Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG) is a routinely performed procedure. However, clinical expertise in laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) is insufficient, and it is only performed at specialized institutions. This study aimed to identify critical factors associated with complications after laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG), particularly LTG.

Methods

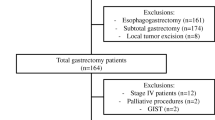

A large-scale database was used to identify critical factors influencing the early outcomes of LTG. Of 1248 patients with resectable gastric cancer who underwent LG, 259 underwent LTG. Predictive risk factors were determined by analyzing relationships between clinical characteristics and postoperative complications. Major complications after LTG were analyzed in detail.

Results

Multivariate analysis of all LG procedures revealed LTG as a risk factor for complications. Morbidity in the LDG and LTG groups was 6.2 % (52 of 835 patients) and 22.4 % (58 of 259 patients), respectively. Major post-LTG complications included anastomotic leakages and pancreatic fistulae. The rate of anastomotic leakage was significantly higher in the LTG group (5.0 %) than in the LDG group (1.2 %); however, it showed a tendency to decrease in more recent cases. Pancreatic fistulae occurred frequently after LTG with D2 lymphadenectomy (LTG-D2), particularly in cases of concomitant pancreatosplenectomy. Obesity was also associated with pancreatic fistula formation after LTG with pancreatosplenectomy.

Conclusions

Compared with LDG, LTG is a develo** procedure. Advances in the surgical techniques associated with the LTG procedure will improve the short-term outcomes of esophagojejunostomy. With regard to LTG-D2, establishing optimal and safe #10 node dissection is one of the most urgent issues. Pancreatic fistula after LTG with pancreatosplenectomy must be investigated in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related death. The mainstay of therapy for advanced gastric cancer is gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy [1]. Standard gastrectomy mainly consists of distal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy.

Laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG) was introduced approximately 20 years ago as a treatment option for gastric cancer [2]. Regarding the early outcome of LDG, randomized controlled trials have revealed the advantages of LDG over open distal gastrectomy: prompt recovery, decreased pain, and short postoperative stay [3–7]. Furthermore, a large-scale cohort study published in 2002 reported low morbidity and mortality rates with LDG [8]. Therefore, LDG is gaining popularity as a surgical treatment for early gastric cancer. Some authors have reported the feasibility of LDG with D2 lymphadenectomy (LDG-D2) for advanced gastric cancer [9–11].

Although open total gastrectomy accounts for approximately 30 % of all open gastrectomies in Japan [12], laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) is performed in less than 10 % of all laparoscopic gastrectomies (LGs), as reported in a large-scale LG study [13]. Consequently, there are only a few clinical reports of analyses of >100 cases of LTG [14].

This may be due to the technical difficulties in performing LTG, such as esophagojejunostomy and concomitant splenectomy. As for splenectomy, in the Japanese treatment guidelines for gastric cancer [1], dissection of the #10 node station at the splenic hilum is essential in LTG with D2 lymphadenectomy (LTG-D2). In Japan, splenectomy is the standard procedure for complete #10 node dissection in open surgery [1]. However, the oncological benefit of concomitant splenectomy remains controversial because of the high morbidity associated with splenectomy [15–19]. Therefore, LTG-D2 is rarely mentioned in clinical reports of LTG.

We have performed 1248 LGs for resectable gastric cancer (including advanced gastric cancer) since 1997 [9, 20–23], and have worked on establishing a standardized LTG procedure [9, 21].

In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed the surgical outcomes of 259 consecutive patients among the abovementioned 1248 patients who underwent LTG.

Methods

Patients

LG with lymphadenectomy was performed for 1248 operable patients with resectable gastric cancer between August 1997 and December 2012 at Fujita Health University Hospital, Japan. Clinical data were recorded in the hospital database consecutively. The clinical database of 1248 patients, of whom 259 underwent LTG, was retrospectively reviewed and analyzed.

Indications for LG and pathological status

Clinical findings were confirmed on the basis of endoscopic study, computed tomography (CT), and fluoroscopy of the upper gastrointestinal series, according to the 13th edition of the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma [24]. Resectability was mainly evaluated by CT examination. If no distant metastases were detected, LG was performed for resectable tumors with any T or any N.

