Abstract

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents is becoming a widespread health issue. Recent studies have suggested that repetitive NSSI is crucial in NSSI adolescents and can be conceptualized as an “addictive behavior.” The aim of this cross-sectional study was to explore the network relationships among child maltreatment, anxiety, and addictive NSSI in adolescents. In total, 542 adolescents (14.07 ± 2.15 years old, 18.6% males) with NSSI behavior completed the related questionnaires. Two types of psychometric approaches were used to analyze the data. First, the network analysis showed that emotional abuse (Expected Influence: 1.20) had the most central role among the networks, and the edges of emotional abuse–anxiety (weight: 0.25), emotional abuse-addictive NSSI (weight: 0.20), and anxiety–addictive NSSI (weight: 0.19) showed stronger positive associations of trans-symptom edges. Second, the network comparison test was used to examine the network differences between the male and female groups; however, no network differences were found. Overall, among all types of childhood maltreatment, our results suggest that emotional abuse should be more emphasized to prevent long-term mental adverse outcomes and addictive NSSI, and that anxiety may also mediate emotional abuse and addictive NSSI in NSSI adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is defined as any deliberate, direct, or repetitive physically harmful act to the body, such as cutting, burning, hitting, scratching, or hair pulling, but without a suicide attempt (Esposito et al., 2019; Hawton et al., 2016). Adolescents are a group between childhood and adulthood, from ages 10 to 24 (Sawyer et al., 2018). Individuals experience rapid physical, cognitive, and psychosocial growth during this period, as well as a peak onset of mental disorders (Jia & Schumann, 2022). For example, adolescents are a group with a high incidence of NSSI behavior, especially since the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic (R. T. Liu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2020), and NSSI behavior in adolescents has emerged in large numbers, which has aroused widespread concern.

NSSI behavior includes a series of factors, such as NSSI ideation, NSSI frequency, NSSI motivation, and repetitive NSSI (Nixon et al., 2015). In recent years, repetitive NSSI has been regarded as crucial to NSSI among adolescents and has been conceptualized as an “addictive behavior” (Guérin-Marion et al., 2018). At present, behavioral measurements of NSSI in adolescents have described addictive NSSI as an independent feature of NSSI, and the most widely used measurement tool is the Ottawa Self-Injury Inventory (OSI) (Nixon et al., 2015). The OSI’s addiction characteristics item is derived from the DSM-IV-TR substance dependence criteria (Guérin-Marion et al., 2018). Previous studies have pointed out that the addictive characteristics of NSSI are similar to those of substance use disorder, which is typically characterized by a loss of control over the behavior of NSSI, engaging in it despite the negative consequences, and thus develo** a significant tolerance and dependence on the behavior (Buser & Buser, 2013).

Addictive NSSI in adolescents is closely associated with early maltreatment in childhood. Large sample studies of young adults and adolescents suggest that a greater possibility of addictive NSSI may be associated with specific developmental risk contexts, such as perceived paternal abuse and physical abuse in childhood (Martin et al., 2016; Ying et al., 2023). Adequate evidence from meta-analyses has also indicated that childhood maltreatment and its subtypes, especially sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect, are associated with NSSI behavior (Hailes et al., 2019; R. T. Liu et al., 2018). Childhood abuse is associated with an increased risk of long-term mental health outcomes and has adverse effects (Iram Rizvi & Najam, 2014). For example, it can lead to a significantly increased risk of anxiety disorders in adolescence or adulthood (Lereya et al., 2015). Psychological distress or anxiety is considered significant risk factor for repetitive NSSI in adolescents (Plener et al., 2015; Rahman et al., 2021). Moreover, the current theory holds that repetitive NSSI enables adolescents to alleviate negative emotions such as anxiety (Bresin & Gordon, 2013; Glenn & Klonsky, 2013). Thus, there was a strong correlation between childhood maltreatment, anxiety, and addictive NSSI. However, evidence on how childhood maltreatment affects current anxiety and its further related to addictive NSSI in adolescents is lacking.

Network analysis, an emerging data-driven method, assesses the associations between complex variables, identifies the most important variables and how they are related, and displays the results in a visual and intuitive way (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; S. Epskamp & Fried, 2018; Galderisi et al., 2018). There are two basic elements in psychometric network analyses: nodes and edges. Variables (such as mental symptoms) are typically represented as nodes, and an edge represents a partial correlation between two nodes (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; Sacha Epskamp et al., 2012). A network analysis approach can reveal centrality, enabling an understanding of the relative influences various nodes have on the whole network, and central nodes may be potential targets for clinical interventions (Rogers et al., 2019). Hence, network analysis may help to identify the central variables and the differential associations among childhood maltreatment, anxiety, and addictive NSSI among NSSI adolescents.

