Abstract

Habitat structure can profoundly influence interaction strengths between predators and prey. Spatio-temporal habitat structure in temporary wetland ecosystems is particularly variable because of fluctuations in water levels and vegetation colonisation dynamics. Demographic characteristics within animal populations may also alter the influence of habitat structure on biotic interactions, but have remained untested. Here, we investigate the influence of vegetation habitat structure on the consumption of larval mosquito prey by the calanoid copepod Lovenula raynerae, a temporary pond specialist. Increased habitat complexity reduced predation, and gravid female copepods were generally more voracious than male copepods in simplified habitats. However, sexes were more similar as habitat complexity increased. Type II functional responses were exhibited by the copepods irrespective of habitat complexity and sex, owing to consistent high prey acquisition at low prey densities. Attack rates by copepods were relatively unaffected by the complexity gradient, whilst handling times lengthened under more complex environments in gravid female copepods. We demonstrate emergent effects of habitat complexity across species demographics, with predation by males more robust to differences in habitat complexity than females. For ecosystems such as temporary ponds where sex-skewed predator ratios develop, our laboratory findings suggest habitat complexity and sex demographics mediate prey risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Predation is a key structuring force within ecosystems and often regulates the stability and diversity of communities (Dayton, 1971; Paine, 1980; Sih et al., 1985). The implications of predator–prey dynamics are multifaceted, with both direct lethal (density-mediated) and non-lethal (trait-mediated) effects of predators identified as important ecosystem-level processes (Dodson, 1974; Lima, 1998; Alexander et al., 2013b). Predation pressure can, however, vary markedly over space and time, yet the mechanistic drivers of such variations remain poorly understood (Delclos & Rudolf, 2011; Cuthbert et al., 2018d, 2019c). In particular, habitat structure may differ considerably across spatio-temporal gradients and is known to be an important determinant of interaction strengths through, for example, the provision of prey refugia and mediation of predator–predator interference (Crowder & Cropper, 1982; Barrios-O’Neill et al., 2015; Cuthbert et al., 2018e, 2019a). Furthermore, heterogeneity within populations (e.g. ontogenic or sex ratio change) can alter the intensity of predator–prey interactions (Delclos & Rudolf, 2011; Alexander et al., 2013a; Cuthbert et al., 2019c). However, whether such intraspecific demographic heterogeneity alters the influence of environmental context, such as habitat structure, on interaction strengths remains unclear.

The structuring of habitats in temporary freshwater ecosystems is particularly dynamic, owing to natural variability in water depth and vegetation structure over the hydroperiod. Temporary pond ecosystems provide important aquatic habitats for a variety of amphibians, birds and invertebrates (McCulloch et al., 2003; Ferreira et al., 2012) and are characteristically inhabited by specialist, often endemic, species adapted to withstand extended dry periods (De Meester et al., 2005). In comparison with permanent freshwaters, temporary wetland ecosystems are poorly understood and remain at risk of degradation or destruction as a result of multiple anthropogenic stressors (Dalu et al., 2017a). Accordingly, there is an urgent need to examine biotic interactions in these systems in order to better understand their stability in the context of ongoing environmental change. Moreover, understanding how habitat heterogeneity affects different population demographics is important for understanding population success and ecosystem stability (Kiørboe, 2006).

Animal population demographics are extremely variable over the course of the hydroperiod in temporary ponds (Wasserman et al., 2018b), with the potential to alter offtake rates towards lower trophic groups (Cuthbert et al., 2019c). For copepods, sex-skewed ratios often emerge in natural populations due to processes such as predation and physico-chemical variation (Gusmão et al., 2009; Wasserman et al., 2018b). Zooplankters such as calanoid copepods are numerically dominant in temporary wetland ecosystems for much of the hydroperiod, given their internal recruitment following submersion from egg banks deposited within substrate (Wasserman et al., 2016a). As a result, large predatory copepods can occupy the top trophic levels in these systems in the early stages of the hydroperiod (Dalu et al., 2016), with other higher-order predation extensively dependent on external recruitment dynamics at the landscape scale (e.g. Wasserman et al., 2018b). Intraspecific behavioural variations between sexes in copepod populations are marked, with males often more motile than females due to mate-searching processes and time limitations to reproduction (Kiørboe, 2006; Gusmão et al., 2009). There has, however, been no consideration for whether habitat heterogeneity effects (i.e. habitat structure) manifest differently among demographic subsets of populations (i.e. according to sex variations). Consequently, our understanding of the context dependency of biotic interaction strengths in temporary ponds is lacking, particularly given the documented development of sex-skewed populations in these ecosystems (Wasserman et al., 2018b).

