Abstract

We evaluated the acceptability and impact of a web-based PrEP educational video among women (n = 126) by comparing two Planned Parenthood centers: one assigned to a Web Video Condition and one to a Standard Condition. Most women reported the video helped them better understand what PrEP is (92%), how PrEP works (93%), and how to take PrEP (92%). One month post-intervention, more women in the Web Video Condition reported a high level of comfort discussing PrEP with a provider (82% vs. 48%) and commonly thinking about PrEP (36% vs. 4%). No women with linked medical records initiated PrEP during 1-year follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Limited levels of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness and uptake among individuals who stand to benefit from PrEP [1,2,3] highlight the need for new healthcare-based interventions that broadly educate and empower patients and can be readily integrated into existing health systems. Women especially could benefit from such initiatives given lagging levels of knowledge and uptake relative to men [1,2,3] and inconsistent provider discussion of PrEP with women [4]. It is essential that women-focused educational interventions are acceptable to US Black and Latinx women in particular. Black and Latinx women are respectively 17 and 4 times more likely than White women to acquire HIV in their lifetime [5] and together account for 75% of all new HIV diagnoses among US women [6]. Despite these disparities, in 2016, Black and Latinx women represented only 43% of annual PrEP prescriptions among women, totaling < 1600 PrEP prescriptions nationwide [3].

Electronic delivery of HIV prevention interventions enables broad dissemination of knowledge and requires fewer resources than in-person delivery, while yielding significant effects on sexual health and health behavior [7]. In studies conducted with women, including studies with Black and Latinx women specifically, electronically-delivered HIV prevention interventions have been highly acceptable and similar or superior in efficacy than interventions delivered in person [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. To date, few studies have evaluated electronically-delivered interventions that focus particularly on PrEP education among women [8, 9]. One study evaluated a brief web-based educational video about PrEP among a community-based sample of 116 Black women and found the video to be highly acceptable [8]. Specifically, 78% of women watched the full 9-min video, of whom 89% rated it favorably, 76% reported intention to seek PrEP, and 91% indicated that they would recommend it to others. Among those who would recommend it, reasons given for doing so included knowledge, entertainment, and empowerment conferred by the video. Among those who would not, reasons given included lengthiness and use of animated characters.

Building on earlier work [8,9,10,11,12,13,14], we present findings of an implementation study designed to test the concept of electronic delivery of a web-based PrEP educational video in a reproductive healthcare setting. Specifically, we adapted and disseminated a brief web-based PrEP educational video and evaluated its acceptability and impact among patients relative to PrEP education delivered by a clinician in person. In kee** with participants’ critiques of the web video used in the earlier study [8], our video was shorter in duration (7 vs. 9 min) and included patient actors and a Planned Parenthood clinician rather than animated characters. Additionally, our study was uniquely embedded in a reproductive healthcare context and included a comparison condition, both attitudinal and behavioral evaluation outcomes, and longitudinal follow-up.

We conducted the study with a racially and ethnically diverse sample of sexually active, HIV-negative/status-unknown women engaged in reproductive healthcare at Planned Parenthood and assessed differences across racial/ethnic groups. We evaluated the intervention at three time points: immediately post-intervention via an online patient survey, 1-month post-intervention via an online patient survey, and 1-year post-intervention via patient medical record review. During the immediate post-intervention survey, we evaluated video acceptability (e.g., fit with patients’ learning style, capacity to hold their attention) and perceived impact (e.g., on understanding of PrEP, on interest in PrEP). Across the three time points, we compared the impact of the web video vs. clinician-delivered PrEP education on PrEP-related attitudes (e.g., intention to use PrEP, comfort discussing PrEP with a provider) and behaviors (e.g., talking about PrEP, using PrEP).

Methods

Study Setting and Design

In 2018, two Planned Parenthood centers in Southern New England with similar patient sociodemographic profiles and PrEP prescription histories participated in a 3-month PrEP implementation study. PrEP rollout at both health centers had been gradual over the preceding 2–3 years, during which time clinicians at the two study centers received the same PrEP clinical guidelines and training. In the months immediately preceding study implementation, clinicians at both centers were actively prescribing PrEP, but they were not doing so in a routine or standardized way. Electronic medical record data indicate that over the 3 months preceding study initiation, PrEP was prescribed for a total of 11 patients–nine of whom were men–at both centers combined. During that same period, thousands of patients—most of whom were women—had attended health visits at the two centers. Patients’ insurance status or financial circumstances are not believed to have posed a significant barrier to PrEP prescription for most patients, as there had been resources and staff available on site that could help patients navigate cost at both centers.

Each of the two study conditions was implemented in a separate health center rather than both being implemented within a single center to avoid contamination (e.g., patients who watched the web-based PrEP educational video discussing video content with patients who were assigned to receive standard, clinician-delivered education). During the week immediately preceding the 3-month study implementation period, clinicians participated in a study orientation session held at their center. During both orientation sessions, clinicians were encouraged to routinely inform all patients about PrEP irrespective of the reason for patients’ visits, and they were provided with parallel protocols (see Online Appendix 1).

