Abstract

Background

Current US hepatitis B mortality rates remain three times higher than the national target. Mortality reduction will depend on addressing hepatitis B disparities influenced by social determinants of health.

Objectives

This study aims to describe characteristics of hepatitis B–listed decedents, which included US birthplace status and county social vulnerability attributes and quantify premature mortality.

Methods

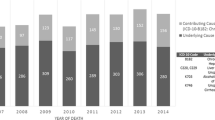

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 17,483 hepatitis B–listed decedents using the 2010–2019 US Multiple-Cause-of-Death data merged with the county-level Social Vulnerability Index (SVI). Outcomes included the distribution of decedents according to US birthplace status and residence in higher versus lower death burden counties by sociodemographic characteristics, years of potential life lost (YPLL), and SVI quartiles.

Results

Most hepatitis B–listed decedents were US-born, male, and born during 1945–1965. Median YPLL was 17.2; 90.0% died prematurely. US-born decedents were more frequently White, non-college graduates, unmarried, and had resided in a county with < 500,000 people; non-US-born decedents were more frequently Asian/Pacific Islander, college graduates, married, and had resided in a county with ≥ 1 million people. Higher death burden (≥ 20) counties were principally located in coastal states. US-born decedents more frequently resided in counties in the highest SVI quartile for “Household Characteristics” and “Uninsured,” whereas non-US-born decedents more frequently resided in counties in the highest SVI quartile for “Racial/Ethnic Minority Status” and “Housing Type/Transportation.”

Conclusion

This analysis found substantial premature hepatitis B mortality and residence in counties ranked high in social vulnerability. Successful interventions should be tailored to disproportionately affected populations and the social vulnerability features of their geographic areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Restricted-use US Multiple Cause of Death data were acquired through an approved project determination to the CDC National Center for Health Statistics to obtain information on state and county of decedent residence and birth. The public-use CDC Social Vulnerability Index data were obtained from the CDC’s Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry website.

Code Availability

Statistical codes used for these analyses are available upon request.

Abbreviations

- ATSDR:

-

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

- CCOD:

-

Contributing cause of death

- CDC:

-

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CHB:

-

Chronic hepatitis B

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COD:

-

Cause of death

- DC:

-

District of Columbia

- DHHS:

-

US Department of Health and Human Services

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HDV:

-

Hepatitis D virus

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MCOD:

-

Multiple Cause of Death

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- SDOH:

-

Social determinants of health

- SVI:

-

Social vulnerability index

- UCOD:

-

Underlying cause of death

- US:

-

United States

- YPLL:

-

Years of potential life lost

References

US Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States: A Roadmap to Elimination (2021–2025). Washington, DC.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis surveillance–United States. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/SurveillanceRpts.htm. Accessed on March 27, 2023.

Ly KN, Yin S, Spradling PR. Regional differences in mortality rates and characteristics of decedents with hepatitis B listed as a cause of death, United States, 2000–2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2219170.

Harris AM, Iqbal K, Schillie S, Britton J, Kainer MA, Tressler S, Vellozzi C. Increases in acute hepatitis B virus infections - Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, 2006–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):47–50.

Conners EE, Panagiotakopoulos L, Hofmeister MG, et al. Screening and testing for hepatitis B virus infection: CDC recommendations — United States, 2023. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2023;72(1):1–25.

Weng MK, Doshani M, Khan MA, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in adults aged 19–59 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2022. MMWR Weekly. 2022;71(13):477–83.

Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67(4):1560–99.

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67(2):370–98.

Gordon SC, Lamerato LE, Rupp LB, et al. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B virus infection and development of hepatocellular carcinoma in a US population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):885–93.

Lok AS, Perrillo R, Lalama CM, et al. Low incidence of adverse outcomes in adults with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the era of antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2021;73(6):2124–40.

Kim HS, Yang JD, El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Awareness of chronic viral hepatitis in the United States: an update from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26(5):596–602.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030: Social determinants of health literature summaries. Available at https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries#block-sdohinfographics. Accessed on June 13, 2023.

CDC Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. CDC/ATSDR Social vulnerability index. Available at https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html. Accessed on January 13, 2023.

Bevan G, Pandey A, Griggs S, Dalton JE, Zidar D, Patel S, et al. Neighborhood-level social vulnerability and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and coronary heart disease. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023;48(8):101182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2022.101182.