Functional responses are fundamental to derivations of consumer–resource interactions (Solomon, 1949; Holling, 1959). Through quantifications of resource utilisation as a function of resource density, applications of the functional response offer insights into biotic interaction strengths in the context of population-level stability (Alexander et al., 2012; Dick et al., 2014). Furthermore, the functional response approach allows for explicit consideration of multiple context dependencies which may alter consumer–resource interactions, including temperature (Wasserman et al., 2018a), species demographics (Cuthbert et al., 2019c) and multiple predator interactions (Wasserman et al., 2016b; Sentis & Boukal, 2018). Functional responses are typically characterised into three forms (Hassell, 1978), with each, theoretically, pertaining to different consumer–resource outcomes. Type I functional responses are linear and density-independent and are considered mechanistically exclusive to filter feeding organisms (Jeschke et al., 2004). Type II functional responses are hyperbolic and inversely density-dependent, characterised by high consumption rates at low resource (e.g. prey) densities, whereby most, if not all, prey are consumed. Consumption rates then decelerate towards an upper asymptote. Type III functional responses are sigmoidal and density-dependent and are often driven by interactions which require significant search time when resources are rare. Here, the consumption rate initially increases before again reaching a plateau, similar to the Type II functional response. Importantly, the functional response form of consumers may be an important indicator for the stability of interactions, whereby Type II functional responses are typically considered destabilising and Type III, conversely, considered stabilising for resource populations. Moreover, it is known that environmental context (e.g. habitat structure) can impart stability to populations through mediation of more stable functional response forms (e.g. Alexander et al., 2012).

The aim of this study is to use predatory functional responses to quantify combined abiotic and biotic context dependencies of interaction strengths by an important temporary pond specialist. We focus on interactions between the copepod Lovenula raynerae, which is known to be a top predator for much of the hydroperiod before other predators (e.g. notonectids) colonise (Dalu et al., 2017b), and mosquito larval prey, which are known to externally colonise temporary aquatic systems. Previous research has demonstrated the potential role of mosquito prey in the diet of L. raynerae (Cuthbert et al., 2018b, 2019d). Specifically, we aim to decipher the effects of habitat structure and population sex demographics on biotic interactions, and whether the influence of habitat structure is dependent on the internal demographic characteristics within species. Through a factorial laboratory-based approach, we provide comparative insights into the trophic dynamics of poorly understood temporary pond ecosystems.

Methods

Animal collection and maintenance

The focal predators, adult L. raynerae were collected from a temporary pond close to Peddie (33°12′46.9″ S 27°20′11.2″ E), Eastern Cape, South Africa, using a 64-μm mesh zooplankton net and transported in source water to a constant environment (CE) room at Rhodes University, Grahamstown. Adult females and males (total length ± SE: females, 4.39 ± 0.08 mm; males, 4.13 ± 0.08 mm) were maintained in the CE room at 25 ± 1°C and under a 12:12 light:dark regime for 48 h and starved in continuously aerated 30-l tanks containing dechlorinated tap water. The focal prey, larval Culex pipiens complex mosquitoes were cultured using egg rafts collected from artificial containers within the Rhodes University campus and reared to the desired size class (see below) in the same laboratory using a diet of crushed rabbit pellets (Agricol, Port Elizabeth), supplied ad libitum.

