptide identification was done through searching MS/MS data against the CoV-2 RBD sequence using Byonics (Protein Metrics, CA, USA). The mass tolerance for the precursor and product ions were 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively. The mass spectra for deuterated samples were recorded in MS only mode. Raw MS data was processed using HDX WorkBench, software for the analysis of H/D exchange MS data45. The deuterium levels were calculated using the average mass difference between the deuterated peptide and its undeuterated form (t0).

Crystallization, data collection, and structure determination

The RBD-7A9 complex at 9.5 mg/mL was treated overnight with EndoH at 4 °C and used in crystallization trials without further purification. Crystals of the space group P3221 were grown at 20 ºC by sitting drop vapor diffusion using a drop ratio of 2:1 protein:reservoir solution. Reservoir solution contained 0.2 M sodium malonate pH 6.0 and 18% PEG 3350. Crystals were cryoprotected in reservoir solution supplemented with 25% glycerol.

X-Ray diffraction data were collected at beamline 17-ID at the Advanced Photon Source. Data were processed using autoPROC46 and elliptically truncated using STARANISO47. The structure was solved by molecular replacement in Phenix48 using the SARS-CoV-2 RBD (PDB 7E7Y; Ref.49) and a homology model of 7A9 with the CDRs removed as search models. There was one copy of the complex in the asymmetric unit. The structure was then rebuilt in Coot50 and subjected to iterative rounds of refinement and rebuilding using Phenix and Coot. Data processing and refinement statistics are summarized in Supplementary Table 5.

Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC)

For AUC experiments, we used the SARS-CoV-2-PreS-Closed Spike protein ectodomain, as described above. This construct contains four stabilizing amino acid substitutions (D614N, A892P, A942P, and V987P), and forms a stable trimer without an artificial trimerization sequence. Samples contained 6 μM 7A9 or 1E4 VHH and/or 1.33 μM CoV-2-PreS-Closed Spike trimer (4 μM monomer) in AUC buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5 + 150 mM NaCl). Samples were mixed and then incubated on a rotating platform at room temperature for 3 h. 0.4 mL of each sample was loaded into the right side and 0.4 mL of AUC buffer was loaded into the left side of an AUC cell containing sapphire windows and a double sector charcoal EPON centerpiece. Balanced cells were loaded into an An50Ti rotor and thermally equilibrated in the chamber of a Beckman Optima AUC under vacuum at 25 °C for 1 h. Samples were centrifuged at 40,000 RPM with a total of 300 scans taken at 40 s intervals using absorption optics set at 280 nm. Values for buffer density, viscosity, and partial specific volumes of the proteins were calculated in Sednterp software51. Every 5th scan (60 total) was loaded into the program Sedfit for continuous distribution (c(s)) analysis52. Initial fitting of parameters was iteratively performed to minimize r.m.s.d. values. After testing multiple values, the frictional coefficient was held constant at 1.2 for all samples. After optimizing fit parameters using 60 scans, all 300 scans were analyzed and peaks were integrated in Sedfit. All AUC figures were generated using Matplotlib software53.

Size exclusion chromatography/multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS)

SEC-MALS experiments were performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity II HPLC system using a Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva) at room temperature. The system was equipped with an Agilent HPLC UV‐detector (280 nm) and Wyatt Technology DAWN Heleos II light‐scattering and T‐rEX refractive index detectors. The mobile phase was composed of PBS buffer supplemented with 0.02% sodium azide and was flowed at a rate of 0.5 mL/min. Protein extinction coefficients were calculated based on sequence using Expasy ProtParam assuming 1-to-1 binding for the Spike-VHH complexes. Refractive index values (dn/dc) were estimated at 0.185 and 0.134 mL/g for protein and glycan moieties, respectively. Samples were mixed and incubated as described in the AUC methods section, and subsequently filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane (Millipore). For each run, 0.1 mL of sample (between 11 and 64 μg total protein) was injected onto the column. Molecular weight values were determined in ASTRA software (Wyatt Technology) using a conjugate analysis. The data was exported, and figures were made using GraphPad Prism software.

Multimer design

Following domain binning and HDX epitope map**, the approximate epitope and binding location of many monomeric VHHs against the spike protein were determined. To calculate the length of the desired linker between two VHHs, the distance between the center of the known epitope was measured in both the open and closed state of the spike protein in MOE 2020.09 (Chemical Computing Group). To account for cases where the shortest distance between two sites would result in a clash and to account for the unknown binding orientation of the VHH in relation to the spike protein (where the terminus would be located), an additional buffer distance was added to the initial measurement. Given that an amino acid can cover 3.5–4.0 angstroms in an extended conformation, the measured distance was then converted to a minimum number of amino acids that would be required to bridge such a distance. The resulting number of amino acids was then further converted to the minimum number of linker subunits that could connect the two sites.

