Abstract

Summary

We analyzed 12-month compliance for all ten oral osteoporosis drugs in the Netherlands by medication possession ratio (MPR ≥ 80%) in 105,506 patients, and persistence in 8,626 starters indicated high MPR (91%), low persistence (43%), and no restart in 78% of the stoppers after 18 months.

Introduction

We studied compliance and persistence for all available oral osteoporosis medications on a national scale in the Netherlands.

Methods

We analyzed the IMS Health’s longitudinal prescription database, which represents 73% of all pharmacies in the Netherlands. Twelve-month compliance was measured by medication possession ratio (MPR) in a cross-sectional cohort of 105,506 patients who received at least three prescriptions. Twelve-month persistence (no gap in refills for >6 months) was measured in all 8,626 consecutive patients starting therapy, with a further follow-up in non-persistent patients during an additional 18 months for evaluation of switching, restart, or definitive stop** oral medication. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of characteristics of non-persistence.

Results

MPR of ≥80% was found in 91% of patients. Persistence was 43% (range, 29–52%). Persistence was related to age >60 years (ORs, 1.41 to 1.64), pharmacy outside very dense urban area (ORs, 1.39 to 1.44), additional use of calcium and/or vitamin D supplementation (OR, 1.26 and CI, 1.13, 1.39) and use of glucocorticoids (OR, 0.65 and CI, 0.59, 0.72) or cardiovascular medication (OR, 0.88 and CI, 0.79, 0.97). Of non-persistent patients, 22% restarted within 18 months with oral osteoporosis drugs.

Conclusions

One-year compliance for all available oral osteoporosis medications was high, but 1-year persistence was low. Most stoppers did not restart or switch during an additional 18-month follow-up. These data indicate a major failure to adequately treat patients at high risk for fractures in daily practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

After the age of 50 years, more than one in two women and one in five men will suffer a fracture during their remaining lifetime [1, 2]. Fractures result in high economic costs, morbidity, disability, mortality, and subsequent fractures, which are highest immediately after fracture, but remain increased during long-term follow-up [3-7]. It is estimated that 20% to 50% of fractures related to osteoporosis can be prevented by specific osteoporosis drug treatment as reported in randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs). However, there is a large discrepancy between the relative high adherence to osteoporosis medication in RCTs (e.g., in the Fracture Intervention Trial in postmenopausal women with increased fracture risk, compliance of >74% was found in 96% of the participants [8]), and the poor adherence in daily clinical practice [9, 10]. The main components of adherence are compliance (how correctly, in terms of dose and frequency, a patient takes the available medication) and persistence (how long a patient receives therapy after initiating treatment), but these definitions vary among publications [11].

We used the following definitions. Compliance was defined as the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen, and persistence as the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy and adherence as a general term encompassing both persistence and compliance [12]. Compliance and persistence for medications used in chronic diseases are notoriously poor, and osteoporosis is no exception. About 50% of patients fail to comply or persist with osteoporosis treatment within 1 year [13, 14]. Most importantly, low compliance and persistence result in a significantly lower anti-fracture effect, as has been shown for bisphosphonates [9, 13-24]. Although cut-off points are arbitrary and could lead to loss of information, a medication possession ratio (MPR) of 80% or greater is commonly regarded as the lowest threshold for optimal efficacy in the prevention of fractures [14, 19].

Little is known about the extent to which patients after discontinuing treatment in the routine care restart or switch to other drugs in the same class. In one retrospective study, it was found that of the patients who stopped therapy for at least 6 months, an estimated 30% restarted treatment within 6 months, and 50% restarted within 2 years [25]. Factors that are related to low compliance and/or persistence in daily practice are difficult to identify [13]. Insofar they have been studied, they include characteristics related to the drug (such as adverse events, cost, and dosing), to the patient (such as education, information, co-morbidity, and co-medication), and to the doctor (such as follow-up strategies and adherence to osteoporosis guidelines) [20, 26, 27].