Experimental design

Either gravid adult females or males were used in the experiment under three habitat complexity treatments. Habitat complexity was created by positioning rinsed stalks of the bulrush Schoenoplectus brachyceras (Hochst. ex A. Rich.) Lye (4–6 mm dia.) in a uniform array in experimental arenas. Low complexity comprised no stalks, medium complexity two stalks and high complexity four stalks (as per Cuthbert et al., 2019a). This complexity variation represents that displayed throughout the hydroperiod in temporary systems. Second and third instar C. pipiens complex larvae (total length ± SE: 2.87 ± 0.19 mm) were established at five prey densities (2, 4, 8, 16, 32; n = 4 per density) in 80 mL arenas of 5.6 cm diameter containing dechlorinated tap water from a continuously aerated source, 2 hours before the addition of predators. Once predators were added, they were allowed to feed undisturbed for 6 h, after which they were removed and remaining prey counted to derive numbers killed. Controls consisted of four replicates at each density and habitat treatment without predators.

Data analyses

All statistical analyses were undertaken in R v3.5.1 (R Core Development Team, 2018). Generalised linear models (GLMs) assuming a Poisson error distribution and log link were used to analyse overall prey consumption with respect to the ‘habitat complexity’, ‘predator type’ and ‘prey supply’ factors and their two- and three-way interactions. We did not find any evidence for residual overdispersion in the model. An information theoretic approach was followed to evaluate variables of most importance in influencing numbers of prey eaten, with model averaging via second-order Akaike’s Information Criterion (AICc; adjusted for small sample size, Burnham & Anderson, 2002) applied to identify models which minimised information loss (Bartoń, 2015). The relative variable importance (RVI) was also calculated, based on the sum of AICc weights which included the focal predictor variable. Models with ΔAICc < 2 were considered interchangeable. In the top model, effect sizes were derived through analysis of deviance, with Tukey’s tests used post hoc for multiple pairwise comparisons using the ‘multcomp’ package in R (Hothorn et al., 2008). Statistical significance was considered at the 95% confidence interval.

Functional response analyses were undertaken phenomenologically (Pritchard et al., 2017). Accordingly, given that we did not empirically measure the functional response parameters (Jeschke et al., 2002), functional responses were not interpreted mechanistically and were instead used for comparative purposes among factorial experimental treatments (Alexander et al., 2012). Logistic regression considering the proportion of prey consumed as a function of prey density was used to infer FR types. A Type II functional response is characterised by a significantly negative first-order term, whilst a Type III functional response is characterised by a significantly positive first-order term followed by a significantly negative second-order term (Solomon, 1949; Holling, 1959; Juliano, 2001). As prey were not replaced as they were consumed, we applied Rogers’ random predator equation for depleting prey densities (Rogers, 1972; Trexler et al., 1988; Juliano, 2001):

where Ne is the number of prey eaten, N0 is the initial density of prey, a is the attack constant, h is the handling time and T is the total experimental period. The Lambert W function was used to aid model fitting, owing to the implicit nature of Eq. 1 (Bolker 2008). The attack rate parameter corresponds to the initial slope of functional response curves (Hassell & May, 1973; Jeschke et al., 2002), and thus, predators which consume more prey at low prey densities should have a higher attack rate. The handling time parameter, reciprocally (1/h), corresponds to the maximum feeding rate of a predator and the height of functional response curves (Jeschke et al., 2002). Functional response parameters (attack rate, handling time) were non-parametrically bootstrapped (n = 2000) and parameters were compared based on overlap** of 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals across treatments. Given that bootstrap** allows for data to be considered in population terms, rather than at the sample level, a lack of convergence in confidence intervals allows for differences in functional response parameters to be inferred without additional statistical testing.

Results

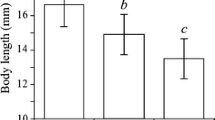

Survival in predator-free controls exceeded 99% and so all experimental mortality was attributed to copepod predation. The ‘habitat’ (RVI = 1.00), ‘predator’ (RVI = 0.78), ‘supply’ (RVI = 1.00) and ‘habitat × predator’ (RVI = 0.40) terms were included in the top model (Table 1). Overall, predation increased significantly under greater prey supplies (χ2 = 152.52, df = 4, P < 0.001) and was significantly affected by habitat complexity (χ2 = 16.12, df = 2, P < 0.001). Significantly greater predation was exhibited under the low complexity treatment compared to the high complexity (P < 0.001) and medium complexity treatment (P < 0.01); there was no significant difference between the medium and high complexity treatments (P = NS). Overall predation was not affected by predator sex (χ2 = 3.38, df = 1, P = NS); however, gravid female copepods tended to consume more than males overall (Fig. 1). The effects of habitat complexity were consistent between predator types as there was no significant ‘habitat × predator’ interaction effect (χ2 = 4.86, df = 2, P = NS); however, consumption by female copepods was generally most affected by increases in habitat complexity (Fig. 1). Indeed, post hoc contrasts indicated that consumption by males was not significantly affected by habitat complexity (all P = NS), whilst consumption by females was significantly greater under low as compared to medium (P < 0.01) and high (P < 0.001) complexities.