Ganatra S, Dani SS, Kumar A, et al. Impact of social vulnerability on comorbid cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality in the United States. JACC CardioOncol. 2022;4(3):326–37.

Knoebel RW, Kim SJ. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic, social vulnerability, and opioid overdoses in Chicago. AJPM Focus. 2023;2(2): 100086.

Zambrano LD, Ly KN, Link-Gelles R, et al. Investigating health disparities associated with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41(11):891–8.

Tipirneni R, Schmidt H, Lantz PM, Karmakar M. Associations of 4 geographic social vulnerability indices with US COVID-19 incidence and mortality. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(11):1584–8.

CDC National Centers for Health Statistics. Restricted-use vital statistics data. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/nvss-restricted-data.htm. Accessed on January 13, 2023.

Organization. WH. International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). World Health Organization; 1992.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US standard certificate of death. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/death11-03final-acc.pdf. Accessed on February 20, 2024.

Arias E. United States life tables, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(7):1–63.

Arias E. United States Life Tables, 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(11):1–63.

Arias E, Heron M, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(8):1–65.

Arias E, Heron M, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66(3):1–64.

Arias E, Heron M, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66(4):1–64.

Arias E, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(7):1–64.

Arias E, Xu J, Kochanek KD. United States Life Tables, 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(4):1–66.

Arias E. United States Life Tables, 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(7):1–66.

Arias E, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2020;69(12):1–45.

Arias E, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2019. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2022;70(19):1–59.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Principles of Epidemiology. Lesson 3: measures of risk. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson3/section3.html. Accessed on July 24, 2023.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER Multiple Cause of Death 1999–2020 Dataset Documentation. Available at https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/mcd.html#. Accessed on June 13, 2023.

Ghany MG, Perrillo R, Li R, et al. Characteristics of adults in the hepatitis B research network in North America reflect their country of origin and hepatitis B virus genotype. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(1):183–92.

Schmid KL, Rivers SE, Latimer AE, Salovey P. Targeting or tailoring? Mark Health Serv. 2008;28(1):32–7.

Weinbaum CM, Mast EE, Ward JW. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S35-44.

Khalili M, Leonard KR, Ghany MG, et al. Racial disparities in treatment initiation and outcomes of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in North America. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e237018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 Viral hepatitis surveillance report. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2020surveillance/index.htm. Accessed on June 16, 2023.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug overdose death rate maps & graphs. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/index.html. Accessed on June 16, 2023.

Bixler D, Zhong Y, Ly KN, et al. Mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis B infection: The Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS). Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(6):956–63.

Ly KN, Speers S, Klevens RM, Barry V, Vogt TM. Measuring chronic liver disease mortality using an expanded cause of death definition and medical records in Connecticut, 2004. Hepatol Res. 2015;45(9):960–8.

Manos MM, Leyden WA, Murphy RC, Terrault NA, Bell BP. Limitations of conventionally derived chronic liver disease mortality rates: results of a comprehensive assessment. Hepatology. 2008;47(4):1150–7.

Arias E, Schauman WS, Eschbach K, Sorlie PD, Backlund E. The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. Vital Health Stat 2. 2008;148:1–23.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public use data file documentation mortality multiple cause-of-death. Avalable at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_public_use_data.htm. Accessed on June 26, 2023.

Shih YT, Bradley C, Yabroff KR. Ecological and individualistic fallacies in health disparities research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;115(5):488–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of state and local health departments who provide death certificate data to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Kathleen Ly, Shaoman Yin, and Philip Spradling. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Kathleen Ly and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. CDC scientific coauthors were involved in the design and conduct of the study; analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Collection and management of the original source US Multiple Cause of Death data were conducted prior to this analysis through an ongoing cooperative agreement between each state health department and the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This analysis did not require institutional review board review per HHS Code of Federal Regulations Title 45 Part 46 2018 because de-identified data were obtained for decedents from secondary sources.

Consent to Participate

This study was deemed exempt from institutional review board review and informed consent per HHS Code of Federal Regulations Title 45 Part 46 2018 because all data were obtained from secondary sources without personally identifiable information.

Consent for Publication

This study was deemed exempt from institutional review board review and informed consent per HHS Code of Federal Regulations Title 45 Part 46 2018 because all data were obtained from secondary sources without personally identifiable information.

CDC Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ly, K.N., Yin, S. & Spradling, P.R. Disparities in Social Vulnerability and Premature Mortality among Decedents with Hepatitis B, United States, 2010–2019. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-01968-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-01968-4