At one of the two centers (Web Video Condition), an email announcing the availability of PrEP at Planned Parenthood was sent to all patients who had given permission for Planned Parenthood to contact them via email, were 18 years of age or older, and had received care at the center in the preceding year. Email dissemination was not otherwise restricted by behavior, HIV status, gender, or other characteristics. The email linked to a 7-min web video about PrEP (15; description and URL provided below). At the other center (Standard Condition), patients were informed about PrEP only during in-person health visits via clinician-delivered education. Patients in the Standard Condition who met the following screening criteria and expressed interest in learning more about PrEP were invited to participate in the study: age 18 or older; identifies as a woman or female; HIV-negative or unsure of HIV status; and reports vaginal sex, anal sex, or sharing needles/injection equipment in the past 6 months.

Patients at both centers learned of the survey opportunity and associated compensation early in the process of being informed about PrEP. Those who agreed to participate were surveyed online immediately after learning about PrEP. Specifically, they were linked to the online survey directly from the video in the Web Video Condition or emailed the survey link within 48 h of attending the in-person appointment in the Standard Condition. They were also contacted via email to complete a follow-up survey approximately 1 month later. Prior to initiating the first survey, patients were informed of study procedures, risks and benefits, and participant rights as part of an online consent process. The research team requested patients’ permission to link their survey responses to their Planned Parenthood medical records. We subsequently reviewed linked medical records to determine whether participants had obtained a PrEP prescription during the year following the intervention and, if applicable, whether they persisted in using PrEP for six or more months. Patients were compensated for study participation with electronic gift cards.

Video Adaptation

The web video was adapted from an existing PrEP educational video titled “What is PrEP?” [15]. The original video covered basic information about PrEP and included a narrated animation of its effect on the body, along with details about dosing, adherence, and side effects. We adapted the video to increase its relevance to Planned Parenthood of Southern New England’s clientele, approximately 87% of whom are cisgender women. The added content was tailored to cisgender women (e.g., PrEP safety during pregnancy) but was suitable for all genders. Our research team, which included academic researchers and Planned Parenthood clinicians, first compiled a list of potential content changes based on PrEP-related scientific literature and clinical expertise. We elicited patient feedback on video content, including proposed changes, as part of a patient needs assessment survey completed by 221 patients, and we utilized the feedback to create an adapted version of the video. The video was further refined based on feedback provided by Planned Parenthood clinicians and staff members. The final video included the following adaptations: embedded skits of two young women discussing sex and PrEP, voiceover by a Planned Parenthood clinician, information about PrEP use in the context of pregnancy and birth control, information about post-exposure prophylaxis, and contact information for patients’ local Planned Parenthood center (see Online Appendix 2). The final version of the video substituting the general Planned Parenthood website for center-specific contact information is accessible here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1x4KQ9N4xFc.

Measures

All evaluation outcome measures are summarized in Table 1. For most outcomes, response options were recoded into conceptually meaningful categories.

Immediate Post-Intervention Patient Survey Measures

Single-item, self-report measures of video acceptability and perceived impact were administered to participants in the Web Video Condition immediately after watching the video. The measures assessed perceived improvement in understanding what PrEP is, how PrEP works in the body, how to take PrEP as a once-a-day pill, and what side effects are associated with PrEP. Participants also reported whether the video held their attention, whether the video was confusing, and whether they anticipated talking to others about what they learned in the video. Additionally, participants rated perceived impact of the video on PrEP interest, likelihood of using PrEP, and comfort discussing PrEP with a provider.

To evaluate differences in immediate impact between the two conditions, we used single-item, self-report measures to assess interest in learning more about PrEP, intention to use PrEP if available for free, and comfort discussing PrEP with a provider. During the immediate post-intervention survey, participants also reported background characteristics, including sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, employment, and household income), prior PrEP awareness (dichotomized for all analyses as heard of PrEP vs. never heard of PrEP prior to the study), prior PrEP use, and perceived lifetime HIV risk (dichotomized for inferential analyses as not at all likely vs. a little bit, somewhat, very, or extremely likely).

One-Month Post-Intervention Patient Survey Measures

To evaluate differences in impact between the two conditions 1 month post-intervention, we used single-item, self-report measures to assess comfort discussing PrEP with a provider; frequency of thinking about PrEP, seeking further information about PrEP, or talking about PrEP over the past month; talking about PrEP with a provider in particular over the past month; and initiating PrEP use in the past month. Skip patterns were programmed into the survey and data were coded such that if a participant reported never thinking about PrEP, she was assumed not to have searched for more information about PrEP or talked about PrEP, and if a participant reported that she had not spoken to a healthcare provider about PrEP, she was assumed not to have initiated PrEP. These assumptions were established a priori.

One-Year Post-Intervention Electronic Medical Record Measures

PrEP uptake was operationalized as prescription of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate with emtricitabine for a PrEP indication documented within a patient’s Planned Parenthood electronic medical record within 1 year of completing the immediate post-intervention survey. At the time of 1-year follow-up, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate with emtricitabine was the only form of PrEP approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. PrEP persistence was operationalized as PrEP prescription renewal six or more months following first PrEP prescription.