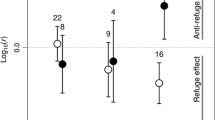

Type II functional responses were observed across each habitat complexity treatment and predator sex (Table 2; Fig. 1). Functional response parameters of female and male copepods showed subtle differences across the habitat complexity gradient (Fig. 2). For female copepods, attack rates were similar across the different levels of habitat; however, these tended to be greater under higher complexities (Table 2; Fig. 1). This was further evidenced by overlap** of confidence intervals between these treatment groups (Fig. 2a). Similarly, whilst habitat complexity had little effect on the attack rates of male copepods (Fig. 1), attack rates trended towards being higher under more complex treatments (Fig. 2a). Generally, there were negligible differences between attack rates of female and male copepods across the habitat types, as indicated by extensive confidence interval overlap.

Handling times and, inversely, maximum feeding rates of female copepods varied across the habitat complexity gradients (Table 2; Fig. 1). Handling times were lowest, and therefore maximum feeding rates were highest, under the low complexity treatment as compared to medium and high habitat complexities (Fig. 1). This significant difference was further evidenced by a lack of overlap in confidence intervals between the low and high complexity treatments for female copepods, whilst medium complexity confidence intervals bridged these treatment groups (Fig. 2b). For male copepods, handling times were similar across the habitat gradient, and thus, maximum feeding rates were relatively unaffected for this predator group (Table 2; Fig. 1). Whilst handling times tended to be longer under higher complexity treatment groups, confidence intervals overlapped across all treatments and thus differences were non-significant for this copepod sex (Fig. 2b). At low complexities, handling times of female copepods were substantially lower than males and generally became more similar as habitat complexity increased; however, confidence intervals of males overlapped with all female copepod complexity groups, owing to extensive interval limits.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates the combined influence of habitat structure and population sex demographics on predator–prey interaction strengths between temporary pond specialist biota. Temporary ponds are particularly dynamic aquatic habitats, with substantial habitat heterogeneity present over short timescales due to characteristic hydroperiod variation (Wasserman et al., 2016c). However, hitherto, there has been little consideration for the influence of environmental variables on interactions in these systems (but see Wasserman et al., 2016c; Cuthbert et al., 2019a), and so, our understandings of temporary wetland ecology and the potential effects of environmental change on species interactions are limited. Furthermore, sex demographics are known to shift radically over the course of the hydroperiod due to selective processes such as predation in temporary ponds (Wasserman et al., 2018b), and the implications of sex ratio variations for trophic interactions in such wetlands remain unclear (but see Cuthbert et al., 2019c). Here, we demonstrate that habitat complexity alters the interaction strength between temporary pond specialists and their prey, but that the effects of habitat structure on these interactions manifest differently between sexes.

Both males and females of the predaceous calanoid copepod L. raynerae were capable of capturing and handling larval mosquito prey across the habitat complexity gradient in the present study. However, consumption was significantly affected by habitat complexity. Specifically, increasing habitat complexity tended to reduce interaction strengths towards larval mosquito prey, yet only significantly for female copepods. Whilst results of laboratory experiments must be viewed with caution when making real-world inferences, comparative laboratory feeding studies can provide useful and robust insights into the effects of multiple treatments in controlled environments which corroborate field patterns (Dick et al., 2014). Complex habitats can provide refugia for prey items and act as a barrier to predator movements (Sih et al., 1992; Barrios-O’Neill et al., 2015). However, the presence of habitat can also intensify interaction strengths, depending on the specific prey capture strategies of predators (Wasserman et al., 2016c). This may be particularly true for ambush predators, which perform better in structured habitats owing to sit-and-wait strategies (James & Heck, 1994). Therefore, habitat implications for biotic interactions such as predation are system-specific. Copepods are often reliant on hydromechanical rather than visual cues for prey detection (Hwang & Strickler, 2001; Cuthbert et al., 2018a), and L. raynerae predation has been previously shown to be unaffected by variations in water clarity (Cuthbert et al., 2018c). Considering the active searching strategy utilised by L. raynerae through the water column, it is likely that negative consumptive effects driven by habitat structure resulted through interference by structures which impeded prey detection. Further, gravid female L. raynerae tended to be more voracious than males in the present study, an effect likely driven by differences in energy demands in relation to the development of progeny. This intraspecific difference corroborates with results from other zooplankton systems (e.g. Laybourn-Parry et al., 1988; Marten & Reid, 2007; Cuthbert et al., 2019c).

