Abstract

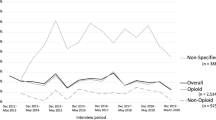

The ongoing opioid epidemic has been a global concern for years, increasingly due to its heavy toll on young people’s lives and prospects. Few studies have investigated trends in use of the wider range of drugs prescribed to alleviate pain, psychological distress and insomnia in children, adolescents and young adults. Our aim was to study dispensation as a proxy for use of prescription analgesics, anxiolytics and hypnotics across age groups (0–29 years) and sex over the last 15 years in a large, representative general population. The study used data from a nationwide prescription database, which included information on all drugs dispensed from any pharmacy in Norway from 2004 through 2019. Age-specific trends revealed that the prevalence of use among children and adolescents up to age 14 was consistently low, with the exception of a substantial increase in use of melatonin from age 5. From age 15–29, adolescents and young adults used more prescription drugs with increasing age at all time points, especially analgesics and drugs with higher potential for misuse. Time trends also revealed that children from age 5 were increasingly dispensed melatonin over time, while adolescents from age 15 were increasingly dispensed analgesics, including opioids, gabapentinoids and paracetamol. In contrast, use of benzodiazepines and z-hypnotics slightly declined in young adults over time. Although trends were similar for both sexes, females used more prescription drugs than their male peers overall. The upsurge in use of prescription analgesics, anxiolytics and hypnotics among young people is alarming.

Trial registration The study is part of the overarching Killing Pain project. The rationale behind the Killing Pain research was pre-registered through ClinicalTrials.gov on April 7, 2020. Registration number NCT04336605; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT04336605.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Increasing use of prescription drugs for pain, psychological distress and insomnia among young people is a growing global concern [35]. While pharmacological treatment can provide effective short-term symptom relief, such as in acute and palliative care, potential misuse involves risk in terms of negative health consequences. For clinicians working with young patient populations, there is a fine line between undertreating these often co-occurring conditions and limiting potential misuse. However, despite these concerns the scope and trends of use for the wider range of prescription analgesics, anxiolytics and hypnotics have rarely been studied systematically, especially across the entire developmental trajectory and over extended time periods.

Prescription drugs with higher potential for misuse, such as opioids, gabapentinoids, benzodiazepines and z-hypnotics, are generally not recommended for children and adolescents unless they have a clear indication for treatment, which makes adequate systematic surveillance critical [47]. Potential misuse can lead to dependence, reduced efficacy and increased risk of acute and long-term morbidity and mortality [8, 21, 51]. Importantly, symptoms of cognitive impairment and sedation may also negatively impact social participation and school performance [2].

Recently, the long-term effects of alternative drugs with lower misuse potential have also been questioned. Although safer in terms of potential for misuse, frequent use of analgesics, such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), has been linked to increased risk of medication-overuse headache, cardiovascular risk, gastrointestinal bleeding and renal failure [12, 13, 30]. Furthermore, the consequences of prolonged use of sleep aids, such as melatonin and alimemazine, have not yet been systematically reviewed in children and adolescents [10, 23, 43]. The increase in overweight and sedentary lifestyles may also contribute to increased risk of headaches and musculoskeletal pain [1, 7, 52]. Additionally, some evidence indicates that adolescents and young adults are under more stress when it comes to academic performance and that social media use exacerbate symptoms of depression and anxiety [14, 26]. These types of symptoms are currently also worsening among children and adolescents as a consequence of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which supports the need to take their health complaints seriously [38]. Prescription drugs are in addition viewed as safer, easy to access and associated with less societal stigma compared to illicit drugs among adolescents and young adults who misuse [16]. Second, another potential explanation is that it has become more common to prescribe prescription drugs for health complaints to this group.