Analyses

To allow for comparison of the two conditions, we restricted the analytic samples to adults 18 years and older who completed the survey and were sexually active (defined as engaging in vaginal or anal sex with a man in the past 6 months), HIV-negative/status-unknown (i.e., reported no prior HIV diagnosis), and self-identified as a “woman” or “transgender woman.” Eligibility had originally been restricted by behavior, HIV status, gender, and age in the Standard Condition but only by age in the Web Video Condition. For analyses of web video acceptability and perceived impact, we calculated frequency distributions to describe the sample and variables of interest.

Chi-square tests were performed to assess racial/ethnic differences for all evaluation outcomes. A low number of observations (expected count < 5 in more than 20% of cells) prohibited chi-square tests of racial/ethnic differences on multiple evaluation measures when race/ethnicity was divided into three or more categories [16]. Therefore, based on racial/ethnic group sizes, we dichotomized race/ethnicity into White (largest group) or Black/Latinx/other. Dichotomizing race/ethnicity resulted in a sufficient number of observations (expected count of five or more in all cells) for chi-square tests to be conducted or, if still insufficient, allowed 2 × 2 Fisher’s two-sided exact tests to be performed for most outcomes [16]. When chi-square tests could be conducted, phi, a measure of the strength of association between two dichotomous variables that adjusts the chi-square statistic to account for sample size, was calculated as an indicator of effect size, with thresholds of 0.1 (small effect), 0.3 (medium effect), and 0.5 (large effect) for 2 × 2 analyses [17].

For comparative analyses of the Web Video Condition and Standard Condition immediately post-intervention and one month later, we calculated frequency distributions for outcomes of interest. When outcome distributions allowed (i.e., there was an expected count of five or more observations in all cells), we conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses to assess significant differences between conditions, which allowed us to adjust for other variables [16]. When logistic regression was possible but there were a limited number of observations in one or more cells, we conducted both regression analyses and Fisher’s two-sided exact tests. When the expected count was < 5 in one or more cells, logistic regression could not be conducted and only Fisher’s two-sided exact tests were performed [16]. In each of our regression models, we initially included race/ethnicity and added a race/ethnicity × condition interaction term to assess partial, conditional, and interaction effects related to race/ethnicity (dichotomized as White vs. Black/Latinx/other). Because race/ethnicity and the race/ethnicity × condition interaction term yielded no significant effects, they were excluded from analyses subsequently reported. For all logistic regression analyses, we report adjusted odds ratios (aORs), adjusting for background characteristics that differed statistically between conditions and/or were associated with one or more evaluation outcomes, as well as prior PrEP awareness due to its conceptual relevance. To describe the 1-year impact of condition on PrEP uptake and persistence, we calculated frequency distributions of evaluation outcomes, which prohibited further comparative analyses.

Results

Study Sample Overview

A total of 165 patients received the intervention and completed the immediate post-intervention survey between January and April of 2018: 106 viewed the video that was electronically disseminated at one center (Web Video Condition) and 59 others were informed about PrEP in person during a health visit at the other center (Standard Condition). The web video URL and accompanying message were emailed to 2811 patients in the Web Video Condition, suggesting a participation rate of 4% based on the number of post-intervention surveys completed. Of the 106 participants in the Web Video Condition, for which study participation was unrestricted by behavior, HIV status, or gender, 76 (72%) were sexually active, HIV-negative/status-unknown women 18 and older and were therefore included in the analytic sample. During in-person screening in the Standard Condition, a total of 170 patients expressed initial interest in learning more about PrEP and agreed to be contacted about the survey via email, of whom 59 (35%) completed the immediate post-intervention survey. Of these 59 participants in the Standard Condition, for which study participation was restricted by behavior, HIV status, and gender as part of an initial screening step, 50 (85%) were sexually active, HIV-negative/status-unknown women 18 and older and were therefore included in the analytic sample.Footnote 1 Thus, in total, 126 sexually active, HIV-negative/status-unknown women participated in the study and were included in the analytic sample: 76 in the Web Video Condition and 50 in the Standard Condition.

Across both study conditions combined, 64 of 126 sexually active, HIV-negative/status-unknown women completed the 1-month follow-up survey. Follow-up survey participants included 39 women in the Web Video Condition (51% of immediate survey-completers), and 25 women in the Standard Condition (50% of immediate survey-completers). Attrition was not significantly different between conditions (X2 [1, N = 126] = 0.02, p = 0.89). Compared with participants who did not complete the 1-month follow-up survey, those who completed were younger (t [124] = − 2.86, p = 0.01), and a higher percentage had a household income below $30,000/year (X2 [1, N = 126] = 7.16, p = 0.01). Completers did not differ significantly from non-completers by gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, employment, prior PrEP awareness/experience, or perceived lifetime HIV risk.