Both female and male L. raynerae exhibited a Type II functional response across the habitat complexity gradient, owing to high rates of consumption at low prey densities. Contrastingly, a multitude of other studies has demonstrated shifts in functional response form associated with environmental context (e.g. Koski & Johnson, 2002; Alexander et al., 2012; South et al., 2018). Type II functional responses are indicative of potential population-destabilising effects and high ecological impact, owing to a lack of consumptive refuge where prey are scarce (Dick et al., 2014). Accordingly, it is possible that predatory zooplankters such as L. raynerae can extirpate prey types such as larval mosquitoes, even where habitats are structurally complex. Despite a lack of effect on functional response types, emergent differences in attack rate and handling time parameters were evident across habitat complexities and between copepod sexes. Attack rates in both sexes were generally similar across the habitat gradient, yet tended to peak under higher complexity levels. Attack rates are classically described as the scaling coefficient of functional responses and therefore influence the initial slope of the functional response curve (Hassell & May, 1973; Jeschke et al., 2002). Accordingly, high attack rates are conducive to high predatory impact at low prey densities (Cuthbert et al., 2018e), and this further supports the lack of habitat effect on low-density prey refugia in the present study. Similarly, Wasserman et al. (2016c) investigated emergent effects between habitat structure and temperature in aquatic systems, wherein notonectid attack rates increased with structural complexity under certain conditions.

Conversely, handling times in the present study differed according to habitat complexity. The handling time of a predator corresponds to the time taken to handle and digest a prey item (Jeschke et al., 2002). Inversely, handling times correspond to the maximum feeding rate (i.e. asymptote) of functional response curves. In this study, for gravid female L. raynerae, handling times were significantly reduced under low complexity treatments as compared to high complexity treatments. Accordingly, higher maximum feeding rates (i.e. functional response asymptotes) were displayed under these conditions by the female copepods. It is likely that lower encounter rates with prey resulted in increased handling times in complex environments, and therefore, maximum feeding rates were reduced. This finding corroborates with Cuthbert et al. (2019a), wherein handling times of notonectids tended to increase, and maximum feeding rates thus fall, under greater habitat complexity levels.

Copepod sex demographics, however, mitigated the influence of habitat complexity on interaction strengths. In the absence of habitat complexity, female copepod's maximum feeding rates were substantially higher than males, which saturated at a lower rate. These effects may be driven by differences in satiation levels between the two predator sexes, with energy demands by females often higher in copepods (e.g. Laybourn-Parry et al., 1988; Cuthbert et al., 2019c). For male L. raynerae, the effects of habitat structure on handling times were less prevalent, and therefore maximum feeding rates remained relatively unaffected. Male copepods are often characterised by mate-searching processes which may impart greater vulnerability to higher-order predation (Kiørboe, 2006, Gusmão et al., 2009), and motility rates in male L. raynerae have been shown to be particularly high and unaffected by higher predator cues (Cuthbert et al., 2019b). Accordingly, it is possible that high motility rates in males reduce the influence of habitat structure on handling times via negations of physical interference by habitat structures. However, further behavioural examinations are required to elucidate this, particularly in natural settings. Furthermore, whilst gravid female L. raynerae are significantly more voracious in the absence of habitat (Cuthbert et al., 2019c), in the present study we demonstrate emergent effects of habitat structure which nullify these demographic differences. Therefore, the influence of habitat structure may be, in turn, dependent on the internal characteristics of populations. Future research to examine how emergent habitat complexities alter interactions between multiple predators would provide further insight into trophic dynamics in temporary ponds, owing to the importance of intraspecific predator–predator interactions for prey risk (Wasserman et al., 2018b).

