Abstract

Introduction

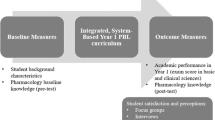

Problem-based learning (PBL) presents unique challenges to longitudinal disciplines such as pharmacology. A curricular supplement (PharmWeb) was created to increase pharmacology knowledge, increase surface learning/recognition memory, and increase deeper learning/production memory.

Methods

First-year medical students (162) were presented 14 brief, optional, self-paced, weekly online learning modules. Usage was assessed by module views and quiz completions. Learning gains were assessed via multiple-choice question (MCQ) pre-/post-tests and existing curriculum assessments (National Board of Medical Examiners [NBME] MCQ customized assessment and an essay examination).

Results

Most students (92 %) visited PharmWeb; users demonstrated significant learning gains (t(32) = 6.12, p < 0.0001; t(19) = 3.34, p < 0.01) from pre-test (means: 50.0, 52.9 %) to post-test (means: 73.1, 65.0 %). Usage predicted increased essay exam performance specifically for pharmacology topics. Pharmacology scores were correlated with total module quizzes completed: r = 0.26, p = 0.001; partialling out the effect of non-pharmacology question scores: r = 0.19, p = 0.014. Students who completed ≥50 % of the PharmWeb quizzes scored significantly higher on pharmacology essay questions (F(1, 161) = 8.1, p = 0.005, Cohen’s d = 0.44), and this difference remained significant after controlling for non-pharmacology scores (ANCOVA: F(1, 160) = 5.0, p = 0.026). Early PharmWeb usage was even more predictive of essay exam performance. Similar results were observed on the NBME customized assessment MCQs, but the effect was not specific to pharmacology.

Conclusions

Students exhibited significant learning gains on both recognition and production memory assessments using voluntary modules encouraging distributed learning. Students’ pharmacology knowledge increased on both recognition and production memory assessments. Thus, supplemental modules may be valuable in supporting deeper learning in longitudinal disciplines within a PBL curriculum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There was a fourth transfer question, but the data for that question was not recorded due to a software error.

References

Patel VL, Yoskowitz NA, Arocha JF. Towards effective evaluation and reform in medical education: a cognitive and learning sciences perspective. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14(5):791–812.

Antepohl W, Herzig S. Problem-based learning versus lecture-based learning in a course of basic pharmacology: a controlled, randomized study. Med Educ. 1999;33(2):106–33.

Dahle LO, Brynhildsen J, Behrbohm Fallsberg M, Rundquist I, Hammar M. Pros and cons of vertical integration between clinical medicine and basic sciences within a problem-based undergraduate medical curriculum: examples and experiences from Linkö**, Sweden. Med Teach. 2002;24(3):280–5.

Neville AJ. Problem-based learning and medical education forty years on. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18(1):1–9.

Faingold CL, Dunaway GA. Teaching pharmacology within a multidisciplinary organ system-based medical curriculum. Naunyn Schmiedebergs’ Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:18–25.

Hughes IE. Computer-based learning—an aid to successful teaching of pharmacology? Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:77–82.

Achike FI. Teaching pharmacology in an innovative medical curriculum: challenges of integration, technology, and future training. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50:6–16.

Franson KL, Dubois EA, de Kam ML, Cohen AF. Measuring learning from the TRC pharmacology e-learning program. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(1):135–41.

Franson KL, Dubois EA, van Gerven JMA, Cohen AF. Development of a visual pharmacology education across an integrated medical school curriculum. J Vis Commune Med. 2007;30(4):156–61.

Lovell K, Plantegenest G. Student utilization of digital versions of classroom lectures. JIAMSE. 2009;19(1):20–5.

Fernandes L, Maley M, Cruickshank C. The impact of online lecture recordings on learning outcomes in pharmacology. JIAMSE. 2008;18(2):62–70.

Marsh KR. Develo** computer-aided instruction within a medical college. JIAMSE. 2008;18(1S):17–28.

Hahne AK, Benndorf R, Frey P, Herzig S. Attitude towards computer-based learning: determinants as revealed by a controlled interventional study. Med Educ. 2005;39:935–43.

Wheeler DW, Whittlestone KD, Salvador R, Wood DF, Johnston AJ, Smith HL, et al. Influence of improved teaching on medical students’ acquisition and retention of drug administration skills. Br J Anesth. 2006;96:48–52.