In the present study, we applied network analysis to collected clinical data on childhood maltreatment, anxiety, and addictive NSSI in a large sample of NSSI adolescents to understand the complex interactions among these domains with each other. Findings from this data-driven approach can better inform addictive NSSI prevention and intervention strategies.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from two clinical centers in eastern China. In the original sample, a total of 566 NSSI adolescents completed the primary survey for possible inclusion in the study. Twenty-four adolescents did not complete all the scales. Therefore, a total of 542 adolescents (14.07 ± 2.15 years old, 18.6% males) with NSSI features were included in the present study. The criteria for diagnoses followed the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition).

Measures

Childhood Maltreatment

The Chinese version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Fu et al., 2005) was used to assess childhood trauma. The questionnaire has 28 questions that are divided into five subscales: emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical abuse, physical neglect, and sexual abuse. The questionnaire used a five-point Likert scale, from 1 to 5 representing never to always, respectively, with higher scores on each subscale indicating more serious abuse.

Anxiety

The Chinese version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Zheng et al., 2022) was used to assess the severity of general anxiety symptoms. The inventory included 21 self-reported items. Participants scored each item from 0 to 3 based on the intensity of the physical and cognitive anxiety symptoms experienced during the previous 2 weeks, with higher scores indicating greater symptom intensity. Scores for each of the 21 items were added together, and a higher total score represented more severe anxiety.

NSSI Addiction

The Chinese version of the Ottawa Self-Injury Inventory (OSI) (Hui et al., 2022) was used to assess addictive features in the NSSI group. Addictive features of NSSI were evaluated via seven items that were derived from DSM-IV-TR criteria on substance dependence, each scored on a scale of 0 (never) to 4 (always). Individual item scores were summed, and a high total score indicated that an individual’s NSSI behavior was more addictive.

The present study adopted the Chinese versions of the CTQ, the SAS, and the OSI, which have been found to have satisfactory reliability and clinical validity.

Statistical Analysis

The network analyses were conducted using the R package qgraph (Sacha Epskamp et al., 2012; S. Epskamp & Fried, 2018). Nodes represent the items that were entered into the network analysis. The lines between nodes are called edges, which are partially correlated after taking into account all other correlations. The size of the correlation value is shown by the thickness of the line, with a thicker edge representing a stronger correlation. Different edge colors represent positive (blue) and negative (red) correlations. Polychoric correlations were used to calculate the correlation between nodes, and the Gaussian graphical model was used to estimate the network (Wainwright & Jordan, 2008). The Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm was used to determine the position of the nodes in the network graph (Fruchterman & Reingold, 1991). The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) (Costantini et al., 2015; Friedman et al., 2008) and the extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC) (Chen & Chen, 2008; Foygel & Drton, 2010) were applied to handle possible false-positive edges in the network analysis. LASSO shrinks all edges and sets small edges to exactly zero to obtain a more stable and sparse network that is easier to interpret (Friedman et al., 2008). The EBIC estimated 100 network models with different sparsities and selected the model with the lowest EBIC (Sacha Epskamp et al., 2016). The construction of the network used Spearman’s correlations.

We estimated the centrality of the nodes by calculating the expected influence (EI) value. Compared with traditional centrality indicators (such as strength or closeness), EI values are considered more appropriate for network evaluation because they simultaneously consider positive and negative edges (Bringmann et al., 2019; Robinaugh et al., 2016). The EI value is a measure of the connection of an item to other items in the entire network, which is the sum of all the edges (Guo et al., 2022). The larger the EI value of an item is, the greater the importance of this node and the greater its activation in the network (Robinaugh et al., 2016).

We used the bootstrap** method in the R package bootnet to examine the accuracy of the edge-weight by assessing 95% confidence intervals (Sacha Epskamp et al., 2016; S. Epskamp & Fried, 2018). Furthermore, the centrality stability coefficient (CS coefficient) was used as a reference index to assess the stability of the EI. A value higher than 0.25 was acceptable, and a value higher than 0.5 was preferred (S. Epskamp & Fried, 2018).