Robust quantifications of trophic interactions within ecosystems are imperative to understanding the influence of environmental change on ecosystem stability, especially in vulnerable temporary wetlands (Dalu et al., 2017a). In particular, studies such as the present which examine the interactive influence of multiple abiotic and biotic context dependencies are crucial to understanding how predation pressure is affected by environmental context. We therefore demonstrate the importance of considering demographic variations within populations when quantifying the influence of environmental changes, such as habitat alterations, for trophic interactions and population-level stabilities.

References

Alexander, M. E., J. T. A. Dick, N. E. O’Connor, N. R. Haddaway & K. D. Farnsworth, 2012. Functional responses of the intertidal amphipod Echinogammarus marinus: effects of prey supply, model selection and habitat complexity. Marine Ecology Progress Series 468: 191–202.

Alexander, M. E., N. E. O’Connor & J. T. A. Dick, 2013b. Trait-mediated indirect interactions in a marine intertidal system as quantified by functional responses. Oikos 122: 1521–1531.

Alexander, M., J. T. A. Dick & N. E. O’Connor, 2013a. Born to kill: predatory functional responses of the littoral amphipod Echinogammarus marinus Leach throughout its life history. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 439: 92–99.

Barrios-O’Neill, D., J. T. A. Dick, M. C. Emmerson, A. Ricciardi & H. J. MacIsaac, 2015. Predator-free space, functional responses and biological invasions. Functional Ecology 29: 377–384.

Bartoń, K. (2015) MuMIn: Multi-model inference. R package.

Bolker, B. M., 2008. emdbook: Ecological Models and Data in R. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Burnham, K. P. & D. R. Anderson, 2002. Model Selection and Multi-Model Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. Springer, New York.

Crowder, L. B. & W. E. Cooper, 1982. Habitat structural complexity and the interaction between bluegills and their prey. Ecology 63: 1802–1813.

Cuthbert, R. N., A. Callaghan & J. T. A. Dick, 2018a. Dye another day: the predatory impact of cyclopoid copepods on larval mosquito Culex pipiens is unaffected by dyed environments. Journal of Vector Ecology 43: 334–336.

Cuthbert, R. N., T. Dalu, R. J. Wasserman, A. Callaghan, O. L. F. Weyl & J. T. A. Dick, 2018b. Calanoid copepods: an overlooked tool in the control of disease vector mosquitoes. Journal of Medical Entomology 55: 1656–1658.

Cuthbert, R. N., T. Dalu, R. J. Wasserman, N. E. Coughlan, A. Callaghan, O. L. F. Weyl & J. T. A. Dick, 2018c. Muddy waters: efficacious predation of container-breeding mosquitoes by a newly-described calanoid copepod across differential water clarities. Biological Control 127: 25–30.

Cuthbert, R. N., T. Dalu, R. J. Wasserman, J. T. A. Dick, L. Mofu, A. Callaghan & O. L. F. Weyl, 2018d. Intermediate predator naïveté and sex-skewed vulnerability predict the impact of an invasive higher predator. Scientific Reports 8: 14282.

Cuthbert, R. N., J. T. A. Dick & A. Callaghan, 2018e. Interspecific variation, habitat complexity and ovipositional responses modulate the efficacy of cyclopoid copepods in disease vector control. Biological Control 121: 80–87.

Cuthbert, R. N., T. Dalu, R. J. Wasserman, A. Callaghan, O. L. F. Weyl & J. T. A. Dick, 2019a. Using functional responses to quantify notonectid predatory impacts across increasingly complex environments. Acta Oecologica 95: 116–119.

Cuthbert, R. N., T. Dalu, R. J. Wasserman, J. T. A. Dick, A. Callaghan, P. W. Forneman & O. L. F. Weyl, 2019b. Quantifying reproductive state and predator effects on copepod motility in ephemeral ecosystems. Journal of Arid Environments 168: 59–61.

Cuthbert, R. N., T. Dalu, R. J. Wasserman, O. L. F. Weyl, A. Callaghan, W. Froneman & J. T. A. Dick, 2019c. Sex-skewed trophic impacts in ephemeral wetlands. Freshwater Biology 64: 369–370.