In a retrospective, longitudinal, large prescription database covering more than 70% of the Dutch population, we studied adherence in terms of 12-month compliance and persistence, characteristics of non-persistent patients (gender, age, living area, co-morbidity, co-medication, and prescriber) and analyzed during 18 months after stop** the extent of restart or switch to other osteoporosis medication in non-persistent patients.

Methods

Data source

The study was carried out in the routine practice setting in the Netherlands. Data were obtained from the IMS Health’s longitudinal prescription database (LRx, affiliate Capelle ad Ijssel, Netherlands). This source consists of anonymized patient longitudinal prescription records from a representative sample of pharmacies and dispensing general practitioners (GPs) with a coverage of 73% of the retail dispensing corresponding to the drug consumption of 11.9 million of the 16.5 million Dutch inhabitants. In the Netherlands, ambulant patients visiting a specialist also receive their medication via the retail channel, and so this dispensing is also covered by the database. The computerized drug-dispensing histories contain complete data concerning the dispensed drug, type of prescriber, dispensing date, dispensed amount, prescribed dose regimen, and the prescription length. Data for each patient were anonymized in each pharmacy independently without linkage of the dispensed prescriptions to the same unique patient across pharmacies.

Patients in Netherlands are usually loyal to one pharmacy [28]. Because moving to other home (e.g., nursing home) or dying could bias the persistence, we performed an additional persistence analysis and compared persistence of osteoporosis medication in patients who did and did not refill other medications.

All oral drugs which are prescribed for osteoporosis in the Netherlands were evaluated (Table 1). No distinction between alendronate 10 and 70 mg branded or generic could be made because pharmacies are free to dispense the variant they prefer irrespective of the doctors prescribing, but Fosavance ® could be identified. Compliance and persistence for calcium and vitamin D supplements were not analyzed.

Analysis of adherence included two distinct, albeit overlap**, components; compliance (in a cohort of non-switching and persistent patients), and persistence (in a cohort of patients who started osteoporosis medication) and was further evaluated in non-persistent patients for subsequent switch or definite non-persistence.

Compliance

Compliance was expressed as the medication possession ratio (MPR), calculated by dividing the supply of drugs in treatment days by the interval time between first and last date of dispensing [29, 30]. Over a period of 1 year (November 2007–October 2008), all patients who started or who were already previously on osteoporosis medication and who did not switch between the studied osteoporosis drugs and had at least three prescriptions were selected. This last restriction was chosen for reasons of reducing individual variability of dispensing rate. As a rule in the Netherlands, one prescription covers maximally 90 days. In this analysis, we started with 153,903 patients and ended with 105,506 patients. A total of 12,263 patients were lost because of drug switching and 36,134, because they received less than three prescriptions.

Persistence

The 1-year rates of persistence with treatment were defined as the percentage of patients who used the drug for at least 365 days without failure to receive a refill and without switching to another oral osteoporosis drug. Such evaluation of persistence provides insight into the duration of treatment supply [11, 30, 31]. The treatment episode was defined as the period of time in which the patient continuously used the specific drug. If the gap between consecutive dispensing dates was more than 6 months, the last prescription of the drug before this gap was considered as the last prescription. The treatment period lasts from start date till end date of this last prescription using the therapy duration of this last prescription as recorded by the pharmacy. Each patient was judged during 365 days as being either persistent (still on medication on drug of start) or non-persistent (no longer using this drug of start). Persistence after 1 year was calculated and used to correlate with factors that could influence 1-year persistence. Patients who stopped the initial drug during the first half year were followed during an additional 18 months.

For the analysis of 12 months’ persistence, data were obtained from the LRx database between September 2006 and October 2008. All consecutive patients starting one of the available oral osteoporosis drugs between March and May 2007 and not receiving prescriptions of that particular drug during at least 6 months previous to the start were included. This timing selection allowed in all patients to include a 6-month follow-up (trailing) period and a 6-month lookback period (Fig. 1).