Strengths and limitations

The study included the whole Norwegian population and all dispensed drugs from pharmacies across the country. It investigated the entire developmental trajectory, from childhood through to young adulthood, over 15 years. Moreover, it included a wide range of prescription drugs used to treat pain, psychological distress and insomnia. The study also had several limitations. It did not include drugs prescribed through hospitals or institutional settings, nor use of over-the-counter drugs, such as paracetamol, NSAIDs, and (more recently) melatonin, which are readily available without a prescription. Information about why the drugs were prescribed was not available and since the study only included cross-sectional measurements, it was not possible to study individual use over time. Formal statistical tests for time differences were also not feasible since the groups of individuals that were included in consecutive calendar years were not completely independent. It should also be noted that while it is realistic to assume the dispensed drugs were consumed by the recipients, there may have been cases where they were not. Finally, the inferences that can be made from the DDD calculations are limited as DDDs have primarily been developed for adults and are therefore likely less accurate for the actual use in children and young people. DDDs for different products within the same drug group (e.g., opioids) may also vary to some extent and are thus primarily informative for comparisons of overall use of the different drug groups over time [33].

Conclusion and future directions

Young people from the age of 15 are more likely to use prescription analgesics and drugs with higher potential for misuse with increasing age. This age-specific trend has been consistent over the past 15 years, while use of analgesics has steadily been increasing in this age group over time. During the same time period, use of melatonin for insomnia has also become increasingly common in children from age 5. These trends call for public health interventions and a proactive approach across research and clinical practice to better understand the etiological mechanisms driving the increase in prescription drug use.

References

Alzahrani H, Mackey M, Stamatakis E, Zadro JR, Shirley D (2019) The association between physical activity and low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep 9:1–10

Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Freedman-Doan P, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Messersmith EE (2008) The education-drug use connection: How successes and failures in school relate to adolescent smoking, drinking, drug use, and delinquency. Psychology Press, London

Bell J, Paget SP, Nielsen TC, Buckley NA, Collins J, Pearson S-A, Nassar N (2019) Prescription opioid dispensing in Australian children and adolescents: a national population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 3:881–888

Besag FM, Vasey MJ, Lao KS, Wong IC (2019) Adverse events associated with melatonin for the treatment of primary or secondary sleep disorders: a systematic review. CNS Drugs 33:1167–1186

Blaker H (2000) Confidence curves and improved exact confidence intervals for discrete distributions. Can J Stat 28:783–798

Cancer Registry of Norway (2021) Nasjonalt kvalitetsregister for barnekreft, Årsrapport 2020. [National quality registry for childhood cancer, Report for 2020]. Cancer Registry of Norway, Oslo

Chai NC, Scher AI, Moghekar A, Bond DS, Peterlin BL (2014) Obesity and headache: part I—a systematic review of the epidemiology of obesity and headache. Headache J Head Face Pain 54:219–234

Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Deyo RA (2015) The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med 162:276–286

Costello R, McDonagh J, Hyrich KL, Humphreys JH (2022) Incidence and prevalence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the United Kingdom, 2000–2018: results from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Rheumatology 61:2548–2554

De Bruyne P, Christiaens T, Boussery K, Mehuys E, Van Winckel M (2017) Are antihistamines effective in children? A review of the evidence. Arch Dis Child 102:56–60

de Zambotti M, Goldstone A, Colrain IM, Baker FC (2018) Insomnia disorder in adolescence: diagnosis, impact, and treatment. Sleep Med Rev 39:12–24

Diener H-C, Holle D, Solbach K, Gaul C (2016) Medication-overuse headache: risk factors, pathophysiology and management. Nat Rev Neurol 12:575–583

Eccleston C, Cooper TE, Fisher E, Anderson B, Wilkinson NM (2017) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8(8):CD012537. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012537.pub2

Eriksen IM (2021) Class, parenting and academic stress in Norway: middle-class youth on parental pressure and mental health. Discourse Stud Cult Polit Educ 42:602–614

European Medicines Agency (2021) Circadin. In: EMA

Fleary SA, Heffer RW, McKyer ELJ (2013) Understanding nonprescription and prescription drug misuse in late adolescence/young adulthood. J Addict 2013:709207

Fredheim OM, Skurtveit S, Loge JH, Sjøgren P, Handal M, Hjellvik V (2020) Prescription of analgesics to long-term survivors of cancer in early adulthood, adolescence, and childhood in Norway: a national cohort study. Pain 161:1083–1091