The NetworkComparisonTest (NCT) package was used to test the network differences between males and females. The differences between networks were compared from three subtests: a network structure invariance test, a global strength invariance test, and an edge strength invariance test. The network invariance test was evaluated by the differences in the strength of the maximum edge of the network; the global strength invariance test was evaluated by the differences in the sum of the edge strengths; and the edge invariance test was evaluated by the differences between specific edges in the network (van Borkulo et al., 2023). The differences in individual edges between networks were compared after controlling for multiple comparisons using Holm–Bonferroni corrections.

We also performed a normal distribution test for the variables included in the network analysis and an independent-sample T-test based on gender.

Results

The cross-sectional study included 542 adolescents with NSSI behavior, and their anxiety, five forms of maltreatment, and the addictive NSSI features were measured to estimate the regularized correlational network by network psychometric approaches. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all analysis variables, and all of them were normally distributed. Table 2 presents the gender differences for all variables among 542 participants; only addictive NSSI shows the significant gender difference, and females have higher addictive NSSI feature than males (p = 0.000).

Network Analysis

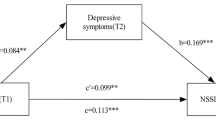

We aimed to estimate the differential interactions between five forms of maltreatment, anxiety, and addictive NSSI through network analysis. Figure 1 presents the results of the network structure. We observed that childhood maltreatment had strong internal connections in this network. Specially, strongly positive connections exhibited in edges between emotional abuse and physical abuse (weight: 0.45) and between emotional neglect and physical neglect (weight: 0.45). Regarding the trans-symptom connections between childhood maltreatment and anxiety and addictive NSSI, we further found that both emotional abuse and physical neglect were positively connected with anxiety; however, bootstrapped difference test of all edges showed emotional abuse (weight: 0.25) connected to anxiety with significant higher weights compared to physical neglect (weight: 0.12). Emotional abuse is also positively associated with addictive NSSI (weight: 0.19). Lastly, a positive connection between anxiety and addictive NSSI (weight: 0.20) was showed in this network.

Regarding the expected influence, Fig. 2 depicts the centrality of all nodes. The standardized centrality estimates show that emotional abuse had the highest EI value (1.20) among all nodes in the network, indicating that this node significantly impacted the entire network. Finally, regarding the stability of node centrality, the correlation stability coefficient for EI was 0.749, indicating excellent stability.

The results of centrality EI stability and edge weight accuracy are shown in Supplementary Figure S1 and S2. The bootstrapped difference tests for node centrality and edge weights are shown in Supplementary Figure S3 and S4.

Network Comparison Test

The networks for male and female NSSI adolescents did not differ significantly through NCT permutation tests of network structure invariance (maximum difference in edge weights = 0.17, p = 0.65) and the global strength invariance (strength difference = 0.25, p = 0.88) and the edge variance (all edges p > 0.05). The networks of the two groups are presented in Fig. 3.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to utilize network psychometrics to investigate the differential associations of childhood maltreatment and anxiety and addictive NSSI in adolescents with NSSI. Specifically, the results suggested that emotional abuse was the only significant centrality among the relations of childhood maltreatment, anxiety, and addictive NSSI. Emotional abuse was found to have positive trans-symptom connections with both anxiety and addictive NSSI, and anxiety was positively associated with addictive NSSI. Additionally, no differences in network structure were found between males and females.

Both childhood maltreatment and anxiety are important risk factors affecting NSSI behavior in adolescents (Wang et al., 2022). However, anxiety is a long-term adverse mental outcome caused by maltreatment during childhood (Lereya et al., 2015). Meta-analysis evidence has suggested that all five forms of childhood maltreatment are risk factors for anxiety disorders (Gardner et al., 2019). The positive connections between childhood maltreatment and anxiety in the present study further support that adverse experiences in early stages may lead to more serious anxiety in NSSI adolescents, especially, the experience of emotional abuse. In the network, emotional abuse had the highest EI value and occupied the most central position among all included items. This result indicates that emotional abuse plays the most crucial and reliable role in the trans-symptom network. Certainly, in related studies, emotional abuse also displayed the mostly central role among various forms of childhood maltreatment and significantly contributes to adverse mental outcomes, such as depression and PTSD in young adults (A. Liu et al., 2023). Furthermore, young adults with higher levels of emotional abuse may also process negative information more easily (Y. Liu et al., 2021).