Across both study conditions combined, 54 sexually active, HIV-negative/status-unknown women gave permission to link their survey responses to their Planned Parenthood electronic medical records for monitoring of 1-year outcomes. Linked participants included 34 women in the Web Video Condition (45% of immediate survey-completers) and 20 women in the Standard Condition (40% of immediate survey-completers). There was no significant difference between conditions in the percentage of women permitting linkage to their electronic medical records (X2 [1, N = 126] = 0.28, p = 0.60). There were no significant difference in sociodemographic characteristics or prior PrEP awareness/experience between participants who permitted (vs. did not permit) linkage. A higher percentage of participants who permitted linkage reported perceiving any lifetime risk of acquiring HIV (X2 [1, N = 126] = 3.96, p < 0.05).

Sample Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of study participants who participated in the Web Video and Standard Conditions at each of the three study time points are summarized in Table 2. Sexually active, HIV-negative/status-unknown women in the Web Video Condition (n = 76) did not differ from those in the Standard Condition (n = 50) by sociodemographic characteristics, except that a lower percentage reported being heterosexual (X2 [1, N = 119] = 4.13, p = 0.04). There was a non-significant trend suggesting that women in the Web Video condition were more likely to have prior awareness of PrEP (X2 [1, N = 126] = 2.88, p = 0.09). There was no significant difference in prior PrEP usage or perceived HIV risk.

We compared sociodemographic characteristics of women in our immediate post-intervention analytic sample to the larger populations of women engaged in care at the health centers from which they were recruited. In the Web Video Condition, the percentage of women under 25 was comparable in the analytic sample (47%) vs. population (39%; X2 [1, N = 76] = 2.33, p = 0.13), as was the percentage who were non-Hispanic White (51% vs. 46%; X2 [1, N = 76] = 0.75, p = 0.39). Likewise, in the Standard Condition, the percentage of women under 25 was comparable in the analytic sample (50%) vs. population (45%; X2 [1, N = 50] = 0.45, p = 0.50), as was the percentage who were non-Hispanic White (56% vs. 48%, X2 [1, N = 50] = 1.22, p = 0.27).

Web Video Acceptability and Perceived Impact Immediately Post-Viewing

Web video acceptability outcomes are summarized in Table 3a. Immediately after viewing the video, most women in the analytic sample agreed that the video helped them to better understand PrEP and that they anticipated talking to others about what they learned in the video. After the video, 58% of the women were more interested in PrEP, 57% were more likely to take PrEP, and 79% felt more comfortable talking to a provider about PrEP.

Race/Ethnicity-Based Comparisons

All evaluation outcomes stratified by race/ethnicity are displayed in Table 3a and b. 2 × 2 chi-square tests revealed no significant racial/ethnic differences on any video acceptability or perceived impact measures within the Web Video Condition immediately post-viewing. There was a non-significant, trend-level difference in the percentage of Black/Latinx/other (68%) vs. White (49%) women who reported that the video increased their PrEP interest (X2 [1, N = 76] = 2.77, p < 0.10), with a phi value of 0.19, suggesting a small-to-medium effect size. Chi-square analyses revealed no significant or trend-level racial/ethnic differences in immediate or 1-month outcomes administered in both conditions, with p-values ranging from 0.38 to 0.83. All phi values were < 0.10 with one exception: A phi value of 0.11 suggested a small effect of race/ethnicity on thinking about PrEP, such that a greater percentage of Black/Latinx/other women (28%) than White women (19%) commonly thought about PrEP during the 1-month follow-up period. In adjusted analyses examining the effect of study condition (Web Video vs. Standard Condition) on evaluation outcomes, no significant partial, conditional, or interaction effects of race/ethnicity were detected relative to either immediate or one-month outcomes.

Immediate and 1-Month Comparisons of Web Video Condition vs. Standard Condition

The results of analyses comparing the two study conditions on evaluation outcomes are summarized in Table 4. In multivariable analyses, we adjusted for sexual orientation because it statistically differed between study conditions, perceived lifetime HIV risk because it was statistically associated with one or more outcomes (i.e., PrEP interest; X2 [1, N = 126] = 6.97, p = 0.01), and prior PrEP awareness because of its conceptual relevance. No significant differences emerged between conditions immediately after patients learned about PrEP on any of three outcomes: interest in learning more about PrEP, intention to use PrEP, and comfort discussing PrEP with a provider.

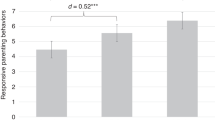

Among the subset of participants who completed the 1-month follow-up survey (n = 64), significant differences were observed between conditions on two of five outcomes: A larger percentage of women in the Web Video Condition (82%) vs. the Standard Condition (48%) reported a high level of comfort discussing PrEP with a provider, and a larger percentage of women in the Web Video Condition (36%) vs. Standard Condition (4%) reported that they commonly thought about PrEP in the preceding month. There was no significant difference in the percentage of Web Video Condition (23%) vs. Standard Condition (16%) participants who commonly sought further information about PrEP. There were non-significant, trend-level differences in the percentage of Web Video Condition (41%) vs. Standard Condition (16%) participants who commonly talked about PrEP and in the percentage of Web Video Condition (15%) vs. Standard Condition (0%) participants who talked about PrEP with a provider in particular. No participants from either condition reported initiating PrEP during the 1-month follow-up period.