Freo U, Ruocco C, Valerio A, Scagnol I, Nisoli E (2021) Paracetamol: a review of guideline recommendations. J Clin Med 10:3420

Furu K (2009) Establishment of the nationwide Norwegian Prescription Database (NorPD)—new opportunities for research in pharmacoepidemiology in Norway. Norsk Epidemiologi 18

Hartz I, Skurtveit S, Steffenak AK, Karlstad Ø, Handal M (2016) Psychotropic drug use among 0–17 year olds during 2004–2014: a nationwide prescription database study. BMC Psychiatry 16:12

Horowitz MA, Kelleher M, Taylor D (2021) Should gabapentinoids be prescribed long-term for anxiety and other mental health conditions? Elsevier, Amsterdam

Hudgins JD, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Bourgeois FT (2019) Prescription opioid use and misuse among adolescents and young adults in the United States: a national survey study. PLoS Med 16:e1002922

Haack M, Simpson N, Sethna N, Kaur S, Mullington J (2020) Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacology 45:205–216

Jonassen R, Hilland E, Harmer CJ, Abebe DS, Bergem AK, Skarstein S (2021) Over-the-counter analgesics use is associated with pain and psychological distress among adolescents: a mixed effects approach in cross-sectional survey data from Norway. BMC Public Health 21:1–12

Kaguelidou F, Durrieu G, Clavenna A (2019) Pharmacoepidemiological research for the development and evaluation of drugs in pediatrics. Therapies 74:315–324

Keles B, McCrae N, Grealish A (2020) A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int J Adolesc Youth 25:79–93

King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, MacDonald AJ (2011) The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain 152:2729–2738

Krause KR, Chung S, Adewuya AO, Albano AM, Babins-Wagner R, Birkinshaw L, Brann P, Creswell C, Delaney K, Falissard B (2021) International consensus on a standard set of outcome measures for child and youth anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Lancet Psychiatry 8:76–86

Langan SM, Schmidt SA, Wing K, Ehrenstein V, Nicholls SG, Filion KB, Klungel O, Petersen I, Sorensen HT, Dixon WG, Guttmann A, Harron K, Hemkens LG, Moher D, Schneeweiss S, Smeeth L, Sturkenboom M, von Elm E, Wang SV, Benchimol EI (2018) The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE). Bmj 363:k3532

McCrae J, Morrison E, MacIntyre I, Dear J, Webb D (2018) Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol–a review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 84:2218–2230

Mogil JS (2020) Qualitative sex differences in pain processing: emerging evidence of a biased literature. Nat Rev Neurosci 21:353–365

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2011) Management of generalised anxiety disorder in adults. NICE, London

Nielsen S, Gisev N, Bruno R, Hall W, Cohen M, Larance B, Campbell G, Shanahan M, Blyth F, Lintzeris N (2017) Defined daily doses (DDD) do not accurately reflect opioid doses used in contemporary chronic pain treatment. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 26:587–591

Ohm E, Madsen C, Alver K (2017) Injuries in Norway. Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), Oslo

Perlmutter AS, Bauman M, Mantha S, Segura LE, Ghandour L, Martins SS (2018) Nonmedical prescription drug use among adolescents: global epidemiological evidence for prevention, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Addict Rep 5:120–127

Pielech M, Lunde CE, Becker SJ, Vowles KE, Sieberg CB (2020) Comorbid chronic pain and opioid misuse in youth: knowns, unknowns, and implications for behavioral treatment. Am Psychol 75:811

Qato DM, Alexander GC, Guadamuz JS, Lindau ST (2018) Prescription medication use among children and adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics 142

Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S (2021) Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 175:1142–1150

Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, Bjorvatn B, Dolenc Groselj L, Ellis JG, Espie CA, Garcia-Borreguero D, Gjerstad M, Gonçalves M (2017) European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res 26:675–700

Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ (2019) Sex differences and the neurobiology of affective disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 44:111–128

Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CH (2022) Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol 61:287–305