Previous partial evidence has shown that a specific growth context or adverse childhood experience increases the risk of addictive NSSI (Martin et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022). Regarding the connections of childhood maltreatment with addictive NSSI in the present study, only emotional abuse presented a positive connection with addictive NSSI. Although previous studies have revealed risk factors for NSSI (Wang et al., 2022) and the development of NSSI over time among adolescents (De Luca et al., 2023), this evidence emphasizes general NSSI behavior more than addictive NSSI behavior specifically. We mentioned that repeated NSSI is an addictive behavior, and the addictive nature of NSSI has been salient; however, it is still important to explore how it develops and which risk factors may increase vulnerability to addictive NSSI (Guérin-Marion et al., 2018). A recent study (Ying et al., 2023) indicated that physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and physical neglect were likely associated with addictive NSSI. However, physical abuse was the only significant risk factor for addictive NSSI in outpatient adolescents and young individuals. However, they also noted that these results may not be reliable enough to determine which factor had the most influence because of the correlations between childhood maltreatment and other clinical outcomes. Based on their findings, our results explicitly support that emotional abuse presented direct connections with addictive NSSI when considering the anxiety outcomes in NSSI adolescents.

Psychological distress or anxiety is also considered a significant risk factor for self-harm repetition in adolescents (Plener et al., 2015; Rahman et al., 2021). The mainstream theory suggests that NSSI can alleviate psychological distress associated with trauma-related symptoms in adolescent psychiatric inpatients (Nock & Prinstein, 2005). Thus, from this perspective, we speculated that as adolescents with NSSI experience more negative emotions, they become increasingly anxious, which in turn increase their likelihood of engaging in addictive NSSI behaviors as a means of relief. The directly positive connection between anxiety and addictive NSSI is consistent with these findings.

Based on the discussion above, to sum up, the positively interactions between anxiety, emotional abuse, and addictive NSSI offer new insights into whether anxiety may also potentially regulate the relationship between emotional abuse and addictive NSSI. In other words, we suggest that the adverse mental outcomes caused by childhood maltreatment should be taken into consideration when assessing the relationships between childhood maltreatment and addictive NSSI in adolescents.

Lastly, gender difference is an important variable impacting addictive NSSI. Females were identified as a strong predictor of addictive NSSI as reported in a previous study, and they also suggested that offering more attention to females could help prevent addictive NSSI (Ying et al., 2023). Similarly, according to the gender ratio and scale scores of our participants, our results also demonstrated that females present higher addictive NSSI features than males, which partly indicates that females were more prone to addictive NSSI behavior. The potential reason for the gender difference in addictive NSSI may be linked to the higher prevalence of mood disorders (such as anxiety and depression) in female adolescents (Li et al., 2022). When facing stressors or negative emotions, however, females are more likely to adopt emotion-oriented co** strategies to relieve negative emotions, and addictive NSSI is one of the main choices (Nixon et al., 2015). However, the network comparison test did not reveal any network differences related to gender among childhood maltreatment, anxiety, and addictive NSSI. We speculated that this may be mainly related to the gender sample difference; the limited number of male participates may result in less significant differences in the comparison of network structure.

The current findings must be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, we employed a cross-sectional study design, which may constrain the interpretability of our results. The utilization of a longitudinal design in future studies may confirm and extend our results and allow for assessments of causality. Then, more male samples need to be collected to perform network comparison with females, which may be helpful to understand the network differences of gender. Finally, as we included anxiety outcomes in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and addictive NSSI, other adverse mental outcomes should be analyzed in future studies to obtain more comprehensive network connections, such as cyberbullying (Bansal et al., 2023).

Conclusion

The main strength of this study was the network psychometric approaches, which provided a data-driven pathway to investigate the interplay of childhood maltreatment, anxiety, and addictive NSSI. In conclusion, among all five abuse factors, our findings suggest that emotional abuse is of particular significance; it affects anxiety in adolescents with NSSI more than all other forms of maltreatment, and it may also affect addictive NSSI directly or through the potentially mediating effect of anxiety among adolescents with NSSI. It would be valuable to develop new therapies or research avenues based on the associations among emotional abuse and anxiety and addictive NSSI identified in this study for use in clinical practice.

Data Availability

Due to the particularity of the participants and the need to protect privacy, the original data cannot be publicly obtained, and the code of data processing has been publicly uploaded: https://osf.io/f2ca5/.