Patients who were diagnosed as T ≥ 2 or N ≥ 1 during preoperative evaluation were scheduled for LG with D2 lymphadenectomy. When direct invasion of other organs (T4) was detected, combined resection was laparoscopically performed to achieve R0 resection, if possible. The classification of pathological status was based on the 13th edition of the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma [24].

Definition of D2 lymphadenectomy

In the present study, D1 (limited) and D2 (extensive) lymphadenectomies were defined according to the 13th edition of the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma [24].

Patients undergoing LTG-D2 for tumors located in the upper stomach were divided into the three groups below on the basis of additional procedures to be performed:

-

(1)

LTG-D2 with splenectomy, which is our standard procedure for advanced gastric cancer in the upper stomach.

-

(2)

LTG-D2 without splenectomy for node-negative advanced gastric cancer located in the lesser curvature of the upper stomach. In LTG-D2 without splenectomy, the adipose tissue with lymph nodes in the splenic hilum and along the distal pancreatic artery was dissected.

-

(3)

LTG-D2 with pancreatosplenectomy for advanced gastric cancer with pancreatic invasion or definite lymph node metastasis at the splenic hilum.

Definition of postoperative complications

The clinical database of LG cases was reviewed to evaluate postoperative complications and other outcomes. Postoperative complications were defined as those occurring within 30 days of surgery, and were graded according to the Clavien–Dindo classification system [25]. Complications classified as ≥ grade IIIa were considered to be positive complications. Postoperative complications were divided into two categories: systemic complications unrelated to the surgical site, such as pneumonia and urinary tract infection, and local complications related to the surgical site, such as anastomotic leakage and pancreatic fistula.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 19.0 J for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To determine predictive factors for postoperative complications, multivariate analysis of all LG cases (n = 1 248) was performed using binary logistic multiple regression. Each factor was divided into 2–6 categories. Predictive factors were as follows: age, gender, body mass index (BMI), comorbidity, prior operation, American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) classification system, preoperative chemotherapy, pathological status, tumor size, lymph node metastasis, resection type, extent of dissection, number of operations, operation duration, and amount of blood loss.

Short-term outcomes, including the number of harvested lymph nodes, duration of operation, amount of blood loss, duration of postoperative stay, and morbidity, mortality, and anastomotic leakage rates were compared according to the type of operation. Morbidity and anastomotic leakage rates were compared between the LDG and LTG groups. In the LTG group, the anastomotic leakage rate was also compared between the first 200 cases and the latter 59 cases.

The short-term outcomes for morbidity and the rate of pancreatic fistula formation were compared across the four LTG types: LTG with D1 lymphadenectomy (LTG-D1), LTG-D2 without splenectomy, LTG-D2 with splenectomy, and LTG-D2 with pancreatosplenectomy. Association between BMI and pancreatic fistula formation among the four LTG groups was evaluated. Multiple comparisons of binomial distribution were estimated using Bonferroni’s correction.

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 65.1 ± 11.3 years and BMI was 22.2 ± 3.2 kg/m2. One or more comorbidities were identified in 674 patients (54.0 %). Prior abdominal surgery was performed in 204 patients. T ≥ 2 cancer was diagnosed as advanced gastric cancer in 431 patients. Numbers of patients for laparoscopic surgical procedures were as follows: LDG, 835; LTG, 259; laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy, 71; laparoscopic pylorus preserved gastrectomy, 42; laparoscopic total residual gastrectomy, 36; and laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy, 5. LG with combined resection of other organs to achieve R0 resection or to treat synchronous multiple primary tumors was performed in 148 patients.