In this analysis, we started with a total of 171,293 patients having any osteoporosis medication of which 168,749 received oral medication. Most patients (n = 99,148) received their first prescription in our prescription database in the lookback period or during reporting and trailing period (n = 60,975), which results in 8,626 starters for the analysis of persistence. Moving to another address (e.g., nursing home) or death during follow-up could have biased the persistence results. Therefore, persistence was also separately analyzed in patients who also continued other than osteoporosis medications at the end of the period.

Determinants of persistence

In order to explore factors that could be related to 12-month persistence, three groups of possible determinants were recorded. First, we used the patient-depending information like age, gender, sex, and rurality of the patients’ pharmacy. Second, we studied the co-medications at start and in the trailing period. Third, we added the specialty of the prescriber who prescribed the first osteoporosis drug. Co-medications were analyzed for ten treatment segments, each corresponding with one or more therapeutic areas. Some treatment classes had a relation to osteoporosis (e.g., calcium, vitamin D, and glucocorticosteroids) and others were chronic medication classes for other diseases (e.g., cardiovascular diseases)

Follow-up of stoppers

Patients who stopped with the drug of start due to lack of renewal prescriptions for any oral osteoporosis drug were selected. As illustrated in Fig. 1, these patients are tracked for 18 months of which the first 6 months, the trailing period, serve to measure their stop** on the medication. The follow-up of these patients is observed during the connecting period of 12 months in which a new prescription for any oral osteoporosis drug is reported. We observed in our prescription database 38,349 patients receiving a prescription for an oral osteoporosis drug per month, of which 35,207 were receiving osteoporosis medication during the following 6 months. We choose to include these stoppers for 3 months, resulting in a total group of 9,372 stoppers.

Statistical analysis

Determinants of persistence were analyzed by logistic multivariate regression model with adjusted odds ratios (or with 95% confidence interval) using SAS version 9.1. Statistical significance for the model was defined at an alpha level of 0.05. The independent covariates were included by a forward stepwise selection technique with an entry probability of 0.05. The Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test was used to assess the reliability of the model [32]. For the significance testing of differences in the MPR, a univariate logistic regression model was used.

Results

Compliance

The cohort available for evaluating 12-month compliance included 105,506 patients. On average, the 12-month MPR of >80% was found in 91% of patients. Compliance was significantly less than the total mean for etidronic acid (85.7%), strontium ranelate (79.1%), and ibandronic acid (89.0%; Table 1). About 10% of all patients had an MPR of below 80%, and 5% collected more medication than needed (MPR >120%). Around 85% of the patients had a MPR between 80% and 120% (Fig. 2).

Persistence

The cohort available for evaluating persistence in starters consisted of 8,626 patients. The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 2. Mean age was 69.2 years (standard deviation, 13.8 years), 80% were women, 28% had their pharmacy in high densely populated cities, and 63% of the start prescriptions were from GPs. Most patients (95%) were receiving medication of other drug classes at the moment they started osteoporosis medication, of whom 75% had three or more medication classes prescribed and 37% had five.

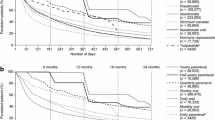

The three most frequently prescribed oral drugs for starters on osteoporosis were alendronic acid 70 mg weekly (42.9%), risedronic acid 35 mg weekly (21.1%), and the weekly combination of 70 mg alendronic acid together with vitamin D3 (11.2%). The three least frequently prescribed medications were raloxifene (0.7%), risedronic acid 5 mg (1.0%), and alendronic acid 10 mg (2.8%). After 3 months, 70% of patients were persistent and 43%, after 12 months (Fig. 3).