Cuthbert, R. N., T. Dalu, R. J. Wasserman, O. L. F. Weyl, P. W. Froneman, A. Callaghan & J. T. A. Dick, 2019d. Lack of prey switching and strong preference for mosquito prey by a temporary pond specialist predator. Ecological Entomology. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12801.

Dalu, T., O. L. F. Weyl, P. W. Froneman & R. J. Wasserman, 2016. Trophic interactions in an austral temperate ephemeral pond inferred using stable isotope analysis. Hydrobiologia 768: 81–94.

Dalu, T., R. J. Wasserman & M. T. B. Dalu, 2017a. Agricultural intensification and drought frequency increases may have landscape-level consequences for ephemeral ecosystems. Global Change Biology 23: 983–985.

Dalu, T., R. J. Wasserman, P. W. Froneman & O. L. F. Weyl, 2017b. Trophic isotopic carbon variation increases with pond’s hydroperiod: evidence from an Austral ephemeral ecosystem. Scientific Reports 7: 1–19.

Dayton, P. K., 1971. Competition, disturbance, and community organization: the provision and subsequent utilisation of space in a rocky shore community. Ecological Monographs 41: 351–389.

De Meester, L., S. Declerck, R. Stoks, G. Louette, F. Van De Meutter, T. De Bie, E. Michels & L. Brendonck, 2005. Ponds and pools as model systems in conservation biology, ecology and evolutionary biology. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 15: 715–725.

Delclos, P. & V. W. Rudolf, 2011. Effects of size structure and habitat complexity on predator–prey interactions. Ecological Entomology 36: 744–750.

Dick, J. T. A., M. E. Alexander, J. M. Jeschke, A. Ricciardi, H. J. MacIsaac, T. B. Robinson, S. Kumschick, O. L. F. Weyl, A. M. Dunn, M. J. Hatcher, R. A. Paterson, K. D. Farnsworth & D. M. Richardson, 2014. Advancing impact prediction and hypothesis testing in invasion ecology using a comparative functional response approach. Biological Invasions 16: 735–753.

Dodson, S. I., 1974. Adaptive change in plankton morphology in response to size-selective predation: a new hypothesis of cyclomorphosis. Limnology and Oceanography 19: 721–729.

Ferreira, M., V. Wepener & J. H. J. Van Vuren, 2012. Aquatic invertebrate communities of perennial pans in Mpumalanga, South Africa: a diversity and functional approach. African Invertebrates 53: 751–768.

Gusmão, L. F. M. & A. D. McKinnon, 2009. Sex ratios, intersexuality and sex change in copepods. Journal of Plankton Research 31: 1101–1117.

Hassell, M. P., 1978. The dynamics of arthropod predator-prey systems. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Hassell, M. P. & R. M. May, 1973. Stability in insect host-parasite models. Journal of Animal Ecology 42: 693–726.

Holling, C. S., 1959. Some characteristics of simple types of predation and parasitism. Canadian Entomologist 91: 385–398.

Hothorn, T., F. Bretz & P. Westfall, 2008. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometrical Journal 50: 346–363.

Hwang, J. S. & J. R. Strickler, 2001. Can copepods differentiate prey from predator hydromechanically? Zoological Studies 40: 1–6.

James, P. L. & K. L. Heck, 1994. The effects of habitat complexity and light intensity on ambush predation within a simulated seagrass habitat. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 176: 187–200.

Jeschke, J. M., M. Kopp & R. Tollrian, 2002. Predator functional responses: discriminating between handling and digesting prey. Ecological Monographs 72: 95–112.

Jeschke, J. M., M. Kopp & R. Tollrian, 2004. Consumer-food systems: why type I functional responses are exclusive to filter feeders. Biological Reviews 79: 337–349.

Juliano, S. A., 2001. Nonlinear curve fitting: predation and functional response curves. In Scheiner, S. M. & J. Gurevitch (eds), Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Kiørboe, T., 2006. Sex, sex-ratios, and the dynamics of pelagic copepod populations. Oecologia 148: 40–50.

Koski, M. L. & B. M. Johnson, 2002. Functional response of kokanee salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) to Daphnia at different light levels. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 59: 707–716.