Data availability

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structure have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank under accession code 8SK5.

References

Wang, H. et al. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020–21. Lancet 399(10334), 1513–1536 (2022).

Forni, D. et al. Molecular evolution of human coronavirus genomes. Trends Microbiol. 25(1), 35–48 (2017).

Cao, Y. et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature 602(7898), 657–663 (2022).

Dejnirattisai, W. et al. Reduced neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2 omicron B.1.1.529 variant by post-immunisation serum. Lancet 399(10321), 234–236 (2022).

Cele, S. et al. Omicron extensively but incompletely escapes Pfizer BNT162b2 neutralization. Nature 602(7898), 654–656 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 602(7898), 676–681 (2022).

Simpson, S. et al. Disease X: Accelerating the development of medical countermeasures for the next pandemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20(5), e108–e115 (2020).

Schoof, M. et al. An ultrapotent synthetic nanobody neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 by stabilizing inactive Spike. Science 370(6523), 1473–1479 (2020).

Esparza, T. J. et al. High affinity nanobodies block SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain interaction with human angiotensin converting enzyme. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 22370 (2020).

Koenig, P. A. et al. Structure-guided multivalent nanobodies block SARS-CoV-2 infection and suppress mutational escape. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe6230 (2021).

Barnes, C. O. et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody structures inform therapeutic strategies. Nature 588(7839), 682–687 (2020).

Pinto, D. et al. Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Nature 583(7815), 290–295 (2020).

Yuan, M. et al. A highly conserved cryptic epitope in the receptor binding domains of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Science 368(6491), 630–633 (2020).

Baum, A. et al. REGN-COV2 antibodies prevent and treat SARS-CoV-2 infection in rhesus macaques and hamsters. Science 370(6520), 1110–1115 (2020).

Wrapp, D. et al. Structural basis for potent neutralization of betacoronaviruses by single-domain camelid antibodies. Cell 181(5), 1004-1015 e15 (2020).

Silva, R. P. et al. Identification of a conserved S2 epitope present on spike proteins from all highly pathogenic coronaviruses. Elife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.83710 (2023).

Costello, S. M. et al. The SARS-CoV-2 spike reversibly samples an open-trimer conformation exposing novel epitopes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 29(3), 229–238 (2022).

Punjani, A. & Fleet, D. J. 3DFlex: Determining structure and motion of flexible proteins from cryo-EM. Nat. Methods 20(6), 860–870 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Nanobodies from camelid mice and llamas neutralize SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nature 595(7866), 278–282 (2021).

**ang, Y. et al. Versatile and multivalent nanobodies efficiently neutralize SARS-CoV-2. Science 370(6523), 1479–1484 (2020).

Li, C. et al. Broad neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 variants by an inhalable bispecific single-domain antibody. Cell 185(8), 1389-1401 e18 (2022).

Zhan, W. et al. Structural Study of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies identifies a broad-spectrum antibody that neutralizes the omicron variant by disassembling the spike trimer. J. Virol. 96(16), e0048022 (2022).

Harshbarger, W. et al. Convergent structural features of respiratory syncytial virus neutralizing antibodies and plasticity of the site V epitope on prefusion F. PLoS Pathog. 16(11), e1008943 (2020).

Bangaru, S. et al. A Site of vulnerability on the influenza virus hemagglutinin head domain trimer interface. Cell 177(5), 1136-1152 e18 (2019).

Huang, Y., et al., Identification of a conserved neutralizing epitope present on spike proteins from all highly pathogenic coronaviruses. 2021.

Wang, C. et al. A conserved immunogenic and vulnerable site on the coronavirus spike protein delineated by cross-reactive monoclonal antibodies. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 1715 (2021).

Sauer, M. M. et al. Structural basis for broad coronavirus neutralization. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 28(6), 478–486 (2021).

Li, W. et al. Structural basis and mode of action for two broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 emerging variants of concern. Cell Rep. 38(2), 110210 (2022).

Pinto, D. et al. Broad betacoronavirus neutralization by a stem helix-specific human antibody. Science 373(6559), 1109–1116 (2021).

Kirchdoerfer, R. N. et al. Stabilized coronavirus spikes are resistant to conformational changes induced by receptor recognition or proteolysis. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 15701 (2018).