Compared to the mean persistence of all medications, patients using weekly one-tablet alendronic acid 70 mg combined with 2,800 IU vitamin D3 had the highest persistence after 12 months (52.7%; OR, 1.41; CI, 1.21, 1.63). Lowest persistence was found with strontium ranelate (21.9%; OR, 0.27; CI, 0.23, 0.43), daily alendronic acid 10 mg (23.2%; OR, 0.31; CI, 0.23, 0.43), cyclic etidronate (28.5%; OR, 0.42; CI, 0.32, 0.56), and raloxifene (33.3%; OR, 0.53; CI, 0.31, 0.92). Persistence was 23–40% with daily, 42–53% with weekly, and 46% with monthly bisphosphonates. One-year persistence was 52% in patients who also continued other medications compared to 43% in the total persistence population. In the multivariate analysis, 1-year persistence was higher with increasing age (OR, 1.41 to 1.64, according to age and compared to patients of 60 years and younger), medium-or lower-density urbanization (OR, 1.39 to 1.44 compared to lower urbanization as compared to very high-density urbanization of the patients), previous use of calcium and/or vitamin D (OR, 1,26; CI, 1.13, 1.39 as compared to no calcium/vitamin D), and use of multimedication at the start (OR, 9.31; CI, 7.93, 40.92 as compared to no multimedication). One-year persistence was lower in users of cardiovascular medication (OR, 0.88; CI, 0.79, 0.97 versus no use) and of glucocorticoids (OR, 0.65; CI, 0.59, 0.72 versus no use). The sensitivity and specificity used were both 65% which indicates that, although significance of individual variables was reached, there were also other (unknown) factors that influence the persistence. As can be seen in Table 2 under medication lookback period, 1,221 patients who were already treated with osteoporosis medication appeared not to influence the persistence of a new anti-osteoporosis drug. In other words, switching to another osteoporosis drug did not influence persistence.

Follow-up of stoppers

The follow-up of non-persistence 18 months after stop** the medication is shown in Fig. 4. During a further follow-up of 18 months in non-persistent patients, restart with oral osteoporosis drugs was found in 22.3%, of whom 85% restarted the original drug (18.9% of stoppers), and 15% switched to another oral osteoporosis medication (3.4% of stoppers), mostly bisphosphonates.

Discussion

This is the largest survey to date on adherence (in terms of both compliance and persistence) to the whole spectrum of oral anti-osteoporotic drugs carried out on a national scale in a routine practice setting. Analyses of this source are derived from samples of the ongoing IMS Health’s longitudinal prescription database covering ~11.5 of the 16.5 million community dwelling Dutch residents. This database differs from another Dutch database called the PHARMO Record Linkage System that contains pharmacy-dispensing data of about 2 million residents linked to a hospital discharge register [33, 34]

Compliance

On average, 91% of the patients taking oral osteoporosis medication had an MPR of ≥80%, which generally is considered as the optimal percentage for bisphosphonate treatment to be effective in preventing fractures [14]. This MPR is higher than in most other studies. This can be explained by several reasons. First, the method we used to calculate the compliance differs from other publications by including only patients with at least three prescriptions in a 1-year period, whereas in other studies, patients who had less than three prescriptions or using shorter (90 days) or even longer study periods of 2 years were included [14, 24]. Thus, our group of patients had already shown persistence during a relative long time of at least 9 months over a 12-month period, and could therefore be more compliant. Second, we included both new patients starting on osteoporosis medication and existing patients who were already treated, whereas many studies included only new patients [14, 25, 33, 35] who have lower persistence than patients already on treatment. However, as it can be seen in Table 2 under medication lookback period that 1,221 patients who were already treated with osteoporosis medication appeared not to influence the persistence of a new anti-osteoporosis drug. Third, a high compliance could be specific for the Dutch population as all prescribed osteoporosis medications including calcium and vitamin D were reimbursed. Another study on compliance in the Netherlands using other databases and 3, 6, and 12-month intervals after start of therapy showed a relatively high compliance (58%) in patients who started medication, including also non-persistent patients [34]. Recent compliance data from Sweden with comparable reimbursement also showed a high MPR with even an average of 94.6% in a large cohort of patients [36]. When reimbursement is offered, a patient’s attitude could change to obtain more frequently prescriptions from physicians and deliveries from pharmacies. Therefore, different reimbursement rules could be important in judging the MPR in different parts of the world.