Laybourn-Parry, J., B. A. Abdullahi & S. V. Tinson, 1988. Temperature-dependent energy partitioning in the benthic copepods Acanthocyclops viridis and Macrocyclops albidus. Canadian Journal of Zoology 66: 2709–2713.

Lima, S. L., 1998. Nonlethal effects in the ecology of predator-prey interactions. BioScience 48: 25–34.

Marten, G. G. & J. W. Reid, 2007. Cyclopoid copepods. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 23: 65–92.

McCulloch, G. P., A. Aebischer & K. Irvine, 2003. Satellite tracking of flamingos in southern Africa: the importance of small wetlands for management and conservation. Oryx 37: 480–483.

Paine, R. T., 1980. Food webs: linkage, interaction strength and community infrastructure. Journal of Animal Ecology 49: 667–685.

Pritchard, D. W., R. A. Paterson, H. C. Bovy & D. Barrios-O’Neill, 2017. Frair: an R package for fitting and comparing consumer functional responses. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 8: 1528–1534.

R Core Development Team (2018) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna.

Rogers, D., 1972. Random search and insect population models. Journal of Animal Ecology 41: 369–383.

Sentis, A. & D. S. Boukal, 2018. On the use of functional responses to quantify emergent multiple predator effects. Scientific Reports 8: 11787.

Sih, A., P. Crowley, M. McPeek, J. Petranka & K. Strohmeier, 1985. Predation, competition and prey communities: a review of field experiments. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 16: 269–311.

Sih, A., L. B. Kats & R. D. Moore, 1992. Effects of predatory sunfish on the density, drift, and refuge use of stream salamander larvae. Ecology 73: 1418–1430.

Solomon, M. E., 1949. The natural control of animal populations. Journal of Animal Ecology 18: 1–35.

South, J., D. Welch, A. Anton, J. D. Sigwart & J. T. A. Dick, 2018. Increasing temperature decreases the predatory effect of the intertidal shanny Lipophrys pholis on an amphipod prey. Journal of Fish Biology 92: 150–164.

Trexler, J. C., C. E. McCulloch & J. Travis, 1988. How can the functional response best be determined? Oecologia 76: 206–214.

Wasserman, R. J., M. E. Alexander, D. Barrios-O’Neill, O. L. F. Weyl & T. Dalu, 2016a. Using functional responses to assess predator hatching phenology implications for pioneering prey in arid temporary pools. Journal of Plankton Research 38: 154–158.

Wasserman, R. J., M. E. Alexander, T. Dalu, B. R. Ellender, H. Kaiser & O. L. F. Weyl, 2016b. Using functional responses to quantify interaction effects among predators. Functional Ecology 30: 1988–1998.

Wasserman, R. J., M. E. Alexander, O. L. F. Weyl, D. Barrios-O’Neill, P. W. Froneman & T. Dalu, 2016c. Emergent effects of structural complexity and temperature on predator-prey interactions. Ecosphere 7: e01239.

Wasserman, R. J., R. N. Cuthbert, M. E. Alexander & T. Dalu, 2018a. Shifting interaction strength between estuarine mysid species across a temperature gradient. Marine Environment Research 140: 390–393.

Wasserman, R. J., M. Weston, O. L. F. Weyl, P. W. Froneman, R. J. Welch, T. J. F. Vink & T. Dalu, 2018b. Sacrificial males: the potential role of copulation and predation in contributing to copepod sex-skewed ratios. Oikos 127: 970–980.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Department for the Economy, Northern Ireland. We extend gratitude to Rhodes University for the provision of laboratory facilities. We acknowledge the use of infrastructure and equipment provided by the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB) Research Platform and the funding channelled through the National Research Foundation—SAIAB Institutional Support system. This study was partially funded by the National Research Foundation —South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology (Inland Fisheries and Freshwater Ecology, Grant No. 110507). We also acknowledge the Natural Environment Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling editor: Dani Boix

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cuthbert, R.N., Dalu, T., Wasserman, R.J. et al. Sex demographics alter the effect of habitat structure on predation by a temporary pond specialist. Hydrobiologia 847, 831–840 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-019-04142-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-019-04142-8