Risk factors for postoperative complications

The overall morbidity and mortality rates were 10.3 and 0.3 %, respectively. According to multivariate analyses, LTG (odds ratio (OR) 4.331; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 2.790–6.722; P < 0.001) and laparoscopic total residual gastrectomy (OR 5.344; 95 % CI 2.241–12.739; P < 0.001) were independent risk factors associated with postoperative complications (Table 2). The morbidity rate was higher and postoperative stay was longer in the LTG group than in the LDG group. Blood loss—a risk factor for postoperative complications—in the LTG group was also higher than that in the LDG group (Table 3). The frequency of postoperative complications, particularly local complications, was higher after LTG than after LDG (Fig. 1). A majority of these local complications after LTG involved pancreatic fistula and anastomotic leakage (Fig. 2).

Anastomotic leakage

The anastomotic leakage rate was significantly higher after LTG than after LDG (Fig. 3). The overall leakage rate for LDG cases (n = 835) was 1.2 %. This included 329 gastroduodenostomies and 506 gastrojejunostomies, with leakage rates of 2.4 and 0.4 %, respectively. Esophagojejunostomy was performed in all patients undergoing LTG. Although not significantly different (P = 0.183), the anastomotic leakage rate among the latter 59 LTG patients was 1.7 %; this was lower than that (6.0 %) for the first 200 LTG patients. Among all cases of laparoscopic gastrectomy (n = 1248), the anastomotic leakage rates of patients with and without preoperative chemotherapy were 2.9 % (5/173) and 2.9 % (31/1075), respectively. The same rates in LTG (n = 259) were 4.4 % (3/68) and 5.2 % (10/191), respectively. There was no significant difference in anastomotic leakage rates between patients with and without preoperative chemotherapy in both laparoscopic gastrectomy (P = 0.996) and LTG (P = 0.789).

Pancreatic fistula

The rate of pancreatic fistula formation was higher after LTG-D2 than after LDG-D1, LDG-D2, or LTG-D1 (P < 0.001, Fig. 4). With regard to combined resection in the LTG-D2 groups, morbidity and the rate of pancreatic fistula formation were higher in LTG-D2 with pancreatosplenectomy than in the other two groups (P < 0.001, Fig. 5). After LTG-D2 with pancreatosplenectomy, it was found that BMI was significantly higher in patients who developed a pancreatic fistula than in those who did not (P = 0.011, Table 4).

Discussion

The low invasiveness of LG is expected to facilitate the prompt recovery of patients and shorten hospital stays. However, when a serious postoperative complication happens, it seems to negate this beneficial feature and may introduce fatal complications. Therefore, analysis and prevention of postoperative complications is crucial to maximizing the efficacy of LG. From this point of view, we focused on postoperative complications classified as grade IIIa or higher in the Clavien–Dindo classification [25] in subsequent analyses. This was because most major postoperative complications, i.e., those classified grade IIIa or higher, cause prolonged postoperative hospital stays. On the other hand, the complications of LG classified as grade II could be conservatively treated by medications within a week, and did not cause evident prolongation of hospital stay or surgery-related death.

Using multivariate analysis, LTG was identified as a risk factor for postoperative complications. In particular, the rate of local complications after LTG was significantly higher than that after LDG. A Korean study [13] previously identified LTG as a risk factor for local complications. Compared with LDG, LTG requires more technical procedures such as esophagojejunostomy and node dissection in the splenic hilum. In order to clarify the relationship between LTG-specific surgical procedures and local complications, we extensively analyzed 259 patients who underwent LTG.

The anastomotic leakage rate after LTG was higher than that after LDG. By performing multivariate analyses, preoperative chemotherapy was also identified as one of the independent risk factors for postoperative complications, but the correlation between preoperative chemotherapy and anastomotic leakage was not observed in either all cases of laparoscopic gastrectomy or in only the LTG cases. Further clinical trials should be conducted to clarify the influence of preoperative chemotherapy on complications after laparoscopic surgery for gastric cancer. While develo** a novel intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy procedure for reconstruction [21], we observed anastomotic leakage in some early cases. Tension and blood supply at the anastomotic site are closely related to leakage. In LTG, laparoscopic preparation of the jejunal mesentery for esophagojejunostomy is an essential procedure that is not performed during LDG. Our standard procedure after LTG is intracorporeal Roux-en-Y reconstruction. In this procedure, side-to-side esophagojejunostomy is performed using a linear stapler. Intracorporeal preparation of the jejunum for esophagojejunostomy can cause disturbance of the blood supply to the jejunum around the anastomotic site due to the cutting of the marginal arteries. Furthermore, jejunal mobilization is often difficult when the mesentery of the jejunum is shortened by obesity or adhesion. In such cases, tension at the anastomosis may cause leakage. Leakage occurred most commonly at the most cranial site of the stapling line, where the tension was the strongest.