One-Year Comparisons of Web Video Condition vs. Standard Condition

Of the 34 sexually active, HIV-negative/status-unknown women in the Web Video Condition who gave permission at baseline for us to link their survey responses to their Planned Parenthood medical records, none obtained a prescription for PrEP at Planned Parenthood during the 1-year follow-up period. Notably, of the larger group of web video viewers with linked records (i.e., not restricted by behavior, HIV status, or gender), two patients obtained a PrEP prescription, both of whom persisted in using PrEP for six or more months. Both identified as gay or bisexual men, one Latinx and the other non-Hispanic White, and neither was aware of PrEP prior to watching the video. Of the 20 sexually active, HIV-negative/status-unknown women in the Standard Condition who gave permission for linkage to their medical record, none obtained a PrEP prescription at Planned Parenthood during the 1-year follow-up period.

Discussion

Electronic dissemination of an educational video offers a straightforward strategy to educate patients about PrEP that requires minimal cost and effort. In this study, the video was well received and similarly effective across racial/ethnic groups. The majority of patients reported that the video improved their understanding of PrEP and increased their PrEP interest, likelihood of taking PrEP, and comfort discussing PrEP with a provider. Additionally, most anticipated discussing what they learned from the video with others.

The web video was at least as effective, and in some ways more effective, than clinician-delivered PrEP education during healthcare visits. Specifically, the web video showed comparable immediate effects on PrEP interest, PrEP intention, and comfort discussing PrEP with a provider. As compared to clinician-delivered education, the video prompted greater PrEP contemplation (i.e., frequency of thinking about PrEP) over the month that followed and was associated with a higher level of comfort discussing PrEP with a provider 1 month post-intervention. The video was also marginally associated with more frequent conversations about PrEP.

In addition, 15% of patients in the Web Video Condition discussed PrEP with a provider compared with 0% in the Standard Condition during the 1-month follow-up period, a finding of marginal significance. When interpreting this marginal difference, it is important to bear in mind that patients in the Standard Condition were recruited during an in-person appointment, at which time they had the opportunity to discuss PrEP with a provider. This initial discussion would not have been captured in the 1-month follow-up period. Therefore, compared with the Web Video Condition patients, Standard Condition patients may have been less inclined to visit a health center again so immediately to discuss PrEP with a provider. They may also have been less likely to seek care for another health concern and discuss PrEP during that visit if existing health concerns had just recently been addressed.

The sample that we recruited was diverse with respect to race and ethnicity, and there were minimal racial/ethnic differences in the acceptability or perceived impact of the web video or the PrEP attitudes and behaviors measured. However, the comparisons by race/ethnicity must be interpreted with caution: Our small sample size necessitated combining racial/ethnic subgroups into fewer racial/ethnic categories for inferential analyses. Such an approach ignores the heterogeneity of these subgroups, and we recognize that a larger sample permitting more nuanced analyses would be preferable. The small sample size also reduced our power to detect significant differences by race/ethnicity. All chi-square tests assessing racial/ethnic differences in evaluation outcomes were non-significant. However, phi values, which adjust chi-square statistics to account for sample size, suggested a small-to-medium effect of race/ethnicity on women’s perceived impact of the video on their PrEP interest (with a greater percentage of racial and ethnic minority women vs. White women perceiving the video to increase their interest in PrEP) and a small effect of race/ethnicity on thinking about PrEP (with a greater percentage of racial and ethnic minority women vs. White women commonly thinking about PrEP during the 1-month follow-up period). Our results tentatively support the web video being similarly acceptable and at least as impactful among racial and ethnic minority women relative to White women. These findings are promising given the disproportionately high rates of HIV among Black and Latinx women and the disproportionately low rates of PrEP use among these groups relative to women of other races [3, 6], which signal a need for HIV preventive interventions that are acceptable and effective for these groups in particular.

Clinical Implications

Both video-based and in-person, clinician-delivered PrEP education are valuable to patient care, as suggested by nearly a third of women in both conditions expressing intention to use PrEP after learning about it. Dissemination of a video should not replace face-to-face discussion of PrEP with providers or shift the onus of initiating patient–provider PrEP discussion onto the patient. Rather, it can supplement and encourage such conversations. For example, a video can illustrate complex concepts that may be valuable to patients’ comprehension and acceptance of PrEP but difficult to understand based on verbal description alone, such as the process by which PrEP interferes with viral replication at a cellular level. Additionally, if patients are given direct access to the video as they were in the current study, they can readily replay the video as frequently as desired. Four out of five study participants who watched the video reported that they were likely to talk to other people about the video; in addition to sharing knowledge gleaned from the video, patients could easily share the video itself. Thus, video-based education could promote snowball dissemination of PrEP knowledge across patients’ social networks, which may be particularly beneficial in communities disproportionately affected by HIV.

The differences that emerged between video-based and clinician-delivered education in the current study may reflect the realities of fast-paced healthcare settings in which routinely delivering 7 min of concentrated PrEP education (i.e., the equivalent of the video) is simply unrealistic for clinicians. Electronic media can be incorporated into healthcare settings in multiple ways to enhance PrEP education and streamline health visits, such as being emailed in advance of pending appointments or included in waiting room video programming. Clinical staff members have previously reported that showing a PrEP educational video in the waiting room of a reproductive health center has helped to orient patients and facilitate efficient discussions with providers [18].

