Abstract

Purpose

Patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) may experience sickle cell-related pain crises, also referred to as vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs), which are a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality. The study explored how VOC frequency and severity impacts health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and work productivity.

Methods

Three hundred and three adults with SCD who completed an online survey were included in the analysis. Patients answered questions regarding their experience with SCD and VOCs, and completed the Adult Sickle Cell Quality of Life Measurement Information System (ASCQ-Me) and the Workplace Productivity and Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem (WPAI:SHP). Differences in ASCQ-Me and WPAI:SHP domains were assessed according to VOC frequency and severity.

Results

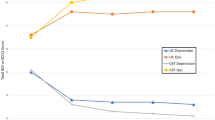

Nearly half of the patient sample (47.2%) experienced ≥ 4 VOCs in the past 12 months. The most commonly reported barriers to receiving care for SCD included discrimination by or trouble trusting healthcare professionals (39.6%, 33.3%, respectively), limited access to treatment centers (38.9%), and difficulty affording services (29.4%). Patients with more frequent VOCs reported greater impacts on emotion, social functioning, stiffness, sleep and pain, and greater absenteeism, overall productivity loss, and activity impairment than patients with less frequent VOCs (P < 0.05). Significant impacts on HRQoL and work productivity were also observed when stratifying by VOC severity (P < 0.05 for all ASCQ-Me and WPAI domains, except for presenteeism).

Conclusions

Results from the survey indicated that patients with SCD who had more frequent or severe VOCs experienced deficits in multiple domains of HRQoL and work productivity. Future research should examine the longitudinal relationship between these outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a hemoglobinopathy that causes red blood cells to lose their oxygen carrying capacity and is associated with severe, systemic vascular complications. It is estimated that approximately 100,000 Americans have SCD [1]. Patients with SCD experience chronic pain, cardiovascular events, ulcers, fatigue, organ damage, and sickle cell-related pain crises, also referred to as vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs). Treatments used to manage symptoms or reduce complications of SCD include hydroxyurea, l-glutamine, and blood transfusions [2]; currently, the only available cure for SCD is bone marrow transplant [3].

Previous research has provided insight into many of the ways in which patients are impacted by SCD [4]. For example, patients with SCD report experiencing sleep disturbances [5], as well as deficits in both physical and mental well-being [6]. The extensive burden of SCD may also lead to an inability to maintain consistent work or schooling, engage in daily, social, or recreational activities, and participate in family life [7,8,9,10]. In addition to the burden of SCD, the experience of VOCs also has detrimental impacts on the lives of patients, though these impacts have been less comprehensively studied. VOCs are caused by multi-cell adhesion or cell clusters that block or reduce blood flow, and are a substantial cause of morbidity in patients with SCD; severe crises have also been associated with increased mortality [11]. These events are unpredictable and can cause disruption and hardship in the lives of patients, sometimes requiring medical attention in emergency departments or sickle cell urgent care centers, or leading to inpatient hospitalization [12]. Previous occurrence of VOCs has been linked to deficits in domains of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) such as general health, vitality, and bodily pain [6].

SCD is associated with high healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), with VOCs being the most common cause of hospital and emergency department visits among patients with SCD [13]. High rates of HCRU have been linked to a variety of poor outcomes among patients with SCD, including lower HRQoL and likelihood of unemployment [14,15,16,17]. Despite high HCRU, especially for acute treatment of VOCs [29], and by patients who have recently completed treatment for breast cancer (21–25%) [30], but slightly less than the absenteeism reported by patients who currently have breast cancer (56–61%) [30]. Absenteeism is calculated as the number of work hours missed, divided by the total number of hours a patient could have worked. Thus, an absenteeism score of 34.99 (the average score of patients with the most frequent VOCs) is generally equivalent to missing 14 h of a 40-h work week, while an absenteeism score of 39.59 (the average score of patients with the most severe VOCs) is generally equivalent to missing 16 h of a 40-h week. Put this way, the impacts of VOCs can be described more concretely, elucidating the ways in which employed patients with frequent or severe VOCs are impacted by SCD.