The higher leakage rate after LTG compared with that after LDG can be attributed to these multiple factors. Recently, we endeavored to pay great attention to preserving the blood supply to the jejunal limb and to alleviate strain at the site of anastomosis through adequate intracorporeal mobilization of the jejunum. Consequently, the anastomotic leakage rate tended to decline after 200 cases of LTG. These results suggest that improving the skills of the surgeons of our institution in intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy and jejunum mobilization procedures can alleviate leakage rates after LTG. In general, the LDG learning curve is regarded as approximately 50–100 cases; furthermore, surgeons who experienced >50 cases of LDG were defined as “experts” in this study. However, a substantial number of clinical cases were required for the development and standardization of the novel LTG anastomotic procedure because esophagojejunostomy of LTG is not experienced during the LDG procedure. Consequently, our institution required 200 cases of LTG to alleviate the anastomotic leakage rate. The individual learning curve for the LTG procedure should be investigated in future.

The Japanese treatment guidelines for gastric cancer [1] recommend lymphadenectomy of the splenic hilar nodes (#10 node station) for D2 node dissection in patients undergoing LTG. To perform a safe and oncologically optimal surgical procedure, we adopted three distinct LTG-D2 procedures for advanced gastric cancer located in the upper stomach, depending on the tumor location and extent and the nodal status. We adopted LTG-D2 without splenectomy (the least invasive procedure) for tumors with a low risk of nodal metastasis in the splenic hilum [26]. Consequently, we found that the rate of pancreatic fistula formation after LTG-D2 without splenectomy was the lowest among the three groups. Spleen-preserved D2 dissection can be a safe and effective means for prophylactic D2 lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing LTG.

An evaluation of long-term outcome is, however, required to standardize LTG-D2 without splenectomy as a treatment for advanced gastric cancer. Although a high morbidity rate after open total gastrectomy with splenectomy has been reported [15–19], LTG-D2 with splenectomy has shown a relatively low morbidity rate compared with open gastrectomy. Therefore, randomized studies are required to determine the superiority of LTG-D2 with splenectomy as compared to open total gastrectomy with splenectomy.

The rate of pancreatic fistula formation was significantly higher after LTG-D2 with pancreatosplenectomy than after other surgical procedures. This shows that pancreatosplenectomy for the therapeutic dissection of lymph nodes #11d and #10 is a critical influence on the rate of pancreatic fistula formation after LTG. In particular, the mean BMI of patients with pancreatic fistula was significantly higher than that of those without. In this study, the pancreas was transected by a linear stapler for pancreatosplenectomy. In this procedure, thick pancreatic parenchyma and surrounding adipose tissue may disrupt the stapled line of the pancreas, leading to the formation of a pancreatic fistula; thus, extra attention is required for obese patients undergoing LTG-D2 with pancreatosplenectomy. To prevent the disruption of the stapler line after transection of the thick pancreas, we initiated pre-compression for 5 min using intestinal clamp forceps. Then we transected the pancreas slowly using a linear stapler with three stapler lines of extra-thick range.

This study has some limitations. First, it was a retrospective review of clinical data. Second, the sample size of LTG cases (n = 259) was small to arrive at any definitive conclusions. A large-scale prospective clinical study is required to evaluate the efficacy of LTG in the future.