It is encouraging that the video supported PrEP contemplation and sustained comfort discussing PrEP with a provider, both of which could help to advance PrEP uptake. Our finding that none of the women in our study initiated PrEP in the subsequent year suggests that the barriers to PrEP that they perceived ultimately outweighed perceived benefits. Previous research has identified concerns about side effects and safety, out-of-pocket costs, lack of PrEP knowledge, misinformation from healthcare providers, medical mistrust, discomfort communicating with healthcare providers, stigma, pharmacy-related challenges, complexity/burden of the PrEP regimen, and low perceived risk of HIV acquisition to be among the barriers to PrEP that women may experience [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Perceived barriers to PrEP can contribute to persistent “PrEP rumination,” or ongoing thoughtful deliberation that delays or prevents uptake [25]. Although systematic investigation of perceived barriers was beyond the scope of the current study, we know that the majority of our study participants perceived their risk of acquiring HIV to be minimal when surveyed immediately post-intervention, which may have contributed to their decision not to initiate PrEP during the 1-year follow-up period. We speculate that medical mistrust was less likely to be a salient barrier for participants in our care-engaged sample compared with women not accessing care, though medical mistrust could still be present among care-engaged patients and adversely affect patient-provider communication about PrEP [27]. We also speculate that misinformation from healthcare providers was not a significant barrier for participants in our study because of the training that clinicians received prior to study implementation.

An educational video or introductory conversation with a clinician about PrEP may help to initially address some of the barriers to PrEP uptake that women face (e.g., unawareness, concern about side effects). Other forms of intervention can further impact women’s risk–benefit calculus and facilitate movement from PrEP contemplation to uptake. Positive, non-judgmental interactions with healthcare providers that build patients’ confidence in their expertise and comfort communicating with them can promote ongoing conversation about PrEP and subsequent initiation [25]. Endorsement of PrEP and dissemination of information about PrEP by trusted community ambassadors and members of peer networks can strengthen understanding of PrEP and foster confidence in its use [19, 23]. Importantly, these community sources may be primary sources of PrEP information among women not engaged in care [23]. Hearing directly from peers about their experiences taking PrEP could help to allay specific medication-related concerns [19]. In addition, social marketing that reduces HIV- and PrEP-related stigma and communicates the relevance of PrEP to women could help to overcome social challenges and misperceptions on a broader scale [9, 21, 23]. Beyond addressing perceived barriers, PrEP interventions should underscore the prospective benefits of PrEP, which may be similarly or more influential to individuals’ assessment of their own PrEP candidacy [28]. For example, messaging that focuses on autonomy and self-care may be more likely to resonate with women than risk-focused messaging intended to provoke fear [26].

Alone or in combination, the web-based educational video and other PrEP interventions may facilitate PrEP initiation for some people. However, as health professionals, researchers, and advocates, our ultimate objective when disseminating the video was not for all women who viewed it to subsequently initiate PrEP, but rather for all women to be empowered with the knowledge they need to make informed decisions about PrEP and to access it should they choose to do so. Accordingly, that some women did not express intention to use PrEP following video viewing and that all women refrained from initiating it in the year that followed are notable outcomes but not necessarily negative ones.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study has limitations. Because this study was designed as a test of concept and involved only two health centers, our sample size was small. The acceptability and perceived impact of the web video may not be broadly generalizable to transgender women or women living in other geographic locations, not currently engaged in care, or not incentivized to watch the video. Furthermore, the web video would not be a viable intervention for patients who lack the technology (e.g., smartphone, computer) or Internet connectivity (Wi-Fi or cellular data) needed to access the video. Additionally, as noted above, the small sample size limited our capacity to examine racial/ethnic differences in depth and to detect significant differences.

When comparing the two study conditions, we used internal center-level data to select centers with similar patient sociodemographic profiles and PrEP prescription histories and statistically adjusted for significant sociodemographic differences. Nonetheless it is possible that patient-, center-, or city-level differences that were unaccounted for affected results of our comparison. Replication of the study with a cluster-randomized design would strengthen the inferences made here. Additionally, although the study was designed so that, in both conditions, all sexually active, HIV-negative or status-unknown women aged 18 years or older who were engaged in care should have had the opportunity to learn more about PrEP and participate in the study, the reality is that some patients meeting these criteria in both conditions did not. Consequently, the patient samples were not perfectly matched. In the Web Video Condition, patients who did not have a current email address in their medical record or who opted out of receiving email communication from Planned Parenthood would not have been reached. In the Standard Condition, although clinicians/clinical staff were asked to screen all potentially eligible patients during health visits, it is unclear how consistently this directive was followed, and it is possible that time constraints or biases affected their selection of patients for screening. An additional design limitation is the lack of a control condition in which PrEP education was altogether absent. Involving a third condition of women who received neither video- nor clinician-delivered PrEP education could offer insight into the effects of each form of education relative to none.