Given the degree of work impairment experienced by patients with SCD, and in particular by those with more frequent or severe VOCs, it is unsurprising that many patients also reported experiencing negative impacts on their overall employment status. Previous qualitative work has reported that patients with SCD find it difficult to manage their jobs. For example, the FDA’s Voice of the Patient report describes that patients with SCD experience difficulty kee** up with their work due to both absences from work and stress caused by various aspects of the disease [20]. Other qualitative research has documented patients’ descriptions of challenges related to finding and maintaining adequate employment; patients discussed difficulty kee** jobs or building job history, and having to leave jobs that were too physically demanding [10]. Our results extend these findings by hel** to quantify the frequency with which patients experience such impacts, showing that such experiences are relatively widespread among patients with SCD. Similar to the impacts on employment, patients in our study also reported that their SCD had impacted their personal relationships and negatively impacted their education. Overall, the number of patients who experienced negative impacts on education was fewer than those who experienced negative impacts on employment. Patients with SCD often experience a difficult transition from pediatric to adult care [31], and may struggle to obtain consistent and effective care as young adults, thus potentially increasing the likelihood that SCD will negatively affect various facets of their adult lives. Indeed, approximately 75% of the patients in this study reported experiencing barriers to receiving care for their SCD, such as difficulty affording healthcare services, limited health insurance, discrimination by healthcare professionals, difficulty trusting healthcare professionals, and a lack of specialized treatment centers. Increasing access, options, and quality of SCD-related care may improve patients’ employment-related outcomes.

This study had some limitations. As with any information collected through patient report, recall bias could affect reports of events. Second, diagnosis of SCD was entirely self-reported. While recruitment of patients through collaboration with SCD-related organizations and advocacy groups in the absence of explicit physician confirmation has been reported elsewhere [32, 33], the trade-offs between relying on self-report (e.g., more expedient data collection, ability to recruit across a broad geographic region) and obtaining additional confirmation must be considered. Third, selection bias could affect the type of patients who participated in the survey; the survey could only be completed by individuals with internet access, and those who are unfamiliar or less comfortable using this type of technology may have been less likely to participate. Fourth, the study was designed to be cross-sectional, exploratory, and largely descriptive. As such, none of the relationships reported here can be interpreted as causal, nor can longitudinal relationships be inferred. However, the results of the study are informative in their own right and can provide a solid foundation for additional future research.

Balancing the aforementioned limitations, this study also had several particular strengths. First, the study sample was quite large, particularly for a rare disease. Second, evaluation of the study sample strongly suggests that it is generally representative of the larger SCD patient population. While more women than men completed the survey, scores obtained on the ASCQ-Me were nearly identical to those from an SCD benchmark population [23], and the distribution of patients across race, types of SCD, and across US geographic regions is similar to what has been reported in previous studies [34]. Third, the survey assessed a variety of different concepts related to the experience of patients with SCD, including both validated patient-reported outcome measures and items written specifically for this study. This approach allowed for a clearer assessment of the ways in which patients are impacted by the disease. For example, only relying on the WPAI to measure work-related outcomes would capture the experiences only of patients who were currently employed, failing to take into consideration the perspectives of unemployed patients, who comprised 61% of the total study sample. Rather, the WPAI was fielded in conjunction with a series of items regarding the lifetime experiences of all patients, regardless of current employment status, thus providing a more complete understanding of this particular outcome.