Persistence

One-year persistence was low (43%), and in line with other studies from the Netherlands in which persistence of bisphosphonates was 30–52% [33] and 44% [37]. Siris and co-workers [14] compared persistence rates in different studies, mainly in bisphosphonate users, and found a 1-year persistence ranging from 24% [38] to 61% [35].

As expected and reported by others [25] described in a group of elderly women with low or moderate income the restart of osteoporosis medication. They found that of the patients who stopped therapy for 60 days, an estimated 30% restarted treatment within 6 months, and 50% within 2 years. Patients who stop medication for only 60 days are possibly more motivated to restart. However, they did not report separately restart of medication in patients who stopped medication during longer follow-up.

The strengths of the study are the extensive representative data source, nationwide coverage, and the multiple regression on non-persistence so that reliable conclusions can be drawn. We also detected factors that were related to compliance and non-compliance, and which explained 65% of the variance in persistence. The clinical implications of our findings deserve further studies to optimize adherence. It will be important in future studies to prolong the follow-up time of persistence and non-persistence, to study in prospective trials factors related to patients and doctors that contribute to compliance, and to link the pharmacy data to osteoporosis history, diagnosis, and clinical follow-up. Calculating a predictive model that delivers the types of patients having the best and the worst prognosis on persistence can be of great help for physicians. Other additional research has to be focused on a better understanding of the significantly lower persistence of patients treated with glucocorticosteroids and influence of other co-medications.

This study has also several limitations. First, the retrospective character of the design could cause bias. Moving to another address (e.g., nursing home) or death during follow-up could have biased the persistence results. Indeed, persistence for osteoporosis medication was 52% in patients who also continued other medications, compared to 43% in the total persistence population, but persistence curves of the individual osteoporosis medications were comparable between these groups (data not shown). However, since especially younger patients had lowest persistence, underestimation of persistence due to death or moving to other locations such as nursing home is unlikely. Even taking into account the more conservative number of patients with concurrent medication, the persistence was low. Second, the appropriateness of osteoporosis medication could not be analyzed because no information on fracture or bone mineral density was present in the database used. Third, no knowledge about the reason for stop** treatment is available. Such information will be of great importance in future research. Fourth, no information is available about the medical history whether the drug is taken correctly at the correct time of the day, too large doses to compensate for forgotten doses, pill dum** or stockpiling, etc. as these aspects were not part of the study design. Fifth, branded and generic alendronic acid could not be distinguished. This could be of importance since it was suggested that persistence of generic alendronic acid was poorer [49, 50]. Sixth, no data on intravenous or subcutaneous osteoporosis treatments could be analyzed because these drugs are either delivered to the patients in the hospital or by special ambulatory pharmacies. However, at the time of the study, zoledronate was only scarcely used. Seventh, it could not be taken into account if stoppers only visited the pharmacy for osteoporosis medication or also visit the pharmacy for other medications after stop**. The actual percentage of patients who stopped during the 18-month follow-up might therefore be lower. However, at the time of the investigation, intravenous bisphosphonates or subcutaneously teriparatide injections were only scarcely used, but no data were available on eventual death as the patients were anonymized.

In conclusion, compliance in non-switching and persistent patients was >90%, but more than half of the patients starting oral medication for osteoporosis were non-persistent within 1 year, and 78% of the non-persistent patients did not restart or switch to other treatment regimens during a further follow-up of 18 months. These data indicate a major failure to adequately treat patients at high risk for fractures in daily clinical practice.

References

U.S. Department of Health Services (2004) Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, USA. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/bonehealth.