It is important to note that there was substantial attrition at the 1-month follow-up time point in both conditions, with only 50–51% of immediate survey-completers participating in the 1-month follow-up survey. Although there was no significant difference in attrition between the two conditions and most background characteristics did not differ between participants who completed the follow-up survey and those who did not, participants who completed the follow-up were significantly younger, and a higher percentage had a household income below $30,000/year. Several factors may have contributed to study attrition, such as the amount of compensation attached to survey completion, number of reminder emails sent, and framing of the follow-up survey opportunity. Additionally, only 40–45% of immediate survey completers granted permission to link their surveys to their medical records for our team to obtain 1-year outcome data, which may reflect a desire for anonymity after disclosing private and sensitive information or the absence of further incentivization. Although we consider our use of PrEP prescription data from patients’ electronic medical records to objectively monitor 1-year impact on PrEP uptake to be a strength of the study, such data are not only limited by attrition, but also by the possibility that participants obtained PrEP from another source (e.g., another provider) that was not captured in their Planned Parenthood medical record.

The video adapted for this study proved to be an acceptable and effective means of communication. However, future work might investigate various content and format modifications to the video and corresponding promotional message that could enhance the impact of the video and initial interest in viewing the video. PrEP educational preferences may systematically differ by patient characteristics. The content of our video was tailored to Planned Parenthood’s clientele, which is primarily composed of young cisgender women. However, given that relatability may affect viewer engagement [8], key content included in the video, such as the gender and risk scenario of the patients presented in the opening and closing skits, could be modified to improve relatability for different patient profiles. In addition, the video was intended to be suitable for patients with minimal PrEP knowledge, rendering it appropriate for many of the patients who elected to watch it in our study—68% of women in the Web Video Condition analytic sample had never previously heard of PrEP. However, patients who are already familiar with PrEP and contemplating usage or (dis)continuation may benefit from a video incorporating other information, such as details about local HIV epidemiology, guidance on sexual health communication, or instructions for accessing PrEP financial assistance [9, 14]. Although the majority of participants in the Web Video Condition indicated that the video held their attention, it is possible that expanding the web-based intervention to incorporate not only video viewing but also interactive elements such as games or personalized role plays could promote more active engagement [9, 14]. Future work aimed at tailoring this video or other web-based PrEP educational interventions to optimize impact with a given population may benefit from preliminary assessment of the population’s pre-existing PrEP knowledge and preferences as well as systematic comparison of multiple versions of the intervention in which key elements are varied.

Conclusion

During the current COVID-19 pandemic, when healthcare resources are stretched and it is advantageous to limit the time needed for in-person patient–provider interaction, virtual education is particularly important. Both now and in the post-pandemic era, as telemedicine is increasingly embraced and patients become accustomed to receiving health information electronically, a web-based educational video offers a synergistic addition to existing health services.

In our study, electronic dissemination of a brief educational video showed promise for supporting women’s awareness and consideration of PrEP and the potential to indirectly promote PrEP awareness within the larger community. Many providers throughout the US have not yet adopted PrEP into practice [29], and many who have discussed PrEP with patients have done so on a selective basis. Such a non-standardized approach may contribute to suboptimal PrEP use and access disparities [30], especially among populations with low PrEP awareness and limited outside opportunities to learn about PrEP. At a time when PrEP integration into standard clinical practice is still evolving, tools that educate patients about PrEP and empower them to initiate conversations about PrEP with their providers could be especially instrumental.

Data Availability

Relevant de-identified data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Notes

In the Standard Condition, the discrepancy between the number of patients who met initial screening criteria and the number meeting inclusion criteria for the analytic sample was due to criteria being slightly broader for screening vs. inclusion in the analytic sample as well as a few patients self-reporting characteristics in the survey that differed from clinician-reported patient characteristics on the screening form (e.g., patient identified as gender queer but clinician recorded the patient’s gender identity as woman or female).

References

Harris NS, Johnson AS, Huang YA, et al. Vital signs: status of human immunodeficiency virus testing, viral suppression, and HIV preexposure prophylaxis—United States, 2013–2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(48):1117–23.

Kwakwa HA, Bessias S, Sturgis D, et al. Engaging United States black communities in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: analysis of a PrEP engagement cascade. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(5):480–5.

Huang YA, Weiming Z, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2014–2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(41):1147–50.

Sales JM, Cwiak C, Haddad LB, et al. Brief report: impact of PrEP training for family planning providers on HIV prevention counseling and patient interest in PrEP in Atlanta, Georgia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(4):414–8.

Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):238–43.

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report: diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (Updated). Vol. 31. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published May 2020. Accessed 8 May 2020.

Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23(1):107–15.

Bond KT, Ramos SR. Utilization of an animated electronic health video to increase knowledge of post- and pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV among African American women: nationwide cross-sectional survey. JMIR Form Res. 2019;3(2):e9995.

Chandler R, Hull S, Ross H, Guillaume D, Paul S, Dera N, et al. The pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) consciousness of black college women and the perceived hesitancy of public health institutions to curtail HIV in black women. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1172.

Billings DW, Leaf SL, Spencer J, Crenshaw T, Brockington S, Dalal RS. A randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of a web-based HIV behavioral intervention for high-risk African American women. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(7):1263–74.