Sidorchuk A, Isomura K, Molero Y, Hellner C, Lichtenstein P, Chang Z, Franck J, Fernández de la Cruz L, Mataix-Cols D (2018) Benzodiazepine prescribing for children, adolescents, and young adults from 2006 through 2013: a total population register-linkage study. PLoS Med 15:e1002635

Sivertsen B, Vedaa Ø, Harvey AG, Glozier N, Pallesen S, Aarø LE, Lønning KJ, Hysing M (2019) Sleep patterns and insomnia in young adults: a national survey of Norwegian university students. J Sleep Res 28:e12790

Sommerschild HT, Berg CL, Blix HS, Dansie LS, Litleskare I, Olsen K, Sharikabad MN, Amberger M, Torheim S, Granum T (2021) Legemiddelforbruket i Norge 2016–2020—Data fra Grossistbasert legemiddelstatistikk og Reseptregisteret. [Drug Consumption in Norway 2016–2020—data from Norwegian Drug Wholesales Statistics and the Norwegian Prescription Database, 2016–2020]. Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), Oslo

Steliarova-Foucher E, Colombet M, Ries LA, Moreno F, Dolya A, Bray F, Hesseling P, Shin HY, Stiller CA, Bouzbid S (2017) International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001–10: a population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol 18:719–731

Suh S, Cho N, Zhang J (2018) Sex differences in insomnia: from epidemiology and etiology to intervention. Curr Psychiatry Rep 20:1–12

The Norwegian Directorate of Health (2015) Nasjonal faglig veileder om vanedannende legemidler—rekvirering og forsvarlighet. The Norwegian Directorate of Health, Oslo

The Norwegian Pharmaceutical Product Compendium (Felleskatalogen AS) ATC-register. [ATC-registry]. Felleskatalogen AS, Oslo

Torrance N, Veluchamy A, Zhou Y, Fletcher EH, Moir E, Hebert HL, Donnan PT, Watson J, Colvin LA, Smith BH (2020) Trends in gabapentinoid prescribing, co-prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines, and associated deaths in Scotland. Br J Anaesth 125:159–167

Tähkäpää S-M, Saastamoinen L, Airaksinen M, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Aalto-Setälä T, Kurko T (2018) Decreasing trend in the use and long-term use of benzodiazepines among young adults. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 28:279–284

Umbricht A, Velez ML (2021) Benzodiazepine and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (Z-drugs): the other epidemic. Textbook of addiction treatment. Springer, Berlin, pp 141–156

Walsh TP, Arnold JB, Evans AM, Yaxley A, Damarell RA, Shanahan EM (2018) The association between body fat and musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 19:1–13

Wei S, Smits MG, Tang X, Kuang L, Meng H, Ni S, **ao M, Zhou X (2020) Efficacy and safety of melatonin for sleep onset insomnia in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med 68:1–8

Wesselhoeft R, Rasmussen L, Jensen PB, Jennum PJ, Skurtveit S, Hartz I, Reutfors J, Damkier P, Bliddal M, Pottegård A (2021) Use of hypnotic drugs among children, adolescents, and young adults in Scandinavia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 144:100–112

Williams LA, Richardson M, Marcotte EL, Poynter JN, Spector LG (2019) Sex ratio among childhood cancers by single year of age. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66:e27620

World Health Organization (2021) ATC/DDD toolkit. In: WHO

World Health Organization (2021) Defined daily dose (DDD). In: WHO

World Health Organization (2020) Guidelines on the management of chronic pain in children. In: WHO

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), the Division of Clinical Neuroscience at Oslo University Hospital, the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies, the Change Factory and the Norwegian Council for Mental Health, for their collaboration. The Killing Pain project has been funded by the Dam Foundation (project number 2020/FO283043) and the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies (NKVTS). SOS and MH, both from NIPH, were funded in part by the Norwegian Research Council (Grant number 320360).

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study has been approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC), (reference 2017/2229).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stangeland, H., Handal, M., Skurtveit, S.O. et al. Killing pain?: a population-based registry study of the use of prescription analgesics, anxiolytics, and hypnotics among all children, adolescents and young adults in Norway from 2004 to 2019. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32, 2259–2270 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02066-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02066-8