References

Bansal, S., Garg, N., Singh, J., & Van Der Walt, F. (2023). Cyberbullying and mental health: Past, present and future. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1279234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1279234

van Borkulo, C. D., van Bork, R., Boschloo, L., Kossakowski, J. J., Tio, P., Schoevers, R. A., . . . Waldorp, L. J. (2023). Comparing network structures on three aspects: a permutation test. Psychologyl Methods, 28(6), 1273–1285. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000476

Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608

Bresin, K., & Gordon, K. H. (2013). Endogenous opioids and nonsuicidal self-injury: A mechanism of affect regulation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(3), 374–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.020

Bringmann, L. F., Elmer, T., Epskamp, S., Krause, R. W., Schoch, D., Wichers, M., . . . Snippe, E. (2019). What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? Journal of Abnorm Psychology, 128(8), 892–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000446

Buser, T. J., & Buser, J. K. (2013). Conceptualizing nonsuicidal self-injury as a process addiction: Review of research and implications for counselor training and practice. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 34, 16–29.

Chen, J., & Chen, Z. (2008). Extended Bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika, 95, 759–771.

Costantini, G., Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., Perugini, M., Mõttus, R., Waldorp, L. J., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2015). State of the aRt personality research: A tutorial on network analysis of personality data in R. Journal of Research in Personality, 54, 13–29.

De Luca, L., Pastore, M., Palladino, B. E., Reime, B., Warth, P., & Menesini, E. (2023). The development of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) during adolescence: A systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 339, 648–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.091

Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617–634. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000167

Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). Qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–18.

Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2016). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50, 195–212.

Esposito, C., Bacchini, D., & Affuso, G. (2019). Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and its relationships with school bullying and peer rejection. Psychiatry Research, 274, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.018

Foygel, R., & Drton, M. (2010). Extended Bayesian information criteria for Gaussian graphical models. Paper presented at the NIPS.

Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2008). Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics, 9(3), 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxm045

Fruchterman, T. M. J., & Reingold, E. M. (1991). Graph drawing by force‐directed placement. Software: Practice Experience, 21.

Fu, W.Q., Y, S., Yu, H.H., Zhao, X.F., Li, R., Li, Y., Zhang, YQ. (2005). Reliability and validity of childhood trauma questionnaire in Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40–42.

Galderisi, S., Rucci, P., Kirkpatrick, B., Mucci, A., Gibertoni, D., Rocca, P., . . . Maj, M. (2018). Interplay among psychopathologic variables, personal resources, context-related factors, and real-life functioning in individuals with Schizophrenia: a network analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4607

Gardner, M. J., Thomas, H. J., & Erskine, H. E. (2019). The association between five forms of child maltreatment and depressive and anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse and Neglect, 96, 104082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104082

Glenn, C. R., & Klonsky, E. D. (2013). Nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: An empirical investigation in adolescent psychiatric patients. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42(4), 496–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.794699

Guérin-Marion, C., Martin, J., Deneault, A. A., Lafontaine, M. F., & Bureau, J. F. (2018). The functions and addictive features of non-suicidal self-injury: A confirmatory factor analysis of the Ottawa self-injury inventory in a university sample. Psychiatry Research, 264, 316–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.019

Guo, Z., He, Y., Yang, T., Ren, L., Qiu, R., Zhu, X., & Wu, S. (2022). The roles of behavioral inhibition/activation systems and impulsivity in problematic smartphone use: A network analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1014548. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1014548

Hailes, H. P., Yu, R., Danese, A., & Fazel, S. (2019). Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: An umbrella review. Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 830–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(19)30286-x

Hawton, K., Witt, K. G., Taylor Salisbury, T. L., Arensman, E., Gunnell, D., Hazell, P., . . . van Heeringen, K. (2016). Psychosocial interventions for self-harm in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016(5), Cd012189. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.Cd012189

Chen, Hui, P. B., ZHANG Chenyun, GUO Yang, ZHOU Jiansong, WANG **. (2022). Revision of the non-suicidal self-injury behavior scale for adolescents with mental disorder. Journal of Central South University(Medical Science), 03(47), 301–308.

Iram Rizvi, S. F., & Najam, N. (2014). Parental psychological abuse toward children and mental health problems in adolescence. Pak J Med Sci, 30(2), 256–260.