Van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C (2001) Epidemiology of fractures in England. Bone 29:517–522

Tosteson AN, Burge RT, Marshall DA, Lindsay R (2008) Therapies for treatment of osteoporosis in US women: cost-effectiveness and budget impact considerations. Am J Manag Care 14:605–615

Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR (2009) Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA 301:513–521

Ryg J, Rejnmark L, Overgaard S, Brixen K, Vestergaard P (2009) Hip fracture patients at risk of second hip fracture: a nationwide population-based cohort study of 169,145 cases during 1977–2001. J Bone Miner Res 24:1299–1307

Van Geel TA, van Helden S, Geusens PP et al (2009) Clinical subsequent fractures cluster in time after first fractures. Ann Rheum Dis 68:99–102

Huntjens KM, Kosar S, van Geel TA, Geusens PP, Willems P, Kessels A, Winkens B, Brink P, van Helden S (2010) Risk of subsequent fracture and mortality within 5 years after a non-vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int (in press)

Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, Palermo L, Prineas R, Rubin SM, Scott JC, Vogt T, Wallace R, Yates AJ, LaCroix AZ (1998) Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 280:2077–2082

Solomon DH, Avorn J, Katz JN, Finkelstein JS, Arnold M, Polinski JM, Brookhart MA (2005) Compliance with osteoporosis medications. Arch Intern Med 165:2414–2419

Feldstein AC, Weycker D, Nichols GA et al (2009) Effectiveness of bisphosphonate therapy in a community setting. Bone 44:153–159

Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S et al (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1493–1501

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A et al (2008) Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 11:44–47

Seeman E, Compston J, Adachi J et al (2007) Non-compliance: the Achilles’ heel of anti-fracture efficacy. Osteoporos Int 18:711–719

Siris ES, Selby PL, Saag KG et al (2009) Impact of osteoporosis treatment adherence on fracture rates in North America and Europe. Am J Med 122:S3–S13

Sabate E (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241545992.pdf.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 353:487–497

Hiligsmann M, Rabema V, Gathon HJ, Ethgen O, Reginster JY (2010) Potential clinical and economic impact of nonadherence with osteoporosis medications. Calcif Tissue Int 86:202–210

Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ (2006) Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone 38:922–928

Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ et al (2006) Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81:1013–1022

Lekkerkerker F, Kanis JA, Alasyed N et al (2007) Adherence to treatment of osteoporosis: a need for study. Osteoporos Int 18:1311–1317

Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Yood RA, Kahler KH (2007) Consequences of poor compliance with bisphosphonates. Bone 41:882–887

Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Delzell E, Saag KG (2008) Risk of hip fracture after bisphosphonate discontinuation: implications for a drug holiday. Osteoporos Int 19:1613–1620

Penning-van Beest FJ, Erkens JA, Olson M (2008) Determinants of non-compliance with bisphosphonates in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 24:1337–1344

Imaz I, Zegarra P, Gonzalez-Enriquez J et al (2009) Poor bisphosphonate adherence for treatment of osteoporosis increases fracture risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int (in press)

Brookhart MA, Avorn J, Katz JN et al (2007) Gaps in treatment among users of osteoporosis medications: the dynamics of noncompliance. Am J Med 120:251–256

Gold DT, Alexander IM, Ettinger MP (2006) How can osteoporosis patients benefit more from their therapy? Adherence issues with bisphosphonate therapy. Ann Pharmacother 40:1143–1150

Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, Chan KA (2008) Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy 28:437–443

Buurma H, Bouvy ML, De Smet PAGM et al (2008) Prevalence and determinants of pharmacy shop** behaviour. J Clin Pharm Ther 33:17–23

Sikka R, **a F, Aubert RE (2005) Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care 11:449–457

Recker RR, Gallagher R, MacCosbe PE (2005) Effect of dosing frequency on bisphosphonate medication adherence in a large longitudinal cohort of women. Mayo Clin Proc 80:856–861

Cramer JA, Silverman S (2006) Persistence with bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis: finding the root of the problem. Am J Med 119:S12–S17