This study provides evidence to demonstrate a link between patient outcomes such as HRQoL and work impairment, and the frequency and severity of VOCs. The findings presented in this study provide a solid foundation for future research, which should aim to investigate a causal relationship between these factors. Additional research should also explore how health interventions or the alleviation of structural or environmental barriers to receiving healthcare may improve HRQoL and employment opportunities among patients with SCD.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive description of the patient experience with SCD, with a specific emphasis on highlighting the ways in which VOC frequency and severity impact patients’ HRQoL and work productivity. This research provides evidence to suggest that VOCs may have broad and cumulative impact on aspects of life such as emotional and social functioning which may last beyond the end of the event itself.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Sickle cell disease. Retrieved 11 April 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/treatments.html.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2014). Evidence-based management of sickle cell disease: Expert panel report. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/all-publications-and-resources/evidence-based-management-sickle-cell-disease-expert-0.

Bolaños-Meade, J., & Brodsky, R. A. (2009). Blood and marrow transplantation for sickle cell disease: Overcoming barriers to success. Current Opinion in Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCO.0b013e328324ba04.

Panepinto, J. A., & Bonner, M. (2012). Health-related quality of life in sickle cell disease: Past, present, and future. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24176.

Wallen, G. R., Minniti, C. P., Krumlauf, M., Eckes, E., Allen, D., Oguhebe, A., et al. (2014). Sleep disturbance, depression and pain in adults with sickle cell disease. BMC Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-207.

Dampier, C., LeBeau, P., Rhee, S., Lieff, S., Kesler, K., Ballas, S., et al. (2011). Health-related quality of life in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD): A report from the comprehensive sickle cell centers clinical trial consortium. American Journal of Hematology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21905.

Fuggle, P., Shand, P. A., Gill, L. J., & Davies, S. C. (1996). Pain, quality of life, and co** in sickle cell disease. Archives of Disease in Childhood,75(3), 199–203.

Badawy, S. M., Thompson, A. A., Lai, J.-S., Penedo, F. J., Rychlik, K., & Liem, R. I. (2017). Adherence to hydroxyurea, health-related quality of life domains, and patients' perceptions of sickle cell disease and hydroxyurea: A cross-sectional study in adolescents and young adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0713-x.

Badawy, S. M., Thompson, A. A., Penedo, F. J., Lai, J.-S., Rychlik, K., & Liem, R. I. (2017). Barriers to hydroxyurea adherence and health-related quality of life in adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease. European Journal of Haematology. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.12878.

Matthie, N., Hamilton, J., Wells, D., & Jenerette, C. (2016). Perceptions of young adults with sickle cell disease concerning their disease experience. Journal of Advanced Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12760.

Darbari, D. S., Wang, Z., Kwak, M., Hildesheim, M., Nichols, J., Allen, D., et al. (2013). Severe painful vaso-occlusive crises and mortality in a contemporary adult sickle cell anemia cohort study. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079923.

Brousseau, D. C., Owens, P. L., Mosso, A. L., Panepinto, J. A., & Steiner, C. A. (2010). Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA . https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.378.

Ballas, S. K., & Lusardi, M. (2005). Hospital readmission for adult acute sickle cell painful episodes: Frequency, etiology, and prognostic significance. American Journal of Hematology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.20336.

Carroll, C. P., Cichowitz, C., Yu, T., Olagbaju, Y. O., Nelson, J. A., Campbell, T., et al. (2018). Predictors of acute care utilization and acute pain treatment outcomes in adults with sickle cell disease: The role of non-hematologic characteristics and baseline chronic opioid dose. American Journal of Hematology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.25168.

Williams, H., Silva, S., Cline, D., Freiermuth, C., & Tanabe, P. (2018). Social and behavioral factors in sickle cell disease: Employment predicts decreased health care utilization. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2018.0060.

Badawy, S. M., Thompson, A. A., Lai, J.-S., Penedo, F. J., Rychlik, K., & Liem, R. I. (2017). Health-related quality of life and adherence to hydroxyurea in adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26369.

Badawy, S. M., Thompson, A. A., Holl, J. L., Penedo, F. J., & Liem, R. I. (2018). Healthcare utilization and hydroxyurea adherence in youth with sickle cell disease. Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1080/08880018.2018.1505988.