Jia, T., & Schumann, G. (2022). How cognitive neuroscience can enhance education and population mental health. Sci Bull (bei**g), 67(15), 1542–1543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2022.07.001

Lereya, S. T., Copeland, W. E., Costello, E. J., & Wolke, D. (2015). Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: Two cohorts in two countries. Lancet Psychiatry, 2(6), 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00165-0

Li, F., Cui, Y., Li, Y., Guo, L., Ke, X., Liu, J., . . . Leckman, J. F. (2022). Prevalence of mental disorders in school children and adolescents in China: diagnostic data from detailed clinical assessments of 17,524 individuals. 63(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13445

Liu, R. T., Scopelliti, K. M., Pittman, S. K., & Zamora, A. S. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(17)30469-8

Liu, Y., Peng, H., Wu, J., & Duan, H. (2021). The relationship between childhood emotional abuse and processing of emotional facial expressions in healthy young men: Event-Related Potential and behavioral evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 686529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686529

Liu, R. T., Walsh, R. F. L., Sheehan, A. E., Cheek, S. M., & Sanzari, C. M. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(7), 718–726. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1256

Liu, A., Liu, M., Ren, Y., Lin, W., & Wu, X. (2023). Exploring gender differences in the relationships among childhood maltreatment, PTSD, and depression in young adults through network analysis. Child Abuse and Neglect, 146, 106503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106503

Martin, J., Bureau, J. F., Yurkowski, K., Fournier, T. R., Lafontaine, M. F., & Cloutier, P. (2016). Family-based risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury: Considering influences of maltreatment, adverse family-life experiences, and parent-child relational risk. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.015

Nixon, M. K., Levesque, C., Preyde, M., Vanderkooy, J., & Cloutier, P. F. (2015). The Ottawa self-injury inventory: Evaluation of an assessment measure of nonsuicidal self-injury in an inpatient sample of adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0056-5

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2005). Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.114.1.140

Plener, P. L., Schumacher, T. S., Munz, L. M., & Groschwitz, R. C. (2015). The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: a systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personality Disorder Emotion Dysregulation, 2.

Rahman, F., Webb, R. T., & Wittkowski, A. (2021). Risk factors for self-harm repetition in adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 88, 102048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102048

Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J., & McNally, R. J. (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000181

Rogers, M. L., Hom, M. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2019). Differentiating acute suicidal affective disturbance (ASAD) from anxiety and depression symptoms: A network analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 250, 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.005

Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

Wainwright, M. J., & Jordan, M. I. (2008). Graphical models, exponential families, and variational inference. Journal of Foundations Trends Machine Learning, 1, 1–305.

Wang, Y. J., Li, X., Ng, C. H., Xu, D. W., Hu, S., & Yuan, T. F. (2022). Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 46, 101350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101350

Ying, W., Shen, Y., Ou, J., Chen, H., Jiang, F., Yang, F., . . . Dong, H. (2023). Identifying clinical risk factors correlated with addictive features of non-suicidal self-injury among a consecutive psychiatric outpatient sample of adolescents and young adults. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-023-01636-4

Zhang, L., Zhang, D., Fang, J., Wan, Y., Tao, F., & Sun, Y. (2020). Assessment of mental health of Chinese primary school students before and after school closing and opening during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2021482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21482

Zheng, JR. H. C., Huang, J.J., Zhaung, X.Q., Wang, D.B., Zheng, S.Y., Huang, X.Y., Chen, Q.Y., Wu, JA. (2022). Study on psychometric characteristics, norm scores and factor structure of Beck Anxiety Inventory. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 4–6.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (grant number 21JZDW007), Ningbo Clinical Medical Research Centre for Mental Health (No.2022L002), Ningbo Top Medical and Health Research Program (No.2022030410), the Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo (2021J272), Ningbo medical and health brand discipline (No.PPXK 2024-07), and the Shanghai Academy of Educational Sciences project A study on students’ care in primary and secondary schools.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG-Z analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; XL-L collected the data and wrote the manuscript; WL-X, WW-Z, and HH-Y collected the data; YY-Y and ZY-P offer useful suggestions in the manuscript revision; Y-Y, TF-Y, DS-Z, and XC-W design the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read the final manuscript and approved the submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Competing of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article forpublication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

†MingGang Zhang and **aoLi Liu will handle correspondence at all stages of refereeing and publication, also post-publication.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Liu, X., **a, W. et al. Network Analysis of Childhood Maltreatment, Anxiety, and Addictive Non-Suicidal Self-injury in Adolescents. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01344-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01344-7