Pallesen, J. et al. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114(35), E7348–E7357 (2017).

Wrapp, D. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367(6483), 1260–1263 (2020).

Juraszek, J. et al. Stabilizing the closed SARS-CoV-2 spike trimer. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 244 (2021).

**ao, X. et al. Profiling of hMPV F-specific antibodies isolated from human memory B cells. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 2546 (2022).

Waldo, G. S. et al. Rapid protein-folding assay using green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 17(7), 691–695 (1999).

Binder, U. & Skerra, A. PASylation®: A versatile technology to extend drug delivery. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 31, 10–17 (2017).

Council, N. R. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 8th edn, 246 (The National Academies Press, 2011).

Association, A.V.M., AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition. 2020. 121.

Percie du Sert, N. et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 18(7), e3000411 (2020).

Pande, K. et al. Hexamerization of Anti-SARS CoV IgG1 antibodies improves neutralization capacity. Front. Immunol. 13, 864775 (2022).

Whitt, M. A. Generation of VSV pseudotypes using recombinant DeltaG-VSV for studies on virus entry, identification of entry inhibitors, and immune responses to vaccines. J. Virol. Methods 169(2), 365–374 (2010).

Schmidt, F. et al. Measuring SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody activity using pseudotyped and chimeric viruses. J. Exp. Med. 217(11), e20201181. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20201181 (2020).

Wu, M. et al. Functionally selective signaling and broad metabolic benefits by novel insulin receptor partial agonists. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 942 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Epitope map** by HDX-MS elucidates the surface coverage of antigens associated with high blocking efficiency of antibodies to birch pollen allergen. Anal. Chem. 90(19), 11315–11323 (2018).

Pascal, B. D. et al. HDX workbench: Software for the analysis of H/D exchange MS data. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 23(9), 1512–1521 (2012).

Vonrhein, C. et al. Data processing and analysis with the autoPROC toolbox. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67(Pt 4), 293–302 (2011).

Tickle, I. J. et al. STARANISO (Global Phasing Ltd., 2018).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66(Pt 2), 213–221 (2010).

Cao, Y. et al. Humoral immune response to circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants elicited by inactivated and RBD-subunit vaccines. Cell Res. 31(7), 732–741 (2021).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60(Pt 12 Pt 1), 2126–2132 (2004).

Hayes, D., Laue, T. & Philo, J. Sedimentation Interpretation Program, Version 1.08 (University of New Hampshire, 2003).

Brown, P. H. & Schuck, P. Macromolecular size-and-shape distributions by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. Biophys. J. 90(12), 4651–4661 (2006).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9(3), 90–95 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Scott Cosmi, formerly of Eurofins Lancaster Laboratories Professional Scientific Service, Lancaster, PA, for his work in purifying the antigen proteins, Eberhard Durr (Infectious Disease and Vaccine Discovery, Merck & Co) for recombinant protein characterization, and Courtney Cohen (United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases/USAMRIID) for assistance with the authentic viral neutralization assays. The authors would also like to thank Capralogics, Inc. for their work in the care and immunization of the llamas used for VHH generation. In addition, the authors would like to thank Kalpit Vora, Jill Chrencik, Mas Handa, and Ilker Donmez for internal review of the manuscript. The authors dedicate this paper in the memory of David Tellers who not only acted as a mentor to a number of authors, but provided thoughtful discussions and key guidance as this work started.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.H., B.H.G., D.M.G., L.Z. and K.P. designed the research. C.L.N., K.V., A.S., M.S., Q.G., H.Z., D.U.G., S.S., Z.W., C.W., X.S.M., D.M., J.G., G.G., M.E., T.M., K.S., F.R., Y.G.-L., A.P., Y.T., S.-J.C., M.B. and C.J. generated reagents and performed the experiments. S.A.H., C.L.N., K.V., C.W., A.F., L.J.K., A.C., L.Z. and K.P. performed analysis. All authors contributed to writing and review of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors except Chengjie Ji are current or former employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. Chengjie Ji is an employee of NovaBioAssays, LLC, Woburn, MA, USA. A subset of the authors (SAH, KV, AS, DUG, BHG, DMG, LZ, and KP) are listed as inventors on a patent surrounding this work held by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hollingsworth, S.A., Noland, C.L., Vroom, K. et al. Discovery and multimerization of cross-reactive single-domain antibodies against SARS-like viruses to enhance potency and address emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Sci Rep 13, 13668 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40919-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40919-7

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Therapeutic nanobodies against SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic human coronaviruses

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2024)