Hosmer DW, Lemesbow S (1980) Goodness of fit tests for the multiple logistic regression model. Commun Stat A10:1043–1069

Penning-van Beest FJ, Goettsch WG, Erkens JA, Herings RM (2006) Determinants of persistence with bisphosphonates: a study in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Clin Ther 28:236–242

Penning-van Beest FJ, Erkens JA, Olson M (2008) Loss of treatment benefit due to low compliance with bisphosphonate therapy. Osteoporos Int 19:511–517

Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V et al (2008) Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int 19:811–818

Landfeldt E, Borgstrom F, Robbins S et al (2010) Adherence to treatment of osteoporosis in Sweden: the Swedish Adherence Register Analysis (SARA). Osteoporos Int 21(Suppl1):S252

Van den Boogaard CHA, Breekveldt-Postma NS, Borggreve SE et al (2006) Persistent bisphosphonate use and the risk of osteoporotic fractures in clinical practice: a database analysis study. Curr Med Res Opin 22:1757–1764

McCoombs JS, Thiebaud P, McLaughlin-Miley C, Shi J (2004) Compliance with drug therapies for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. Maturitas 48:271–287

EMEA recommends changes in the product information for protelos/osseor due to the risk of severe hypersensitivity reactions (2007). http://www.ema.europa.eu/humandocs/PDFs/EPAR/protelos/PressRelease_Protelos_41745807en.pdf.

Cooper A, Drake J, Brankin E et al (2006) Treatment persistence with once-monthly ibandronate and patient support vs. once-weekly alendronate: results from the PERSIST study. Int J Clin Pract 60:896–905

Weiss TW, Henderson SC, McHorney CA, Cramer JA (2007) Persistence across weekly and monthly bisphosphonates: analysis of US retail pharmacy prescription refills. Curr Med Res Opin 23:2193–2203

Geusens PP, Lems WF, Verhaar HJ, Leusink G, Goemaere S, Zmierczack H, Compston J (2006) Review and evaluation of the Dutch guidelines for osteoporosis. J Eval Clin Pract 12:539–548

McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB (2002) Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA 288:2868–2879

Gleeson T, Iversen MD, Avorn J et al (2009) Interventions to improve adherence and persistence with osteoporosis medications: a systematic literature review. Osteoporos Int 20:2127–2134

Clowes JA, Peel NF, Eastell R (2004) The impact of monitoring on adherence and persistence with antiresorptive treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:1117–1123

Delmas PD, Vrijens B, Eastell R, Roux C, Pols HA, Ringe JD et al (2007) Effect of monitoring bone turnover markers on persistence with risedronate treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:1296–1304

Solomon DH, Gleeson T, Iversen M et al (2010) A blinded randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing to improve adherence with osteoporosis medications: design of the OPTIMA trial. Osteoporos Int 21:137–144

Rossini M, Bianchi G, Di Munno O et al (2006) Determinants of adherence to osteoporosis treatment in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 16:914–921

Ringe JD, Moller G (2009) Differences in persistence, safety and efficacy of generic and original branded once weekly bisphosphonates in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis: 1-year results of a retrospective patient chart review analysis. Rheumatol Int 30:213–221

Sheehy O, Kindundu CM, Barbeau M et al (2009) Differences in persistence among weekly different oral bisphosphonate medications. Osteoporos Int 20:1369–1376

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jasper Smit (MSc) of IMS Health BV for reviewing the manuscript, the data processing, and performing the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of interest

Amgen provided funds to IMS for data analysis. The preparation of this article was not supported by external funding. J.C. Netelenbos and P.P. Geusens have no conflict of interest, including specific financial interest and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. Buijs and Ypma are employees of IMS Health.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Netelenbos, J.C., Geusens, P.P., Ypma, G. et al. Adherence and profile of non-persistence in patients treated for osteoporosis—a large-scale, long-term retrospective study in The Netherlands. Osteoporos Int 22, 1537–1546 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1372-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1372-5