Degnan BA, Murray LJ, Dunling CP, Whittlestone KD, Standley TDA, Gupta AK, et al. The effect of additional teaching on medical students’ drug administration skills in a simulated emergency scenario. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:1155–60.

Beal T, Kemper KJ, Gardiner P, Woods C. Long-term impact of four different strategies for delivering an on-line curriculum about herbs and other dietary supplements. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:39.

Schmidt H. Integrating the teaching of basic sciences, clinical sciences, and biopsychosocial issues. Acad Med. 1998;73(9):S24–31.

Pinto Pereira LM, Telang BV, Butler KA, Joseph SM. Preliminary evaluation of a new curriculum—incorporation of problem based learning (PBL) into the traditional format. Med Teach. 1993;15(4):351–64.

Kwan CY. Problem-based learning and teaching of medical pharmacology. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366(1):10–7.

Woodman OL, Dodds AE, Frauman AG, Mosepele M. Teaching pharmacology to medical students in an integrated problem-based learning curriculum: an Australian perspective. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25(9):1195–203.

Kwan CY. Learning of medical pharmacology via innovation: a personal experience at McMaster and Asia. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25(9):1186–94.

Karpa KD, Vrana KE. Creating a virtual pharmacology curriculum in a problem-based learning environment: one medical school’s experience. Acad Med. 2013;88:1–8.

Albanese MA, Mitchell S. Problem-based learning: a review of literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Acad Med. 1993;68:52–81.

Donovan JJ, Radosevich DJ. A meta-analytic review of the distribution of practice effect: now you see it, now you don’t. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84:795–805.

Bahrick HP, Hall LK. The importance of retrieval failures to long-term retention: a metacognitive explanation of the spacing effect. J Mem Lang. 2005;52:566–77.

Cepeda NJ, Pashler H, Vul E, Wixted JT, Rohrer D. Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: a review and quantitative analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:354–80.

Magid MS, Schindler MK. Weekly open-book open-access computer-based quizzes for formative assessment in a medical school general pathology course. JIAMSE. 2006;17(1):45–51.

Kerfoot BP, Fu Y, Baker H, Connelly D, Ritchey ML, Genega EM. Online spaced education generates transfer and improves long-term retention of diagnostic skills: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(3):331–7.

Kerfoot BP, Shaffer K, McMahon GT, Baker H, Kirdar J, Kanter S, et al. Online “spaced education progress-testing” of students to confront two upcoming challenges to medical schools. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):300–6.

Kim PY, Allbritton DW, Keri RA, Mieyal JJ, Wilson-Delfosse AL. Creation of an online curriculum to introduce and supplement the learning of pharmacology in a problem-based learning/lecture hybrid curriculum. JIAMSE. 2010;20-2:98–106.

Ornt DB, Aron DC, King NB, Clementz LM, Frank S, Wolpaw T, et al. Population medicine in a curricular revision at Case Western Reserve. Acad Med. 2008;83(4):327–31.

Neville AJ, Normal GR. PBL in the undergraduate MD program at McMaster University: three iterations in three decades. Acad Med. 2007;47:370–4.

Litman L, Davachi L. Distributed learning enhances relational memory consolidation. Learn Mem. 2008;15:711–6.

Xue G, Mei L, Chen C, Lu Z-L, Poldrack R, Dong Q. Spaced learning enhances subsequent recognition memory by reducing neural repetition suppression. J Cogn Neurosci. 2001;23(7):1624–33.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Scholars’ Collaboration in Teaching and Learning participants from 2008–2009 for their feedback on this project, and Irene Medvedev, PhD, Wei Wang, MD, MS, and Siu Yan Scott, LSW, MNO, for their invaluable assistance in project development and data collection. The authors would also like to thank Judy Knight, MLS, AHIP, and Melissa Trace for their tireless assistance with literature searches and obtaining journal articles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, P.Y., Allbritton, D.W., Keri, R.A. et al. Supplemental Online Pharmacology Modules Increase Recognition and Production Memory in a Hybrid Problem-Based Learning (PBL) Curriculum. Med.Sci.Educ. 25, 261–269 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0134-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0134-6