In conclusion, LTG is still a develo** procedure compared with LDG. Critical factors that influence the early outcomes of LTG are anastomotic procedure and combined resection of the pancreas. Technical improvements can contribute to improve the short-term outcomes of esophagojejunostomy. An investigation of the optimal procedure for #10 lymph node dissection and an assessment of the oncological results of these procedures are urgently needed to establish D2 lymphadenectomy of LTG. Pancreatic fistula formation after LTG with pancreatosplenectomy is a problem that must be overcome. Clinical trials are required to establish safe and beneficial LTG procedures in the future.

References

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–23.

Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Suqimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146–8.

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Fujii K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y. A randomized controlled trial comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for the treatment of early gastric cancer: an interim report. Surgery. 2002;131:306–11.

Lee JH, Han HS, Lee JH. A prospective randomized study comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer: early results. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:168–73.

Hayashi H, Ochiai T, Shimada H, Gunji Y. Prospective randomized study of open versus laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with extraperigastric lymph node dissection for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1172–6.

Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, et al. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:721–7.

Kim HH, Hyung WJ, Cho GS, Kim MC, Han SU, Kim W, et al. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an interim report—a phase III multicenter, prospective, randomized trial (KLASS Trial). Ann Surg. 2010;251:417–20.

Kim W, Song KY, Lee HJ, Han SU, Hyung WJ, Cho GS. The impact of comorbidity on surgical outcomes in laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;248:793–9.

Uyama I, Sugioka A, Fujita J, Komori Y, Matsui H, Hasumi A. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with distal pancreatosplenectomy and D2 lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 1999;2:230–4.

Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, et al. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232–7.

Cai J, Wei D, Gao CF, Zhang CS, Zhang H, Zhao T. A prospective randomized study comparing open versus laparoscopy-assisted D2 radical gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer. Dig Surg. 2011;28:331–7.

Isobe Y, Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Oda I, Hayashi K, Miyashiro I, et al. Gastric cancer treatment in Japan: 2008 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:301–16.

Kim MC, Kim W, Kim HH, Ryu SW, Ryu SY, Song KY, et al. Risk factors associated with complications following laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a large-scale Korean multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2692–700.

Jeong GA, Cho GS, Kim HH, Lee HJ, Ryu SW, Song KY. Laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Surgery. 2009;146:469–74.

Katai H, Yoshimura K, Fukagawa T, Sano T, Sasako M. Risk factors for pancreas-related abscess after total gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:137–41.

Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, Kurokawa Y, Nashimoto A, Kurita A, et al. D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para-aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:453–62.

Gong DJ, Miao CF, Bao Q, Jianq M, Zhanq LF, Tong XT, et al. Risk factors for operative morbidity and mortality in gastric cancer patients undergoing total gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6560–3.

Oh SJ, Hyung WJ, Li C, Song J, Kang W, Rha SY, et al. The effect of spleen-preserving lymphadenectomy on surgical outcomes of locally advanced proximal gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:275–80.

Sakuramoto S, Kikuchi S, Futawatari N, Katada N, Moriya H, Hirai K, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted pancreas- and spleen-preserving total gastrectomy for gastric cancer as compared with open total gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2416–23.

Shinohara T, Kanaya S, Taniguchi K, Fujita T, Yanaga K, Uyama I. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1138–42.

Inaba K, Satoh S, Ishida Y, Taniguchi K, Isogaki J, Kanaya S, et al. Overlap method: novel intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:25–9.

Shinohara T, Satoh S, Kanaya S, Ishida Y, Taniguchi K, Isogaki J, et al. Laparoscopic versus open D2 gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:286–94.

Nagasako Y, Satoh S, Isogaki J, Inaba K, Taniguchi K, Uyama I. Impact of anastomotic complications on outcome after laparoscopic gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:849–54.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 2nd English ed. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24.

Dindo D, Dermartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications. a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 63336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

Sano T, Yamamoto S, Sasako M. Randomized controlled trial to evaluate splenectomy in total gastrectomy for proximal gastric carcinoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG 0110-MF. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002;32:363–4.

Acknowledgments

This work was not supported by any grants or funding. No author has any commercial association or financial involvement that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kawamura, Y., Satoh, S., Suda, K. et al. Critical factors that influence the early outcome of laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer 18, 662–668 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0392-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0392-9