Shah, N., Bhor, M., **e, L., Paulose, J., & Yuce, H. (2019). Sickle cell disease complications: Prevalence and resource utilization. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214355.

Treadwell, M., Telfair, J., Gibson, R. W., Johnson, S., & Osunkwo, I. (2011). Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: Establishing evidence-based practice and directions for research. American Journal of Hematology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21880.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2014). The voice of the patient: Sickle cell disease: A series of reports from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative. Retrieved 15 February, 2019, from https://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/PrescriptionDrugUserFee/UCM418430.pdf.

Smith, W. R., Penberthy, L. T., Bovbjerg, V. E., McClish, D. K., Roberts, J. D., Dahman, B., et al. (2008). Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00004.

Maxwell, K., Streetly, A., & Bevan, D. (1999). Experiences of hospital care and treatment seeking for pain from sickle cell disease: Qualitative study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7198.1585.

Keller, S., Yang, M., Evensen, C., & Cowans, T. (2017). ASCQ-Me user’s manual. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research.

Keller, S. D., Yang, M., Treadwell, M. J., Werner, E. M., & Hassell, K. L. (2014). Patient reports of health outcome for adults living with sickle cell disease: Development and testing of the ASCQ-Me item banks. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-014-0125-0.

Keller, S., Yang, M., Treadwell, M. J., & Hassell, K. L. (2017). Sensitivity of alternative measures of functioning and wellbeing for adults with sickle cell disease: Comparison of PROMIS® to ASCQ-Me℠. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0661-5.

Cooper, O., McBain, H., Tangayi, S., Telfer, P., Tsitsikas, D., Yardumian, A., et al. (2019). Psychometric analysis of the adult sickle cell quality of life measurement information system (ACSQ-Me) in a UK population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1136-7.

Reilly, M. C., Zbrozek, A. S., & Dukes, E. (1993). The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment measure. PharmacoEconomics,4(5), 353–365.

Revicki, D., Hays, R. D., Cella, D., & Sloan, J. (2008). Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012.

Kronborg, C., Handberg, G., & Axelsen, F. (2009). Health care costs, work productivity and activity impairment in non-malignant chronic pain patients. The European Journal of Health Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-008-0096-3.

Frederix, G. W. J., Quadri, N., Hövels, A. M., van de Wetering, F. T., Tamminga, H., Schellens, J. H. M., et al. (2013). Utility and work productivity data for economic evaluation of breast cancer therapies in the Netherlands and Sweden. Clinical Therapeutics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.03.009.

Jenerette, C. M., & Brewer, C. (2010). Health-related stigma in young adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of the National Medical Association,102(11), 1050–1055.

Adegbola, M. (2011). Spirituality, self-efficacy, and quality of life among adults with sickle cell disease. Southern Online Journal of Nursing Research, 11(1).

Treadwell, M. J., Hassell, K., Levine, R., & Keller, S. (2014). Adult sickle cell quality-of-life measurement information system (ASCQ-Me): Conceptual model based on review of the literature and formative research. The Clinical Journal of Pain. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000054.

Hassell, K. L. (2010). Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the US. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022.

Funding

This study was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

AAR, XL, KLM, and MKW are full-time employees of Optum and received research funding from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation to conduct the study. MB, JP, and SN are full-time employees of the study sponsor, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; MB and JP also own stock in the company. LBH has received funding from the study sponsor, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, and from Bluebird Bio and Pfizer Inc. RH has nothing to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The informed consent form, protocol, and recruitment materials were approved by the New England Independent Review Board (IRB # 120180240). All participants provided consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rizio, A.A., Bhor, M., Lin, X. et al. The relationship between frequency and severity of vaso-occlusive crises and health-related quality of life and work productivity in adults with sickle cell disease. Qual Life Res 29, 1533–1547 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02412-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02412-5