Card JJ, Kuhn T, Solomon J, Benner TA, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Translating an effective group-based HIV prevention program to a program delivered primarily by a computer: methods and outcomes. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(2):159–74.

Jones R, Hoover DR, Lacroix LJ. A randomized controlled trial of soap opera videos streamed to smartphones to reduce risk of sexually transmitted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in young urban African American women. Nurs Outlook. 2013;61(4):205-15.e3.

Klein CH, Kuhn T, Altamirano M, Lomonaco C. C-SAFE: a computer-delivered sexual health promotion program for Latinas. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18(4):516–25.

Wingood GM, Card JJ, Er D, et al. Preliminary efficacy of a computer-based HIV intervention for African-American women. Psychol Health. 2011;26(2):223–34.

Amico KR, Balthazar C, Coggia T, Hosek S. Increasing PrEP audio visual representation (PrEP REP) project: development and pilot of a PrEP educational video. International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence. Miami Beach, 2014 [abstract 386].

Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4th ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2013.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 1988.

Brant AR, Dhillon P, Hull S, Coleman M, Ye PP, Lotke PS, et al. Integrating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis into family planning care: a RE-AIM framework evaluation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(6):259–66.

Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, Charles V. Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(2):102–10.

Bond KT, Gunn AJ. Perceived advantages and disadvantages of using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among sexually active Black women: an exploratory study. J Black Sex Relatsh. 2016;3(1):1–24.

Goparaju L, Praschan NC, Warren-Jeanpiere L, Experton LS, Young MA, Kassaye S. Stigma, partners, providers and costs: potential barriers to PrEP uptake among US Women. J AIDS Clin Res. 2017;8(9):730.

Hill LM, Lightfoot AF, Riggins L, Golin CE. Awareness of and attitudes toward pre-exposure prophylaxis among African American women living in low-income neighborhoods in a Southeastern city. AIDS Care. 2021;33(2):239–43.

Hirschhorn LR, Brown RN, Friedman EE, Greene GJ, Bender A, Christeller C, et al. Black cisgender women’s PrEP knowledge, attitudes, preferences, and experience in Chicago. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;84(5):497–507.

Koren DE, Nichols JS, Simoncini GM. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and women: survey of the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs in an urban obstetrics/gynecology clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(12):490–4.

Park CJ, Taylor TN, Gutierrez NR, Zingman BS, Blackstock OJ. Pathways to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among women prescribed PrEP at an urban sexual health clinic. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2019;30(3):321–9.

Pearson T, Chandler R, McCreary LL, Patil CL, McFarlin BL. Perceptions of African American women and health care professionals related to pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2020;49(6):571–80.

Tekeste M, Hull S, Dovidio JF, Safon CB, Blackstock O, Taggart T, et al. Differences in medical mistrust between Black and White women: implications for patient–provider communication about PrEP. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(7):1737–48.

**e L, Wu Y, Meng S, Hou J, Fu R, Zheng H, et al. Risk behavior not associated with self-perception of PrEP candidacy: implications for designing PrEP services. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(10):2784–94.

Zhang C, McMahon J, Fiscella K, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation cascade among health care professionals in the United States: implications from a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(12):507–27.

Calabrese SK, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Integrating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into routine preventive healthcare to avoid exacerbating disparities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1883–9.

Gamarel KE, Golub SA. Intimacy motivations and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adoption intentions among HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in romantic relationships. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(2):177–86.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Planned Parenthood patients who contributed their time and effort by participating in this study. We are grateful to the Planned Parenthood of Southern New England leadership for supporting this study and to the clinical care team members at the two study centers, who provided insightful feedback on the video and were critical to study implementation. We also thank Mr. Emmanuel Ihekweazu for his assistance with medical record data collection. We are grateful to The PrEP-REP Team, led by Dr. K. Rivet Amico, Dr. Sybil Hosek, and Mr. Chris Balthzar, for allowing us to adapt their “What is PrEP?” video for the purposes of the study. We appreciate the funding and resources provided by the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA).

Funding

This study was funded by the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA) Pilot Projects in HIV Program at Yale University. CIRA is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) via Award Number P30-MH062294. Effort was supported by the NIMH via Award Numbers K01-MH103080 (SKC). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH, National Institutes of Health, or Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SKC, SBL, AC, CK, and TSK were involved in the conceptualization and design of the study. SKC, SBL, AC, CK, TSK, JFD, RWG, DFO, and CBS were involved in the acquisition, analysis, and/or interpretation of data. SKC led the writing of the manuscript, with critical review and input from SBL, AC, CK, JFD, RWG, DFO, CBS, MT, TT, DM, BCW, OB, TSK.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SKC received partial support from Gilead Sciences to attend a research conference. All other authors declare no conflicts or competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee (Protocol Number 1603017382) and the George Washington University Committee on Human Research (Protocol Number 180350).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

The authors consent to publication of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Calabrese, S.K., Lane, S.B., Caldwell, A. et al. Electronic Dissemination of a Web-Based Video Promotes PrEP Contemplation and Conversation Among US Women Engaged in Care at Planned Parenthood. AIDS Behav 25, 2483–2500 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03210-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03210-2